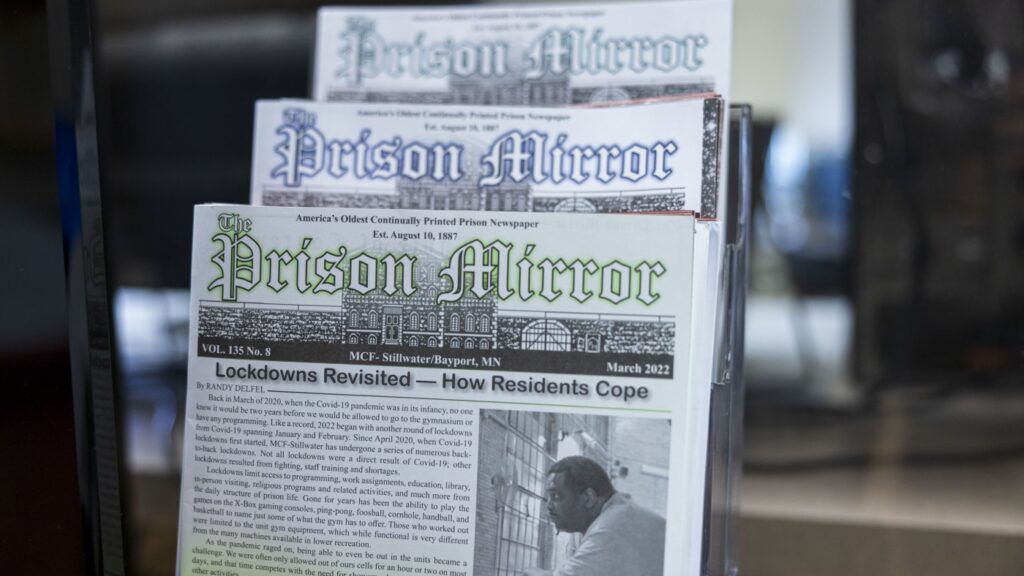

previous issues prison mirror, The book has been published since 1887 and is now on display at the Stillwater Correctional Facility in Minnesota.

Kerem Yücel/MPR News

hide title

Switch title

Kerem Yücel/MPR News

At a state prison near Stillwater, Minnesota, Richard Adams and Paul Gordon hid in a corner of a computer lab, past armed guards and wing after wing of cells, working on a heated Discuss grammar.

Both are employees of the company prison mirroris a newspaper produced by and for those incarcerated at Stillwater Correctional Facility in Minnesota. Gordon wrote a profile about a prison art teacher. He read it aloud to Adams.

“I was curious if there was a certain style or thing that he liked to draw. “When I have time, I like Bob Ross and he draws on the TPT channel,” Gordon said, citing the Twin Cities’ PBS channel. Adams leaned forward, a puzzled expression on his face, and asked him to repeat the statement.

“Is that what he said?” Adams asked. “It sounds like you’re saying you like the guy on the TPT channel.” He suggested Gordon add an attribution message to the quote, such as “he said” or “he answered.”

Conversations like this have been happening in this prison for more than a century. this prison mirror It is one of the oldest prison newspapers in the United States, having been published since 1887. is growing.

Staff consisting of Richard Adams (left), Paul Gordon (center); and Patrick Bonga prison mirror at Stillwater Correctional Facility in Minnesota. These people said they were limited in what they could write about, but they still found meaning in their work.

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

hide title

Switch title

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

“In general, we’ve definitely seen a growth and a lot of interest in starting publications and even podcasts. So that’s really exciting,” said Yukari Kane, CEO of the Prison Journalism Project.

Thirty years ago, she said, there were an estimated six prison newspapers. Today, there are more than two dozen. That doesn’t take into account the hundreds of incarcerated writers who submit work to outside publications, such as The Marshall Project’s Life Inside series.

Kane said this type of work can provide a window into the reality of prison conditions that prison administrators don’t necessarily provide for free.

“People in prison see and experience a lot of information every day. Some reporting can only be done from the inside,” she said.

Even if a newspaper’s circulation doesn’t reach far beyond the prison yard, it can provide its authors with a sense of empowerment.

“Having a newspaper is good for everyone. It informs people. It gives you a voice,” Gordon said. “I like a saying: You can either be an agent of fate or a victim of fate.”

Senior Editor Patrick Bonga is working on the latest issue of prison mirror at Stillwater Prison.

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

hide title

Switch title

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

Stillwater inmates write book reviews, legal explanations, and summaries of local, national, and international events for a monthly magazine. One man recently submitted an essay about homesickness. Another wrote an editorial criticizing the lockdown. There are only three people on staff who have to apply for these unpaid jobs, and they are in high demand.

