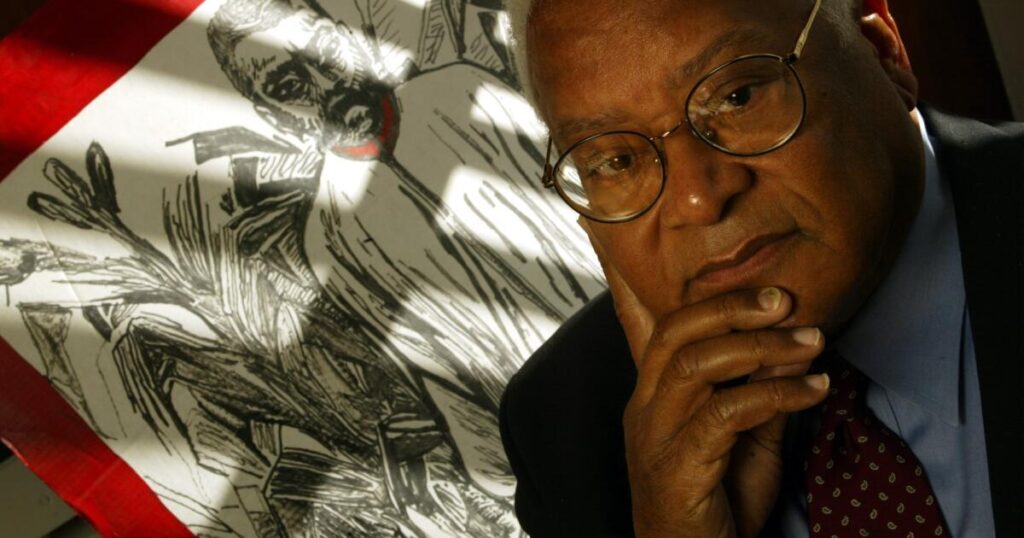

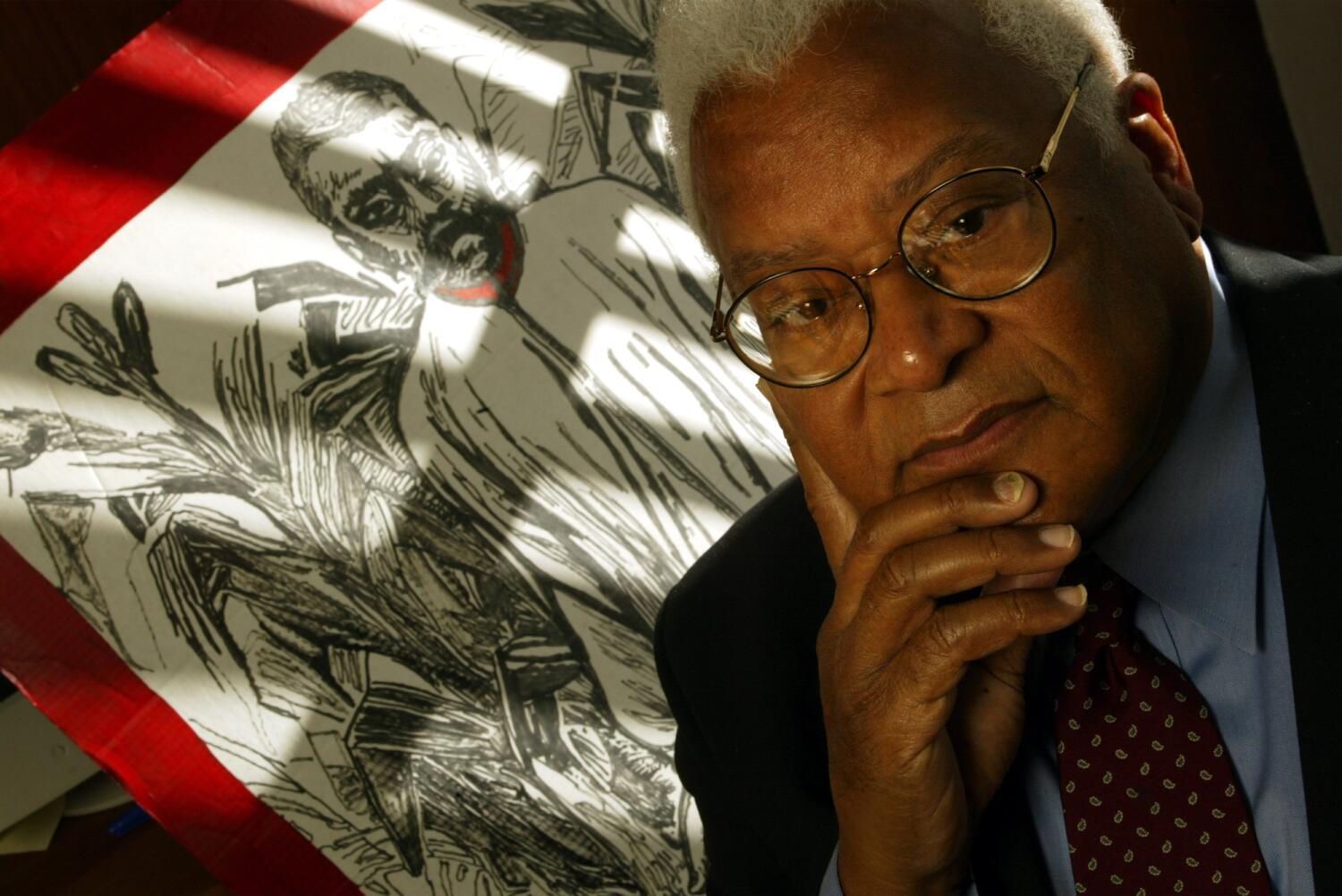

James M. Lawson Jr., the Methodist minister who became a teacher of the civil rights movement, trained hundreds of young protesters in nonviolent tactics and made Nashville lunch counter sit-ins a 1960s phenomenon, has died A model for the fight against racial injustice. He is 95 years old.

Lawson, who spent decades as a pastor, labor organizer and college professor, was visiting a Los Angeles family on Sunday, his son J. Morris Lawson III told The Washington Post. He died of cardiac arrest on the way to the hospital. He is 95 years old.

Recruited by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Lawson organized and led weekly nonviolent action seminars in Nashville and other movement hot spots. These workshops trained many future leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, including the late Congressman John Lewis.

“I really feel…he’s a God-send,” Lewis once said of Lawson. “There was a mystique, a divine feeling about his manner… This man was a born teacher in the truest sense.

Lawson, whom King called “a leading theorist of nonviolence,” studied Gandhi’s philosophy in India before joining the struggle in the South. He led seminars throughout the region and became a traveling problem solver for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In 1968, he invited King to speak to striking sanitation workers in Memphis, where the charismatic preacher met his own demise, where he was assassinated.

Lawson worked with various civil rights organizations in the South until 1974, when he moved to Los Angeles to become pastor of Holman United Methodist Church. He led the church for 25 years. He retired in 1999 but remains an activist for peace and social justice.

James M. Lawson Jr., the son of a proud black preacher, didn’t always practice nonviolence. As a young boy in Ohio in the 1930s, he slapped a white kid for yelling a racial slur at him.

Fortunately, Lawson was unaffected—until he got home.

“Jimmy,” he said when he told his mother what he had done, “what’s the good of it? There has to be a better way.

She was busy in the kitchen, not looking at him as she scolded him, but the words resonated. Lawson later recalled that he felt like his world had “kind of stopped.” “Somewhere deep inside me, I heard myself saying, ‘I’m going to find a better way.'”

