Justin Bulley had been in the custody of the Los Angeles County child welfare system, but during a visit with his mother, the toddler was somehow exposed to the county’s most lethal drug.

Within hours, the one-year-old was dead.

The reason: A lethal dose of fentanyl – a synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin – was found in the young child’s blood.

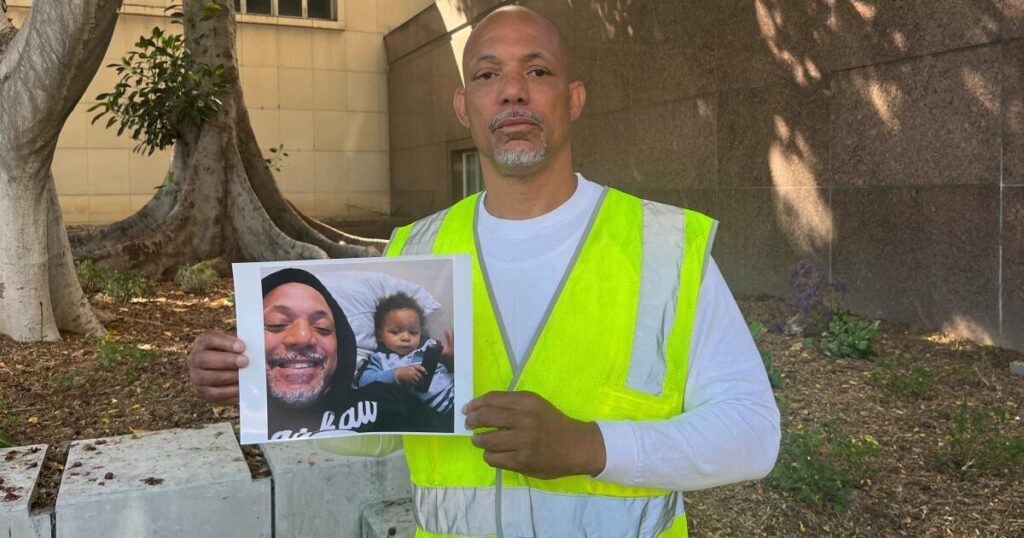

“They robbed me,” said Monteith Buley, Justin’s father. He said he was estranged from the child’s mother, but he also lost custody of Justin when she turned it over to the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services. He said he had been fighting for full custody of his son when the boy died.

Briley, the truck driver, said at a news conference Wednesday that he was still in shock over Justin’s death in February.

“I just miss my son,” said Buley, 51. “I cry almost every day.”

He accused the Department of Children and Family Services of failing to protect his son.

Brian Claypool, an attorney representing two siblings, Brie and Justin, filed a notice of claim with Los Angeles County this week seeking $65 million in damages and intends to file a wrongful death lawsuit against the Department of Children and Family Services .

“How did this happen?” Claypool said. “There’s only one answer: because we have a pathetic Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services in Lancaster. It’s absolutely horrific.

Claypool called Justin’s death the latest in a series of tragedies in which children in the Antelope Valley have died under the department’s radar. Despite several tragic cases that have prompted investigations and changes in leadership, Claypool said Justin’s death shows that needed changes in the nation’s largest child welfare system are still not happening.

“What happened that day should not have happened,” Claypool said. “They’re throwing underserved kids under the bus.”

Claypool also represents the family of Noah Cuatro, a 4-year-old Palmdale boy whose parents tortured and killed him in 2019 ; and 10-year-old Anthony Avalos, who died after being tortured and mistreated at his Lancaster home despite numerous warnings to DCFS.

But the lawyer called Justin’s death “the most egregious case of malfeasance I have ever seen in my lifetime.”

The Los Angeles County medical examiner this month found that Justin’s death on February 18 was caused by “the influence of fentanyl” and ruled it an accidental death. An autopsy report shows the toddler died at Antelope Valley Medical Center in Lancaster, where he was transported after family members found him unresponsive at his mother’s home and called 911.

Paramedics who arrived at the home attempted to administer naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug, to the child, the report said.

His mother told officials that when Justin and his two siblings, ages 3 and 5, came to visit his home, she had been drinking and their grandfather had been snorting fentanyl, according to the medical examiner’s investigation. The report states there are “several versions of what happened at the scene,” but the grandfather told officials the child “at some point interacted with fentanyl.”

An autopsy revealed no other traumatic injuries. The toxicology report found that Justin’s blood contained 25 nanograms per milliliter. The Delaware State Medical Examiner’s report stated that a dose of 4 nanograms per milliliter can cause overdose death in healthy people.

Officers who later searched the home found “glass pipes, bags containing unknown substances and other drug paraphernalia,” some of which were “in an area accessible to children,” according to the forensic report.

No arrests have been made in Justin’s death, but the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department is still investigating the case, said Lt. Michael Gomez, head of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department’s homicide unit. Gomez said detectives are working with the district attorney’s office and a decision on whether to file charges is imminent.

In Claypool’s notice of loss, he claimed that a DCFS worker had been at the home to supervise visitations the day Justin died, but that the worker fled the scene when the child was found unconscious. The document, filed with the county Board of Supervisors, a required first step before a civil lawsuit, alleges that Justin’s siblings also ingested fentanyl.

According to Lt. Gomez, other children in the home at the time of Justin’s death were tested for fentanyl by DCFS, but he declined to disclose those results. He said he was unaware DCFS staff were at the home the day Justin died.

Los Angeles County DCFS spokesperson Shiara Davila-Morales declined to comment or respond to any of the allegations in the case, citing the pending litigation. The New York Times was unable to reach Justin’s mother, Jessica Dathard, for comment.

When Briley spoke about the impending lawsuit Wednesday, he held up a photo of himself and his son and kissed the child’s face.

“I don’t care about money, I want my son,” Buley said.

Claypool argued that Justin and his siblings should not be allowed to visit their mother given her past, including a 2023 conviction for drunken driving and child endangerment, court records show. He also cited his grandfather’s criminal record, which included drug-related arrests.

“For many years, the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services recognized the danger the children were in and allowed their mother and grandfather continued access,” Claypool wrote in the notice of damages.

“There are huge red flags in this case,” Claypool said. “DCFS played Russian roulette with the lives of Justin and his siblings in this matter.”