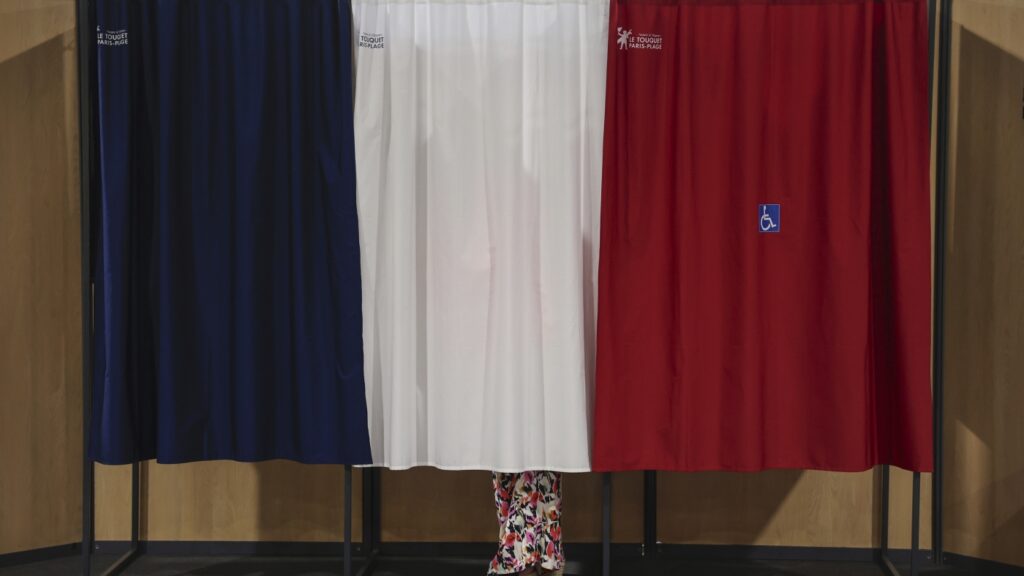

A voter stands at a polling station during the second round of legislative elections in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage in northern France on Sunday.

Mohammad Badla/AP

hide title

Switch title

Mohammad Badla/AP

PARIS — A crucial runoff vote is underway in mainland France on Sunday that could hand a historic victory to the far-right national rally led by Marine Le Pen and her inward-looking anti-immigration vision, or lead to parliament Suspension and political gridlock.

French President Emmanuel Macron made a huge gamble by dissolving parliament and calling elections after defeating centrists in the European elections on June 9.

A snap election in the nuclear-armed country would have implications for the war in Ukraine, global diplomacy and European economic stability, and would almost certainly undermine the remaining three years of Macron’s term as president.

In the first round of the election on June 30, the anti-immigration nationalist national rally led by Marine Le Pen achieved its largest ever victory.

More than 49 million people have registered to vote in the election, which will decide which party controls the 577-member National Assembly, France’s influential lower house, and who will be prime minister. If support from Macron’s weak centrist majority erodes further, he will be forced to share power with parties opposed to much of his pro-business, pro-EU policies.

Voters in Paris polling stations are keenly aware of the far-reaching implications for France and beyond.

“Today, personal freedom, tolerance and respect for others are at risk,” said voter Thomas Bertrand, 45, who works in advertising.

Racism and anti-Semitism, as well as a Russian online campaign, have marred the campaign, with more than 50 candidates reportedly being physically attacked – highly unusual for France. The government will deploy 30,000 police officers on polling day.

French President Emmanuel Macron (right) holds the second round of legislative elections in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage in northern France on Sunday.

Mohammad Badla/AP

hide title

Switch title

Mohammad Badla/AP

The heightened tensions come as France celebrates a very special summer: Paris is about to host an ambitious Olympics, the national football team is in the semi-finals of the 2024 European Championships and the Tour de France is being held across the country alongside the Olympic torch.

According to statistics from the French Ministry of the Interior, as of noon local time, the turnout rate was 26.63%, slightly higher than the 25.90% announced at the same time as the first round of voting last Sunday.

Turnout of nearly 67% in the first round was the highest since 1997, ending nearly three decades of growing voter apathy towards legislative elections and, for a growing number of French people, towards politics in general. .

Macron and his wife Brigitte voted in the seaside resort town of La Touquet. Prime Minister Gabriel Attal earlier voted in the Paris suburb of Vanves.

Le Pen did not vote as her constituency in northern France did not have a run-off vote after winning her seat outright last week. Across France, 76 other candidates secured seats in the first round, 39 from her national rally and 32 from the left-wing New Popular Front alliance. Two candidates from Macron’s centrist slate also won seats in the first round.

Elections in mainland France and Corsica will end at 8pm (1800 GMT) on Sunday. Preliminary polls are expected to be released late Sunday, with preliminary official results expected later Sunday and early Monday.

Voters living in the Americas and in the French overseas territories of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, Saint-Barthelemy, Saint-Martin, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyana and French Polynesia cast their ballots on Saturday .

If the National Rally wins an outright majority and its 28-year-old leader, Jordan Bardella, becomes prime minister, the election could give France its first far-right government since the Nazi occupation in World War II. The party topped last week’s first round of voting, followed by a coalition of centre-left, far-left and Green parties and Macron’s centrist coalition.

Pierre Lubin, a 45-year-old business manager, worries whether the election will produce an effective government.

“That’s a concern for us,” Lubin said. “Will it be a technocratic government or a coalition of (various) political forces?”

The outcome remains highly uncertain. Two rounds of polls showed the National Assembly could win the most seats in the 577-seat National Assembly, but fell short of the 289 seats needed for a majority. It would still make history if a party with historical ties to xenophobia, downplaying the Holocaust and long considered a pariah became the largest political force in France.

If it wins a majority, Macron will be forced to share power with a prime minister who disagrees deeply with the president’s domestic and foreign policies, an awkward arrangement known in France as “cohabitation.”

Another possibility is that no one party obtains a majority, resulting in a hung parliament. That could prompt Macron to enter into coalition talks with the center-left or appoint a technocratic government without political affiliations.

Whatever happens, Macron’s centrist camp will be forced to share power. Many of his coalition’s candidates failed or dropped out in the first round, meaning not enough people entered the race to come close to the majority he received when he was first elected president in 2017, or the legislative majority he would receive in 2022 vote.

Both events are unprecedented for modern France and make it more difficult for the EU’s second-largest economy to make bold decisions on arming Ukraine, reforming labor laws or reducing its massive deficit. Financial markets have been jittery since Macron surprised his closest allies by calling snap elections in June after France’s National Rally won the most seats for France in European parliamentary elections.

No matter what happens, Macron said he will not step down and will remain president until the end of his term in 2027.

Many French voters, especially in small towns and rural areas, are frustrated by low incomes and a political leadership in Paris that is seen as elitist and uninterested in workers’ daily struggles. National rallies often connect with these voters by blaming immigrants for France’s problems, and have gained broad and deep support over the past decade.

Le Pen has softened many of her party’s positions – she no longer calls for withdrawal from NATO and the European Union – to make her selection easier. But the party’s core far-right values remain. It wants a referendum on whether being born in France is enough to gain citizenship, limiting the rights of dual citizens and giving police more freedom to use weapons.

With the uncertain outcome of a high-stakes election looming, legal expert Valerie Dodeman, 55, said she was pessimistic about France’s future.

“No matter what happens, I think this election will leave dissatisfaction on all sides,” Dodman said.