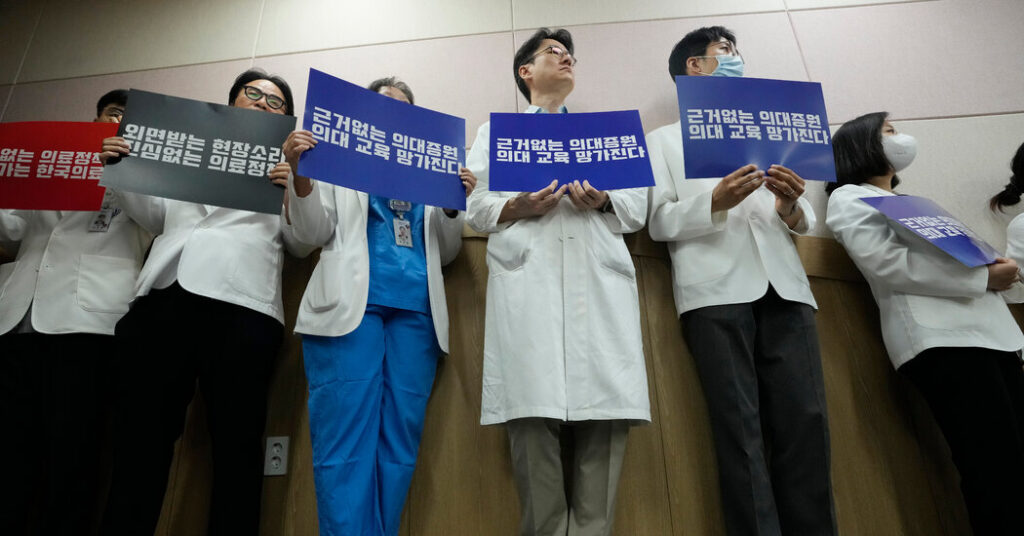

Doctors at medical facilities across South Korea went on a one-day strike on Tuesday, a dramatic expansion of months-long protests against government health care policies that began in February when residents and interns at major hospitals stopped working. .

The doctors participating in the one-day strike belong to the Korean Medical Association, the country’s largest doctors’ organization, with approximately 140,000 members. The group said it was unclear how many people were involved, but its members recently voted three to one in favor of collective action.

South Korean President Yoon Seok-yeol called the latest strike “very disappointing and unfortunate” during a televised cabinet meeting on Tuesday morning. A day earlier, hundreds of medical professors at Seoul National University Hospital and other major institutions began an indefinite layoff.

“My liver is not good, so I came for an ultrasound test,” Yang Myoung-joo, an 84-year-old patient at Seoul National University Hospital, said on Tuesday. She said her appointment had been canceled and no new date was provided. “Doctors deal with people’s lives. Is a strike the right thing to do?

The controversy began in January, when Mr. Yin’s government announced new health care policies that included plans to significantly expand medical school enrollment. Doctors say the plan was drafted without consulting them and will not solve the health care system’s problems. But the government says South Korea urgently needs more doctors because it has fewer doctors per capita than in most developed countries.

Neither side has made much concessions. In May, the government set medical school enrollment at 4,570 students for the 2025 academic year, an increase of about 1,500 students — fewer than the 2,000 originally proposed, but still a significant increase. The announcement appears to have triggered the latest industrial action.

Lim Hyun-taek, president of the Korean Medical Association, said during a meeting with the organization’s leaders last week that “the government has still not admitted its wrongdoing and is still pursuing wrong policies and condemning the medical community.” Dr. Lim said Yoon His administration has long ignored the hard hours and low pay of doctors in pediatrics and other vital fields.

Although the health care system has been strained since February, it has not collapsed. To fill service gaps, the government deployed military doctors and asked nurses to take on some tasks normally performed by doctors. The government said this week it was operating hundreds of emergency rooms across the country and making contingency plans in case the dispute continued.

South Korean Prime Minister Han Deok-soo said in a recent statement that the doctors’ strike “has left a huge scar on society and undermined the trust built over decades” between doctors and patients.

Many members of the public were also critical of the strike, with some accusing doctors of trying to protect their elite status by keeping numbers low. The backlash has spread to the medical industry itself, with union hospital workers rallying in Seoul last week to urge doctors to call off a one-day strike on Tuesday. “Delays in treatments and surgeries are distressing for patients and hugely distressing for hospital staff, who are subjected to endless inquiries and complaints,” a union statement said.

Kang Hee-kyung, a pediatrician at Seoul National University Hospital who leads a committee of retired medical professors, said at a recent press conference that the action was a last resort and stressed that patients who need immediate care will receive it. treat. “We apologize to critical care and rare disease patients,” he said.

The government has tried to persuade interns and residents who struck in February to return to work, abandoning previous threats to revoke their licenses and promising impunity for those who return. But only 7.5% of some 14,000 interns and residents at 211 teaching hospitals went to work last week, according to health ministry data.

Protest leaders say the protests will only end if the government cancels plans to expand the medical school. But a Department of Health spokesman said the 2025 enrollment quota was non-negotiable. The patient becomes increasingly irritated and loses hope of a quick solution to the problem.

“This may take several months,” Ms. Yang said. “There’s nothing I can do as a patient.”