For adults, the death of a parent is often a heartbreaking and disorienting experience. For children, it’s even worse, triggering feelings of depression and abandonment, and sometimes self-destructive behaviors such as drug use, which can continue into adulthood. This has an especially severe impact when the child is black and therefore more likely to enter the child welfare system.

recent Report The study by federal researchers provides the most comprehensive picture yet of the widespread impact of overdose deaths on black children in Los Angeles and other cities, and what can be done about it.

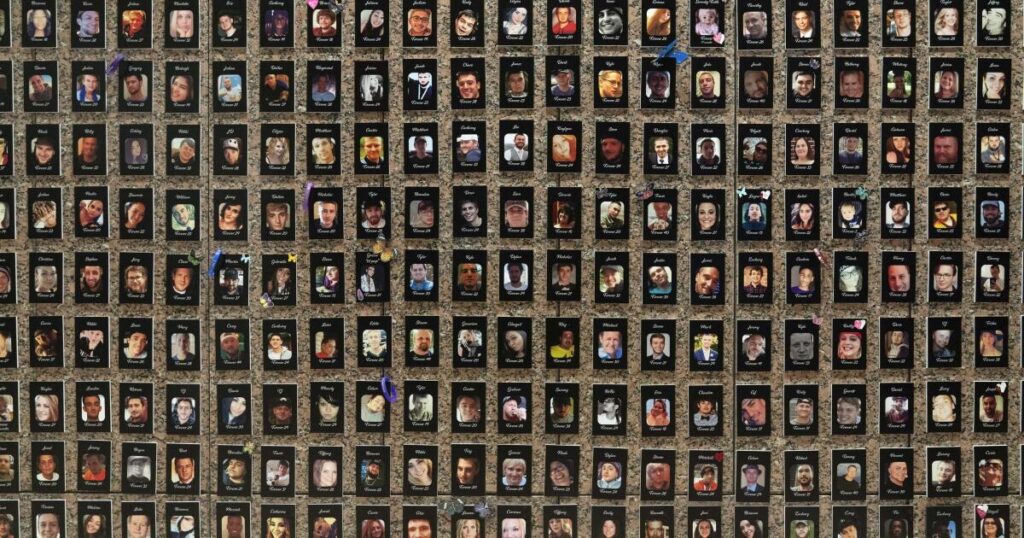

2011 to 2021The report found that more than 321,000 American children have lost a parent to drug overdose. Black children have the highest increase Loss rate over the years, compound interest The long-term public health crisis facing black Americans. Like much of the country, Los Angeles has seen a surge in drug overdoses in recent years. The city’s black adults suffer disproportionate losses.

Black people more likely to experience drug-related deaths With limited access to treatment and resources like naloxone, which can reverse drug overdoses. When they become parents, the impact on their children is both rapid and profound. Parental drug use is closely related to child drug use.

Even though black children make up only 7.4% of the Los Angeles County populationthey represent twenty four% Number of people entering the child welfare system in the most recent year. a study Investigation found that about 47% of black children in California were abused before age 18, with substance abuse accounting for 41% of child abuse cases in the state.

The overrepresentation of black children in Los Angeles’s child welfare system has been under scrutiny since the height of the city’s heroin and crack drug epidemic in the late 1980s. These drugs were later viewed as largely a criminal issue through heavy-handed policing and prosecution, resulting in the premature death and incarceration of a generation of young and middle-aged black Los Angeles men, both users and dealers. Many of their children end up trapped in the city’s broken child welfare system and often follow a similar path toward addiction and entanglements with the legal system.

When a child’s parent dies, other family members – the child’s other parent, grandparents, aunts or uncles – are the first to assume responsibility for their care. But black children, especially those from low-income communities, often end up in the child welfare system.

Why? The child’s surviving family members may lack the resources to fill the gap. But racial bias also tends to lead child welfare workers to remove black children from their families and hinder reunification efforts.

Research consistently shows Child welfare workers more likely to define black parents’ behavior as abuse or neglect Even if it can be compared to the behavior of parents of other races. child welfare workers also More likely to view black families as less loving and less worthy of redemption than their children.

Children who enter the child welfare system due to the death of a parent have spent Time in the system is twice as long. Black children tend to stay in the system longer because of bias.

The twin devastations of Los Angeles’ opioid epidemic and its child welfare system are daunting, but not beyond repair. The first necessary step is to revise the city’s racially biased child removal process. Los Angeles officials have been experimenting with a “blind removal” approach that excludes demographic details such as a child’s race from the decision-making process after an investigation. This is a step in the right direction.

However, UCLA pilot study The program shows that racial inequalities persist, illustrating how deeply entrenched child welfare bias is. For blind elimination to be effective in eradicating racial disparities, it must be accompanied by greater transparency, expanded civil review board and implicit bias training.

Second, we need to better understand the consequences of including black children in the child welfare system. In general, black children in the system are highly stigmatized, especially when they come from families with a history of drug abuse. This helps make them Less likely to be adopted. The trauma of losing a parent also means they are more likely to experience depression and anxiety.

These experiences often lead to social isolation, poor academic performance, limited employment prospects, and incarceration. Officials must identify these patterns early and provide resources like mental health care to stop this harmful chain reaction.

Finally, policymakers must continue to explore the benefits of a guaranteed basic income that provides a buffer for personal and professional growth. Another pilot program in California will Providing a guaranteed basic income for those 21 or older who are no longer in foster care. State governments should lower the eligibility age to 18 to address the serious housing and employment challenges black youth face as adults. Stanford University researchers and others have found that such policies help improve health, housing security, and employment prospects.

Addressing the growing overdose epidemic in Los Angeles’ black community requires focusing not only on the immediate risks drug users face, but also on the childhood experiences that often drive them to use drugs. One of our most powerful tools for preventing future overdoses is better care for the children most directly affected by today’s losses.

Jerel Ezell is an assistant professor of community health sciences at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies the racial politics of substance use.