The job requires a lot of reading and research about what’s happening around the world and in prisons, Adams said. There are challenges. For example, they do not have internet and therefore must rely on print media and articles printed by prison staff.

“Technically, they do have a free press, but they themselves are not free.”

Prisons must also approve everything published by newspapers. These people say this can limit what they write about, especially if they want to cover the harsher aspects of life.

Gordon said: “It’s understandable in the sense that I’m restricted and they won’t let me run all the types of crazy things about water or lockdowns or being restricted or anything like that. “

Last fall, about 100 Stillwater inmates refused to return to their cells. Gordon said the disobedience was their way of protesting the extreme heat, poor water quality and staffing shortages that he said often led to lockdowns. He plans to write about the matter but said he has faced retaliation in the past for sending reports to outside publications.

“I was more proactive in my writing then, and it was a learning experience for me,” he said.

Paul Gordon, who has been in prison for nearly 20 years, said he wanted to “write something important”.

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

hide title

Switch title

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

Brian Nan-Sonnenstein, senior editor at the Prison Policy Initiative, said it’s common for people to be punished for doing journalism behind bars.

“You could lose what’s called good time points, which are essentially time off your sentence based on good behavior. You could go to solitary confinement. Your privileges could be revoked,” he said.

“Technically, they do have a free press, but they are not free themselves,” said Kane of the Prison Journalism Project. “So they do face the consequences of what they’ve done and may even face consequences.”

Furthermore, while the ability to write freely varies greatly from prison to prison, having everything approved by prison administration could undermine the entire journalism enterprise, Southern Sonnenstein said.

“Incarcerated newsrooms are not necessarily fully occupied carceral institutions, but we do have to recognize the constraints they are subject to, especially when we compare them to free world journalism,” he said.

Marty Hawthorne, a prison instructor who oversees the newspaper, said he believed inmates “had the right to do what they were doing” in publishing the newspaper.

Kerem Yusel | MPR News

hide title

Switch title

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

Marty Hawthorne works and oversees the Stillwater Prison Prison mirror.

“They have a lot of freedom. My philosophy is: This is their newspaper. This is not my newspaper,” he said. “I believe they have the right to do what they’re doing.”

He said if these people planned to publish something critical, he would make sure anyone they wrote about had a chance to respond. But he said he also pushed back when leadership tried to censor stories he believed were fair.

“Because that’s my job,” he said. “They are incarcerated people, right? They have no power or authority. Someone has to speak for them in these places.

Gordon had been working at the paper for several months, nearly 20 years after serving a life sentence for murder.

“I believe my job is just to take a position and let people draw their own conclusions,” he said. “I hope to write something important, and by writing, I hope to leave a very different footprint than the one I’ve already left on the world.”

Posing in his prison cell, Patrick Bonga said working in journalism changed the way he thought about the world and helped him fight prejudice.

Kerem Yusel | MPR News

hide title

Switch title

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

Patrick Bonga, the paper’s senior editor, said covering all aspects of the story has changed his view of the world. He has been in and out of prison many times. Now under attack, he said the paper is helping to break the cycle.

“For the first 40 years of my life, any other perspective other than my own didn’t matter. But now that I have to stay objective and put together stories that are not one-sided, I’m now starting to practice a lot of disapproval in my own life The fight against prejudice. This is a big deal,” he said.

For Gordon, publishing the paper was more than journalism. It’s about reaching a turning point.

“When we first go to prison, it’s a journey of figuring out what to do this time. We come here angry at the world because life isn’t going well. We try to figure it out day after day and Find a moment where if we make that decision, everything will work out,” he said. “Then we get angry at the people around us because no one is helping us in that moment. It’s a journey that ultimately allows us to take responsibility for our actions and ultimately be able to grow.

Adams said he wanted to keep his story positive.

“I don’t want to bring a negative light on the newspaper because we all know what’s wrong. Let’s bring more positive and right things,” he said.

He set up a suggestion box in his cell to allow other inmates to comment on what they wanted to read. He also wants to start an advice column. He’s a father, and he thinks other men will have questions about how to be a good father, even if their relationship with their children is primarily over the phone.

Richard Adams hopes to write positive stories for the paper that will give other inmates the tools they need to succeed after they get out of prison.

Kerem Youssel | MPR News

hide title

Switch title

Kerem Yusel | MPR News

Now, he’s writing about side hustles men can do after prison to make some extra money — like driving for Uber and DoorDash, or selling flowers.

“While you’re here, you have a choice, you can change, or you can go back there and do the same things that got you here. You can go back there and at least try to make a change,” he said.

After all, most people in prison get out and return to their communities. Adams wants to give them hope and give them the tools to start over when they get the chance.