His explorations took him to India, where he studied Mohandas K. Gandhi’s ideas on nonviolent resistance. After returning to the United States, he applied what he learned to the civil rights movement, combining Gandhian principles with biblical insights to become what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called “the leading theorist of nonviolence” of his era.

A key figure in some of the movement’s most important movements, including the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins, the first Freedom Rides and the social justice fights he led as pastor of Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles.

King’s 1955 Montgomery bus boycott demonstrated the power of nonviolent protest. But it was Lawson who provided the disciplined guidance to the young protesters who took the civil rights movement into its next phase. He not only taught them the noble principles of passive resistance but also basic tactics, including how to withstand taunts and physical attacks, avoid violating loitering laws, historian Taylor Branch writes, and “even how to dress” for sit-ins, which meant Wear “stockings” for ladies, high heels, and gentlemen, coats and ties.

His nonviolence seminars trained many of the leaders who fueled the movement in the 1960s, including Lewis, who was one of the organizers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

“I could not have asked for a better teacher than Jim Lawson,” Lewis wrote in his 1999 memoir. “It is not difficult to seek forgiveness. Jim Lawson tells us that this is the essence of a nonviolent way of life.

James Morris Lawson, Jr. was born on September 22, 1928, in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, and grew up in Massillon, Ohio. He carried a gun while traveling in the South. Lawson was the sixth of nine children, and his father “believed that I should fight to protect myself,” he recalled in a 2000 interview with National Public Radio.

He was in high school in the 1940s when he staged his first sit-in, targeting a Massillon restaurant that refused to serve blacks. The owner served him but told him never to come back.

After high school, he attended Baldwin Wallace College, a Methodist college in Berea, Ohio, and joined the Pacifist Reconciliation Fellowship. When he was drafted into the Army during the Korean War, he refused to enlist and was sentenced to 14 months in prison.

In 1953, Lawson participated in a Methodist mission to India and devoted himself to the study of Gandhian nonviolence. In late 1955, he also read a newspaper account in India about the Montgomery bus boycott. “I think it was an answer to a prayer,” Lawson told The Times in a 1984 interview about the protests led by King. “My reaction was to start cheering.”

