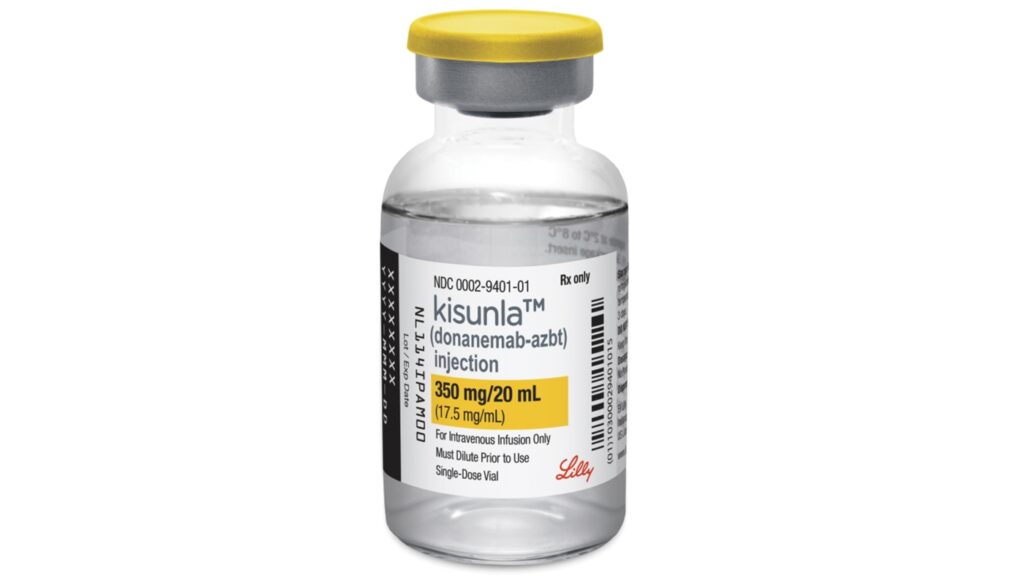

This image provided by Eli Lilly shows the company’s new Alzheimer’s drug Kisunla. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday approved Eli Lilly and Company’s Kisunla to treat mild or early-stage dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease.

AP/Eli Lilly

hide title

Switch title

AP/Eli Lilly

WASHINGTON — U.S. officials have approved another Alzheimer’s drug that modestly slows the disease, providing a new option for patients in the early stages of the incurable, memory-destroying disease.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday approved Eli Lilly and Company’s Kisunla to treat mild or early-stage dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease. It is the second drug to be convincingly shown to slow cognitive decline in patients, following the approval of a similar drug by Japanese drugmaker Eisai last year.

Delays for both drugs spanned months — about seven months in the case of Eli Lilly’s drug. Patients and their families must weigh the benefits against the drawbacks, including regular intravenous fluids and potentially dangerous side effects such as brain swelling.

Doctors who treat Alzheimer’s disease say the approval is an important step after decades of experimental treatments failing.

“I’m excited to have different options to help my patients,” said Dr. Susan Schindler, a neuroscientist at Washington University in St. Louis. “As a dementia specialist, it’s difficult — I diagnose my patients with Alzheimer’s, and then every year I see them progress to the point of death.”

Kisunla and the Japanese drug Leqembi are both lab-made antibodies that are administered intravenously and target the buildup of sticky amyloid plaques in the brain, a cause of Alzheimer’s disease. Questions remain about which patients should take these drugs and how long they may benefit.

The new drug is expected to be approved after an outside FDA advisory panel voted unanimously in favor of its benefits at a public meeting last month. The approval came despite some questions from FDA reviewers about how Eli Lilly was studying the drug, including allowing patients to stop treatment after plaque reached very low levels.

Eli Lilly said the cost varies depending on how long a patient takes the drug. The company also said a year of treatment would cost $32,000, which is higher than Leqembi’s price of $26,500 a year.

The FDA’s prescribing information tells doctors that they can consider stopping the drug after confirming through brain scans that a patient has minimal plaque.

More than 6 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease. Only those with early-stage or mild disease will qualify for the new drug, and an even smaller number may go through the multi-step process required to get a prescription.

The FDA approved Kisunla (chemical name: donanemab) based on results from an 18-month study in which patients who received the treatment experienced memory and cognitive decline about 50% slower than those who received a dummy infusion. twenty two% .

The main safety concerns are brain swelling and bleeding, common to all plaque-targeting drugs. The rates reported in Eli Lilly’s study, which included 20% of patients experiencing microbleeds, were slightly higher than those reported by competitor Leqembi. However, the two drugs were tested in slightly different types of patients, which experts say makes it difficult to compare the drugs’ safety.

Compared to Leqembi’s twice-monthly regimen, Kisunla’s monthly injections make it easier for caregivers to bring loved ones to a hospital or clinic for treatment.

“Certainly, monthly infusions are more attractive than biweekly infusions,” Schindler said.

Eli Lilly’s drug has another potential advantage: Patients can stop taking it if they respond well.

In the company’s study, patients stopped taking Kisunla once their brain plaque reached barely detectable levels. Almost half of patients reach this point within a year. Discontinuing medication can reduce the costs and safety risks of long-term use. It’s unclear how long it will take for patients to resume infusions.

Logistical hurdles, spotty insurance coverage and financial problems have slowed the launch of rival Leqembi, which Eisai markets with U.S. partner Biogen. Many small hospitals and health systems are not ready to prescribe new plaque drugs for Alzheimer’s disease.

First, doctors need to confirm that people with dementia have the brain plaques targeted by the new drug. They then need to find a drug infusion center where the patient can receive treatment. Meanwhile, nurses and other staff must be trained to perform repeat scans to check for brain swelling or bleeding.

“These are things that doctors have to set up,” said Dr. Mark Minton, head of Eli Lilly’s neuroscience division.