The logic of the streaming age slowly creeps into rap fans’ favorite pastime

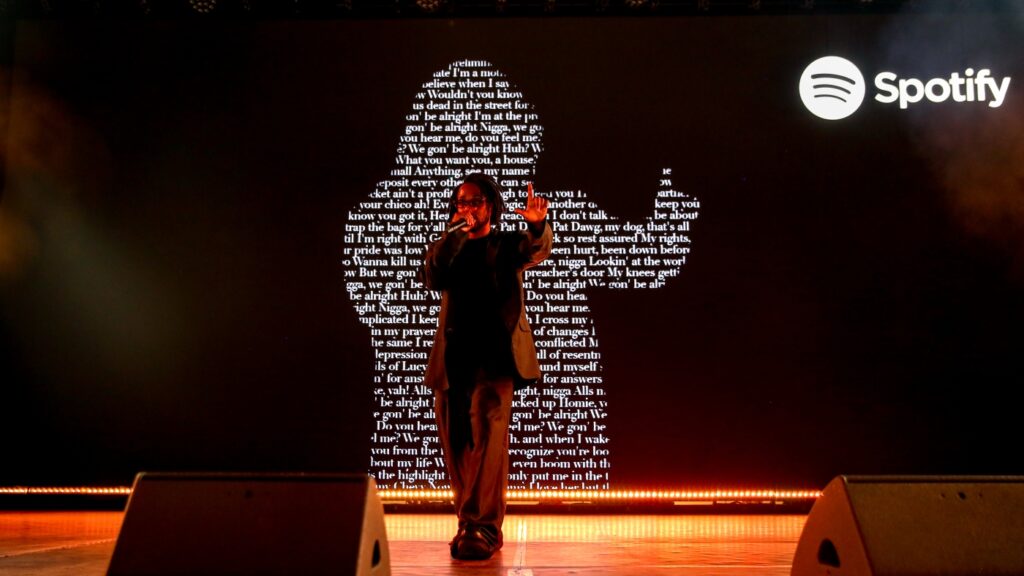

Kendrick Lamar performs at a Spotify event during the Cannes Lions Media Festival in Cannes, France in June 2022.

Dave Bennett/Getty Images (Spotify)/Getty Images Europe

hide title

Switch title

Dave Bennett/Getty Images (Spotify)/Getty Images Europe

If you listen to rap music, or watch professional basketball, you know that one of the core experiences associated with both is hatred. Of course, this isn’t meant to be malicious – more of a mean thing. Sometimes a player just annoys you for this reason. Sometimes the fan base can be annoying and you enjoy seeing them suffer. Sometimes the hype gets out of hand and needs to be corrected. Much of the discussion in both fields is devoted to hate, and since this discussion mostly takes place online, we’re almost always in the middle of it. Doomscrolling long enough will inevitably land me in a conversation I don’t actually want to be a part of but can’t look away; the annoying cycle of reading, listening, and watching can inspire a specific kind of madness in which The space of the screen feels like the entire world. When consumed by the troubles that arise from hatred, there may be a moment when irrational, violent reactions may feel like the only option.

Recently, just before Game 1 of the NBA Finals between the Mavericks and Celtics, I stumbled upon a post on X from Spotify’s premier hip-hop playlist, RapCaviar, and this familiar, searing feeling swept over me Got me. I don’t use Spotify, and my relationship with what was once called the most influential playlist in music has always been cautious because, in my opinion, it never really reflected the breadth of the genre it was trying to encapsulate. I was already disturbed to receive this article from an account I didn’t follow, but I was even more shocked by its content: an NBA-like power ranking chart with the faces of various hip-hop stars, arranged in the grid. The ranking is the streaming platform’s rap ranking, and if you’ve been paying casual attention to music over the past few months, predictably, the number one spot is Kendrick Lamar. The next top five are Future & Metro Boomin, GloRilla, Gunna and sexyy red. (A photo of a goat, currently Kanye West’s official profile picture on the app, takes his place at No. 10.) “Who is your MVP this year?” the caption asked. I should keep scrolling, or better yet, put down the phone. But I find myself hesitant about the question, not because I’m interested in the specifics of this type of competition, but because of who’s asking the question.

I looked for some background. The event is part of an ongoing RapCaviar series called “All-RapCaviar Teams,” modeled after professional basketball’s end-of-season honors. RapCaviar’s edition is comprised of “the 15 rappers who have had the biggest impact on the flagship playlist (and other hip-hop-centric Spotify playlists) over the past 12 months,” a press release from the 2023 selection process explains. Fans then have the opportunity to vote for their MVP via social media. “As the leading destination for hip-hop, conversation and culture, we’re excited to unite the best rappers in the game with their biggest fans through this unique social-first experience,” the statement concluded. Stay tuned to find out Who will step up and lead the hip-hop trend in the coming year. True to the black-box reputation of the streaming economy, I can’t find any breakdown in methodology, nor the key think tanks responsible for shaping the presentation. I can’t even find a clear explanation as to why the project exists, other than a quote from creative director Carl Chery in 2022 about encouraging “a little friendly debate online.” This is a ranking based on numbers, but with no work on display and no personality on display, it’s hard to say what the numbers mean. So, what’s the point?

