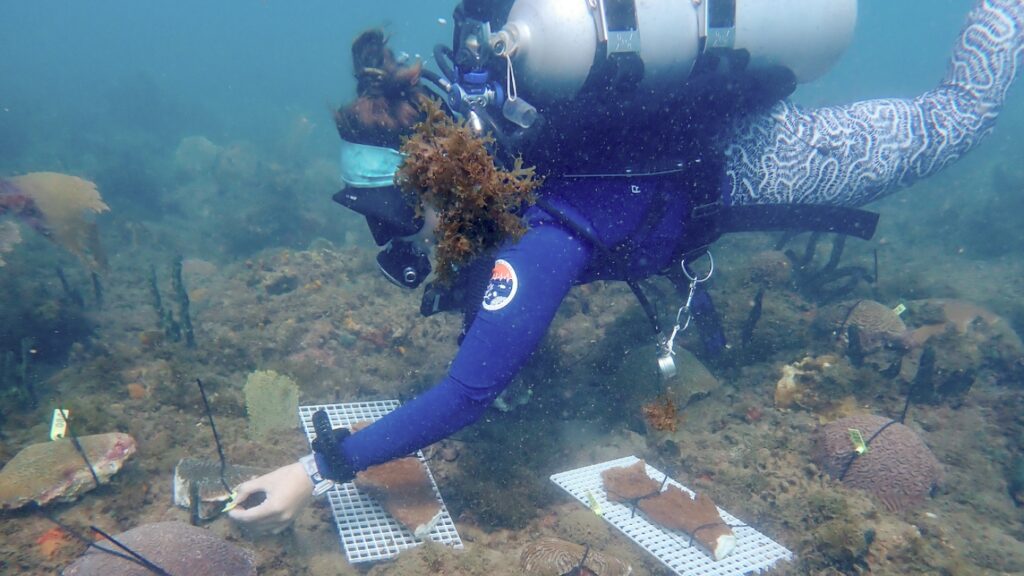

Cailyn Joseph, a doctoral student in Andrew Baker’s lab, sorted the brains and Acropora corals in Honduras before traveling to Miami.

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

hide title

Switch title

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

MIAMI — Off the northern coast of Honduras, dense colonies of endangered Acropora corals have mysteriously resisted ocean warming caused by climate change, covering the reef with healthy, cocoa-brown colonies that extend out of the water like antlers.

The reef near the colonial town of Terra has more than three times as many live corals as anywhere else in the Caribbean.

Now scientists at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School hope to unlock the secret and cross the sturdier corals with Florida antlers to buy more time for reefs that are shrinking from rising ocean temperatures and disease.

Brain coral (left) and endangered staghorn coral on a reef near Stella, Honduras, grow in water with temperatures hovering around 88 degrees.

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

hide title

Switch title

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

“Typically we associate coral reefs with clear water and pleasant temperatures. These are rough, tough reefs,” said Andrew Baker, a coral biologist at Rosenstiel who led the study. “There’s a lot of Acropora here and a lot of other corals. It’s a bit of a mystery why the corals do so well.

In Florida and around the world, the ocean absorbs more than 90 percent of the additional heat trapped by greenhouse gases. Extra heat is destroying coral reefs. Last year’s record high temperatures triggered a global bleaching event, the second in a decade. In Florida last summer, a scorching heat wave caused corals to spit out life-sustaining algae and bleach, turning them a ghostly white.

Rising global ocean temperatures are endangering coral reefs, which can bleach when the water stays warm for too long. But near Tela on the northern coast of Honduras, coral thrives in hotter, turbid water. Scientists hope to breed them with Florida corals to produce more resilient offspring.

Manuel Chinchilla/iStockphoto/Getty Images

hide title

Switch title

Manuel Chinchilla/iStockphoto/Getty Images

With water around Florida once again hitting record highs this summer, Baker and a group of students flew to Honduras in May to find what he hoped would be the parents of new, more resilient Florida corals.

One morning in June, at 4 a.m., they got up during the day and went to the reef to collect coral. After packing the coral in wet paper towels and sealing it with bubble wrap, Baker and his team packed it into six couch-sized coolers and whisked it back to Miami on a donated AmEx cargo flight.

Fabrizio Conejo, a doctoral student in Andrew Baker’s lab, is documenting antlers found on coral reefs in Honduras.

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

hide title

Switch title

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

“It’s been a long day,” Baker said 14 hours later, standing on the tarmac at Miami International Airport waiting to clear customs as the setting sun turned the sky pink.

Baker’s biggest concern is the temperature. The pilot set the cabin temperature to 77 degrees. But even for sturdy corals, 14 hours is a long time. Baker is confident that both brain corals will survive the trip, but he’s not so sure about the antlers.

Andrew Baker (left) removes coral from a reef near Stella, Honduras. Healthy Acropora corals (right) are critically endangered around the world.

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

hide title

Switch title

University of Miami Rosenstiel College

“For those Acropora corals that we’re actually most interested in, they’re notorious for not being very good at traveling,” Baker said.

Amerijet’s crew has transported whales, dolphins and even giraffes on spacious Boeing 767 cargo planes, but never coral. They quickly moved the coolers through a warehouse the size of six football fields to a waiting truck, then drove half an hour to the tanks outside Baker Laboratories on Biscayne Bay.

A forklift at Miami International Airport moves refrigerated containers containing antlers and brain coral that were shipped from Honduras to Miami in June.

Jenny Staletovich/WLRN

hide title

Switch title

Jenny Staletovich/WLRN

When the students and Baker unloaded the cooler at a critical moment, swarms of mosquitoes emerged.

“Okay, let’s get started,” Baker said, opening the first cooler. “It smells like that.”

A sweet and salty smell like scallops wafted out, indicating they had survived hours spent in refrigerated bins, bumped around on forklifts and jostled by airport workers.

Within a day, most corals have acclimated to their new homes, with corals being moved from outdoor raceway tanks to indoor spawning facilities. A total of 37 antlers and brain corals completed the journey. To improve his chances of success, Baker donated seven antlers to the Florida Aquarium, where scientists have successfully propagated the coral.

Coral Futures Laboratory Manager Cameron McMath places staghorn corals in outdoor racetrack tanks to acclimate after departing from Honduras.

Diana Udall/University of Miami Rosenstiel School

hide title

Switch title

Diana Udall/University of Miami Rosenstiel School

Baker said this is the first time corals have been introduced to the United States in an attempt to create more resilient babies. The idea of using exotic corals to do this raises concerns about mixed genetics. Still, those concerns don’t outweigh the risks: Elkhorn, which once blanketed Florida’s reefs, has all but disappeared in the state. The remainder was hit hard by last summer’s heat wave.

Baker said it took a year just to get a permit to bring the coral into the United States. If he succeeds in propagating them, he will need to obtain more state and federal permits to plant them on Florida’s reefs. Baker hopes the corals will spawn in July or August, when Florida corals typically spawn. He could then cross them and let the babies grow while he went through the licensing process.

Baker ultimately hopes he can speed up the evolutionary process currently being overtaken by climate change.

“We can’t just wait for solutions to be ready and then think, ‘Okay, now what do we know?’ How do we save these ecosystems?” he said. “We have to work now to address the larger problem of climate change.” Before, leave something to save. “