In 1956, he returned to the United States and attended Oberlin College’s Graduate School of Theology, where he met King in 1957.

In 1958, Lawson moved to Nashville and enrolled in the theology program at Vanderbilt University. He also joined the Nashville Christian Leadership Council and began conducting nonviolence seminars.

Lawson relied heavily on role-playing, often asking students to taunt others with racial slurs to help them learn self-restraint. He showed students how to conduct an orderly sit-in by taking turns filling seats at the lunch counter. He also showed them ways to reduce damage by maintaining eye contact with their attackers and using their bodies to help diffuse the blows that were sure to come.

In November 1959, Lawson’s students held three meditation exercises. “We just did it quietly,” he told The Times in 2014, without any media coverage.

The Greensboro, North Carolina, student began conducting a series of impromptu sit-ins on February 1, 1960, and after receiving national media attention, he cut his training short. The People’s “Nonviolent Army” A powerful force from Fisk University and other local universities sprang into action, occupying three lunch counters in downtown Nashville. Over the next three months, more venues were targeted, including bus terminals and major department stores.

“Obviously we have a very disciplined campaign … focused on students,” Lawson said.

Lawson was expelled from Vanderbilt University when 81 students were attacked by a group of white men and subsequently arrested. Faculty members resigned in protest, making headlines across the country.

The turning point came when the home of an attorney for jailed protesters was bombed, sparking a massive march to Nashville City Hall and a boycott of white-owned businesses. In May 1960, three weeks after the mayor called on white citizens to end discrimination, Nashville lunch counters began serving blacks, and the sit-in movement soon spread to dozens of other Southern cities.

Lawson believed that sit-ins were more effective than litigation, and in a 1960 speech at Shaw University in North Carolina, he criticized sit-ins as “a traditional, half-assed effort by the middle class” to address serious social injustices.

Longtime activist Julian Bond recalled in Voices of Liberty, an oral history of the movement, that Lawson sounded “like a bad younger brother, urging King to do more and become more radical” and “disrespectful of Nonviolence has more ambitious ideas”. can do. “

The day after Lawson’s speech, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was formed based on a statement of purpose drafted by Lawson. Originally led by future Washington Mayor Marion Barry, the SNCC helped promote major civil rights movements, including voter registration projects and the 1961 Freedom Rides.

When the first Freedom Rides were derailed by mob violence, a small group of Lawson-trained Nashville students completed a dangerous bus trip from Montgomery, Alabama, to Jackson, Mississippi. Other Mississippi Freedom Riders were arrested along with them. At Lawson’s urging, they refused bail, prompting hundreds of other students to join the movement against the interstate travel quarantine.

In 1962, Lawson became pastor of Centenary United Methodist Church in Memphis. In 1974, he traveled to Los Angeles and was hired to lead Holman United Methodist Church.

Over the next 25 years, until his retirement in 1999, he remained a prominent activist. He was co-chairman of a gathering of 200 South Los Angeles pastors protesting the 1979 shooting death of Yura Love by Los Angeles police and led the Los Angeles chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was arrested several times during protests, including rallies against U.S. military aid to El Salvador in the late 1980s. In 2000, he risked being tried by the church for blessing a lesbian wedding.

After Lewis’ death in 2020, Lawson, 91, joined three former U.S. presidents in paying tribute to the congressman at a memorial service at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. In an eloquent eulogy, concluded with poetry by Czeslaw Milosz and Langston Hughes, he exhorted Americans to “practice the politics of the preamble to the Constitution” as “the only way to honor Lewis’s life” “.

He said he did not regret his fateful invitation to King in 1968 to address striking sanitation workers in Memphis. dream of equality, adding, “I may not get there with you.”

“Martin expected he was going to die,” Lawson told The Times in 2004. “I don’t know if he specifically expected this to happen, but he knew from Montgomery that he could be shot down at any time.”

Lawson wondered what kind of person could commit such a crime, and he began visiting convicted murderer James Earl Ray in prison. He, like members of the King family, came to believe Ray was innocent and unsuccessfully pushed for a new trial. When Ray decided to marry a sketch artist who had covered his arraignment, he asked Lawson to perform the committal ceremony.

“It wasn’t just that I doubted his guilt; it was that I doubted his guilt. It was much more than that,” Lawson told historian John Egerton years later. “I know that if Martin were alive and in my position, he would have married them even if he knew Ray was guilty. As one of my sons said to me: ‘If you believe all the stuff you keep preaching, you It will be done. “

“Of course, he’s right.”

Lawson is survived by his wife, Dorothy Wood, and two sons, J. Morris Lawson III and John Lawson. one brother, Philip; and three grandchildren. His son, C. Seth Lawson, died in 2019.

Wu is a former staff writer for The Times.