As Narendra Modi prepares to be sworn in as India’s prime minister for a third term on Sunday, the political atmosphere in New Delhi appears to be changing.

Elections that ended last week stripped Modi of his majority in parliament and forced him to turn to diverse coalition partners to stay in power. Now these other parties are enjoying something that has been unique to Modi for years: relevance and attention.

Their leaders were surrounded by television crews as they made their demands and policy suggestions to Modi. His opponents have also been given more air time, with television stations broadcasting their press conferences live, something almost unheard of in recent years.

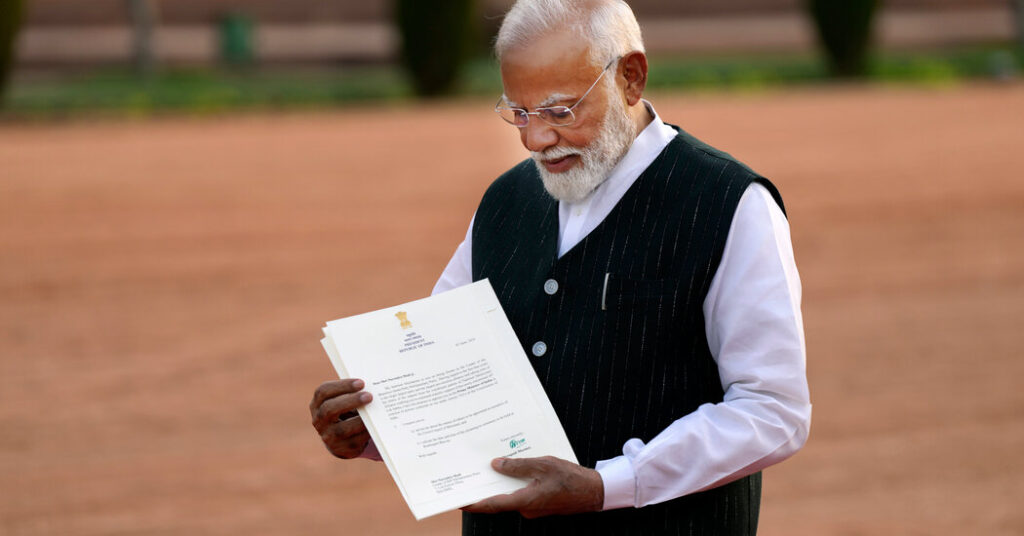

Most importantly, this change can be seen in Modi himself. At least for now, the savior’s aura is gone. He has positioned himself as the kind of humble administrator voters want.

For many, Modi’s change of attitude can only mean good things for the country’s democracy – a move toward moderation in a vastly diverse country that is being whipped into a Hindu-first position in the image of a man of behemoth.

The question is whether Mr. Modi can truly become what he has never been in more than two decades as president: a creator of consensus.

“He is a pragmatic politician who will become moderate for the survival of himself and his party,” said Ashutosh, a New Delhi-based analyst who uses only one name and is the author of a book on political issues. . “But it would be too much to expect a qualitative change in his governance style.”

A hallmark of Modi’s rule in recent years has been using the levers of power at his disposal – from the pressure of police cases to the lure of sharing power and its benefits – to defeat his opponents and sway them to his side. Analysts say the battered ruling party is likely to try this tactic to win over some lawmakers to its side to consolidate its top position.

But in the days leading up to the swearing-in, there was a noticeable change in attitude. As members of the new alliance crowded into the halls of India’s Old Parliament building on Friday to discuss forming a government, Modi stood up every time a senior ally sitting next to him stood up and began to speak. As Mr Modi accepted a garland as the alliance’s choice for prime minister, he waited for the leaders of the two main alliance partners to reach him before placing a congratulatory garland of purple orchids around his neck.

His hour-long speech contained none of his usual third-person references to himself. His tone was cautious. He focused on the alliance’s promise of “good governance” and the “dream of a developed India” and acknowledged that things will be different from those of the past decade.

The last time Mr Modi came to the Parliament building for a high-profile event, in May last year, he inaugurated the building, with some observers likening him to the entrance of a king: with a mark on his forehead as a sign of piety He holds a scepter in his hand and bare-chested Hindu monks chanting hymns walk in front and behind him.

This time, he walked right up to a constitution declaring India a secular socialist democracy, bowed before it, and raised it to his forehead.

For the first time in more than two decades in elected office, Mr. Modi finds himself in uncharted territory. So far, his BJP has enjoyed a majority as long as he has been at the helm – both at the state level as chief minister of Gujarat, and at the national level. Analysts say his high-pressure approach to politics was shaped by his experience of never being in an opposition party.

By the time he left Gujarat 13 years later, he had established such firm control and defeated the opposition that the state had effectively become a one-party state. In 2014, his Bharatiya Janata Party won its first national victory by winning a majority in parliament, ending decades of coalition rule in India when no party was able to muster the 272 seats needed for a parliamentary majority. seats. In 2019, he was re-elected with a larger majority.

Modi’s immense power has helped him quickly implement his right-wing party’s decades-old agenda, including building a lavish Hindu temple on a long-controversial site that once housed a mosque and revoking the special status long enjoyed by Hindus. most areas.

A hallmark of his governance has been a disregard for parliamentary procedures and legislative debate. His surprise overnight demonetization in 2016 – rendering India’s currency invalid in an effort to combat corruption – plunged the country into chaos and dealt a blow to an economy still driven by cash. Likewise, the rush to enact laws aimed at reforming agricultural markets led to a year of protests in Delhi, forcing Modi to retreat.

Before the election results were announced, Modi’s party had predicted that his alliance would win 400 of the 543 seats in India’s parliament. Modi said the opposition would have to “sit in the audience”. His administration officials have made it clear that in his new term he will seek to implement the only major remaining item on the party’s agenda: legislating a “Uniform Civil Code” in the diverse country to replace the religiously diverse laws that currently govern it. Different laws. His party leaders say Modi is the leader not only for this term but also for the next elections in 2029, when he will turn 78.

“He has been trying to change the country,” Sudesh Verma, a Bharatiya Janata Party official who wrote a book about Modi’s rise, said in an interview before the election results. “I expect him to work into his 90s like Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew.

But Modi’s traditional approach will struggle under a coalition government.

The two main coalition parties that helped him secure the lowest parliamentary seats to form the government are both secular parties, in stark contrast to Modi’s Hindu nationalist ideology.

N. Chandrababu Naidu, whose party holds 16 seats, has been harshly critical of Modi in the past over his treatment of Muslim minorities. He also publicly criticized Modi for using central investigative agencies to target his opponents and taking “measures that subvert all democratic institutions.”

Neerja Chowdhury, a Delhi-based political analyst and author of the 2023 book “How the Prime Minister Makes Decisions,” said: “If allies don’t act, contentious ideological issues such as the Uniform Civil Code will enacted, may be set aside.

Mr Modi’s popular image is built on two powerful pillars. He was a champion of economic development with an inspiring biography that told the story of his rise from humble caste and relative poverty. He is also a lifelong Hindu nationalist who has been a fighter for decades in a movement to transform India’s secular and pluralist state into an openly Hindu-first state.

At the height of his power, Hindu nationalist forces became increasingly dominant. Analysts say the recent rebuke from voters could be a lucky break for the country: prompting Modi to tap into his development advocate side and focus on a legacy of economic transformation that can improve the lives of all Indians.

“To run a government, majority is necessary. But to run a country, consensus is necessary,” Mr. Modi said in his speech. “People want us to do better than we did before.”

Suhasini Raj Contribution report