Voting methods are the core process of an election, specifying what information is collected from voters and how the collected information is used to determine the winning candidate. The U.S. Constitution is silent on how voting should be conducted. The simplest, “pluralism,” has historically been the default and remains the dominant method of voting in American public elections. Majority system allows each voter to vote only for Single candidate. The candidate with the most votes is the winner.

Around the time of the American Revolution, two French scholars, Jean-Charles de Borda and Nicolas de Condorcet, identified some serious problems with pluralism. A 240-year debate ensued. Various voting methods have been proposed and considered to be the best alternatives to majority voting. If any one of the many arguments was indeed sound, convincing, and demonstrably superior to all others, pluralism would long ago be superseded and the nation would live happily ever after. The only broad consensus, however, is that pluralism does need to be replaced. This was worse than Condorcet and Borda imagined.

Diversity is killing us. This is one reason for the growing polarization that is tearing at the fabric of our society. It forces voters to elect a president whom a majority of voters reject. People are tired of having to vote for “The lesser evil.”

A new voting method AADV (Approve/Approve/Disapprove Voting) was proposed in 2020. Pros and cons are summarized separately for each candidate. Disapprovals are then subtracted from approvals to obtain net approvals for each candidate. The candidate with the most (positive) net support is declared the winner. If no candidate receives positive net support, NOTA (None of the Above) wins. If NOTA wins, all candidates will be disqualified and new candidates will have to be re-elected.

The AADV promised to put an end to the debate by resolving the issue of voting methods to the greatest possible extent. Here’s the logic supporting that claim.

The first step in designing or choosing a good voting method (or anything for that matter) is to correctly and succinctly define what a good voting method should do. Everyone should readily agree that the first and most important purpose of any (public) election is to make the “best” selection of candidates for the position to be filled (but to retain decision-making power “reasonably decentralized”). Quite a few of voters will make these decisions; we have no choice but to comfortably assume that they do have the knowledge and wisdom to create good work.

When it comes time to vote for a particular race, every voter has an “opinion” in his or her mind about each candidate in that race. Sometimes this view has a strong positive effect on a candidate they consider “very good” – if that candidate wins, voters will be very happy and satisfied. Sometimes opinions can be very negative and voters can be very dissatisfied if a candidate wins. Of course, voters’ satisfaction with a candidate can range between strongly positive and strongly negative, including zero (no opinion). It also often happens that voters have zero opinion on a candidate because they don’t understand the situation and don’t know the candidate at all and therefore can’t have any opinion – most elections with three or more candidates have a lot of this Types of no opinion.

There are a lot of voters, and everyone has their own set of opinions about each candidate in the race. It is possible (almost certainly true for a large number of voters) that some voters will have a positive opinion and others a negative opinion of any given candidate; some of them may have no opinion at all. How should the voting method process this data to identify the correct winner?

The only reasonable conclusion to draw is that the best candidate, that is, the candidate who best represents the collective opinion of voters, is the candidate with the highest (or most positive) net worth of all opinions (i.e., positive opinions minus negative opinions). No amount of “no comments” can influence the decision in any way. Therefore: the best choice is the outcome (selected candidate) that maximizes voter satisfaction (net of dissatisfaction) when summing over all voters who voted. There is no better way to translate the collective knowledge, judgment and wisdom of voters into the best choices. This is the first and only aim that a voting method must have.

There has been considerable debate over the “fairness” of various voting methods. This is not a critical question. Neither definition says anything about “fairness,” so such arguments are misleading. If one is concerned about fairness, however, it is hard to imagine a fairer outcome than consistently selecting the candidate in every election who maximizes voter satisfaction (as the definition specifies).

To understand the consequences, consider the simplest election: one with only one candidate. In fact, many states implement single-candidate open elections. They are called “judge retention elections.” In all respects, these are single-candidate elections—voters vote to elect (or not elect) one candidate to serve in some capacity for a certain number of years.

How does the plurality system work in single-candidate elections? not good at all! Since majority vote only allows each voter to vote for A candidate who will always be chosen. That’s why judges reserve elections to allow voters to vote “yes” or “no” (satisfied or dissatisfied). The “no” votes are subtracted from the “yes” votes, and the total must be a positive number (more “yes” votes than “no” votes) to re-elect a candidate. This is called a “referendum”.

However, in regular elections, there are indeed many elections in which only one candidate is on the ballot and majority voting is used. These are sham elections because voters have no ability to reject the candidate or otherwise influence the outcome. Note that instant runoff voting (in fact, all Ranked choice methods), ratification voting, STAR voting, Condorcet (and basically every other advocated method) all suffer from the same problem: they do not allow any voter to express dissatisfaction with any candidate.

Now, consider a two-candidate election in which one of the two candidates is elected. It is necessary to determine the degree of voter satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) if candidate A is elected, and the degree of voter satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) if candidate B is elected. The candidate with whom voters are most satisfied will be designated as the winner. But it’s certainly possible that voters will be dissatisfied with either candidate. As with single-candidate elections, it is critical that voters have the ability to reject one or even both candidates. As with single-candidate elections, the opinions of voters who are dissatisfied with a candidate clearly should not and should not be ignored.

Obviously, these conclusions for one- and two-candidate elections also apply to any number of candidates. If the voting method is to select the winner with which voters are most satisfied, then voter dissatisfaction cannot be ignored and must offset other voters’ satisfaction with each particular candidate.

AADV allows a limited number of approvals and denials. It works very well for any number of candidates, including one. However, no real-world voting method is perfect, and AADV is certainly no exception.