See, I hate it. I get it. By itself, this kind of thing is harmless. You see it online every day, and it’s a key part of the melee, and that’s engagement; its variations spread in every direction and can be satisfying and insightful, transcending the moment and the echo chambers of social media . Think of the energetic comings and goings in Chris Rock’s living room. top fiveor MTV’s now-defunct annual list of the hottest MCs in the game, or even Shea Serrano’s rap yearbook, there is no disagreement among enthusiasts in every choice. It has its value in practice. But I’m not wrong either, it feels weird when an entity like Spotify enters the chat. The chief benefit of our words, however trivial, is that it our, a reflection of personal taste and investment. When a company inserts itself into this mix, it can only hope to speak in the monotonous voice of the bottom line, out of a featureless void.

To be fair, hip-hop has long been compared to the meritocracy of basketball. Rappers have always referred to the music industry as “the game,” and many have turned professional sports’ “GOAT” rhetoric into a template for success in their fields. In “Just Rhymin’ with Biz,” Big Daddy Kane raps, “If rap were a game, I’d be MIC’s MVP/Most Valuable Poet.” Ten years later, The Game himself would do it on Hate It or Love “It” goes a step further, declaring that rapping is actually a game designed to help him escape his loser status. When budding rap star Biggie calls the streets a temporary stop where the only way to escape is to throw a rocker or perform a wicked jump shot, he says competition is the common denominator. As recently as 2019, 2Chainz named an album Rap or go to the league. To embrace ball is to embrace skill as a doorway from hardship to glory, and Hustler’s honing of skills for prime time is understandable for a class of performers who view their moves as deft and masculine. But even at its most braggadocious, this mentality has always been more focused on clutch performances and clever strategies than pure commercial success. RapCaviar’s 2023 MVP Drake cites Allen Iverson-Michael Jordan crossover on 2010’s ‘Thank Me Now’ to clarify showable ability and the correlation between taking chances: “That’s when your idols become your rivals/You make friends with them. Mike, but for your survival, you must AI him.”

Game, 50 Cent – Hate It or Love It (Official Music Video)

Youtube

This should be obvious, but it’s one thing for rappers to use this analogy as a means of self-expression, and it’s quite another for the most powerful companies in music to try to define those parameters. The value of this exercise is that hip-hop artists and the diehards who follow them will fight ad nauseam over who’s on top. Powerless It’s certain in every sense of the word. There is zero chance of reaching consensus in a barbershop rap debate. This is where MVP discussions become a purposeless and fun pursuit, driven by the talents, gifts, and skills of the participants, which is exactly what rap’s founders intended. That’s why it’s so perverse for a streamer to use this kind of dialogue to promote their own algorithmic capabilities, if you just take a moment to think about it. This is a betrayal of this frivolous spirit, an attempt to use the “certainty” of data to justify choices.

Ironically, Drake has since become a beacon of that certainty: Globally, he is Spotify’s most-streamed male artist of all time. In recent years, the language of Drake’s trash talk has aligned with that of Stan Revolt, where streaming-fueled sales figures are used as the most important determinant of aesthetic value and cultural significance. His status as the 2023 MVP embodies that outlook, tying streaming success to rap greatness. Meanwhile, Kendrick is now atop the All-RapCaviar power rankings due to his Drake diss track doing well on Spotify, and on an unofficial level, he could be many people’s pick for rap MVP this year. But he didn’t make all that money playing streaming games, and he certainly didn’t replace Drake because of his “impact on Spotify’s hip-hop-centric playlists”—he did it through artificial intelligence. . His crossovers were equally devastating, seen around the world, mowing down a legend.

While it’s just a silly social media ploy, the launch of All-RapCaviar feels like part of a more insidious trend: the gamification of rap, the shift in focus from bars to metrics, and, more broadly, the streaming giant’s take on business and Culture makes no difference in the field of music. Their Words Are Too Definitive – “The leading destination for hip-hop, conversation and culture” featuring the “best” rappers to find which one will “lead” the genre – for a guide guided by anonymous machine data thing. Defining the music in these business terms only helps transform hip-hop into a spectator sport that sells tickets. Not surprisingly, the most toxic discourse circles in rap are very similar to those of critics in sports media. Hip-hop is a sport in the sense that competition can drive creative breakthroughs, but when you start really looking at art as a numbers game, it becomes less worth playing.

We know that streamers want to be both business and culture, business infrastructure and standard setters. Check out the Apple Music 100 for more recent examples of bolder attempts at taste shaping, or look at Spotify’s own Classics series, which lists the greatest hip-hop and R&B songs of the streaming era. The problem is that any attempt to edit music on these platforms from the top down is inevitably a marketing exercise—a way to get the numbers up, reaffirm the artist’s relevance, and validate the platform through agents necessity. Corporations cannot lead culture, especially one that is widely criticized for harming artists’ livelihoods. Even more dangerously, such moves are gaining momentum at a time when the editorial structures once responsible for such work at newspapers, magazines, alternative weeklies and regional broadcasters continue to collapse. Because of their convenience and connectivity, these mega-enterprises are optimized for an artistic vision where everything—the music, the conversation around it, the artists themselves—is just content.

If there’s any consolation, it’s that even the most official statistics can never be the beginning or end of a conversation, but only the baseline for more inevitable squabbles. I believe in my heart that Kobe Bryant should win at least one Steve Nash MVP. My brother recently argued to my dad that current Boston Celtics guard Jaylen Brown is a better player than Dr. J, the two-time ABA MVP and 1981 NBA MVP. Likewise, someone somewhere is lobbying for Chief Keef, Rapsody, ScHoolboy Q, or Tierra Whack, rappers whose playlist influence is too small for Spotify to consider them the greatest in the game. Maybe one day the All-RapCaviar team will become a very important televised ceremony. Maybe they’ll disappear and be just another blip in the never-ending push to get engaged. In either case, the real conversation always happens elsewhere, well beyond the confines of the data.