It has been shown (Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem, by extension) that every form of voting (except dictatorships) can be manipulated to some extent through strategic voting. No voting method is completely immune to this degradation, but some voting methods are more susceptible to it than others. This is a trade-off that must be considered when designing or choosing a voting method.

AADV optimizes this trade-off by collecting the two most important data items—the candidate each voter thinks is the best and the candidate each voter thinks is the worst—and nothing more. Allowing a second ratification is to remove any incentive to vote for the “lesser of two evils” rather than each voter’s sincere first choice. Allowing additional voter input is expected to reduce performance; additional data cannot significantly aid decision-making, so it can only be harmful noise and/or an attempt to manipulate results through insincere “strategic” voter input.

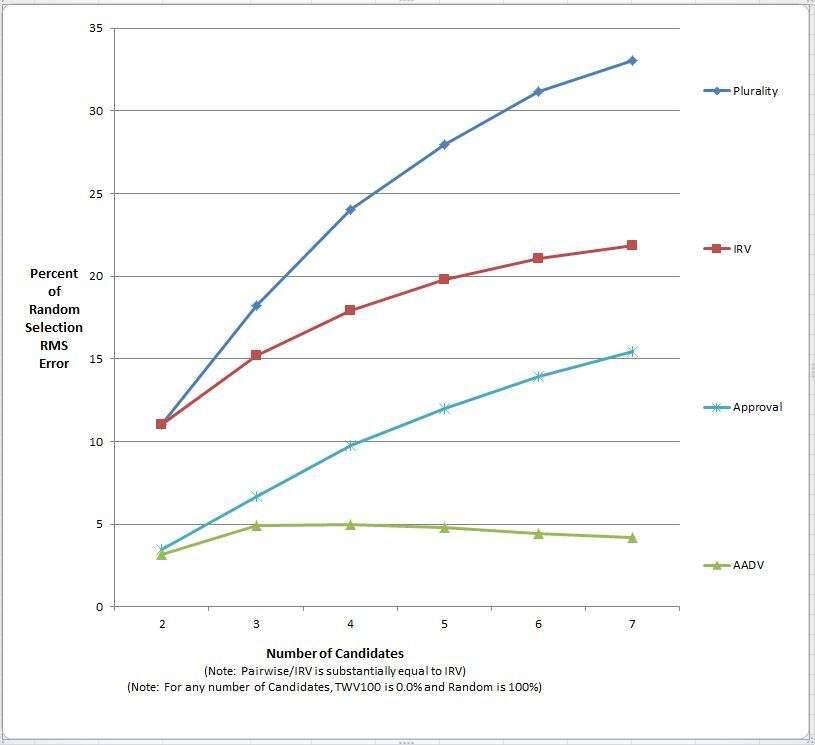

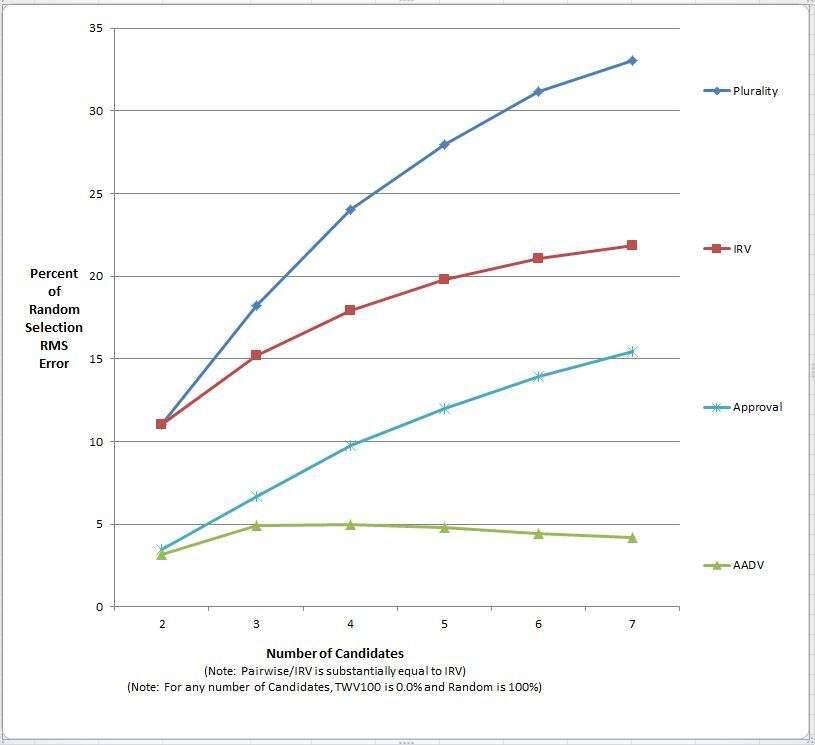

It is known that all voting methods sometimes make mistakes (i.e. fail to identify candidates that maximize voter satisfaction). Obviously, an approach that minimizes errors and does not make major mistakes (such as electing a candidate that a majority of voters oppose) is preferred. Logically, AADV is as close to the best it can be, but how good is it? The attached figure summarizes the RMS (root mean square – something like an average) error for various voting methods in 600,000 simulated elections of every possible type; each election had 10,000 voters casting their votes in good faith.

AADV offers such improvements that it can qualitatively improve elections. Political parties will no longer nominate highly divisive candidates because they will face much opposition and perform poorly. The winner will be the candidate with broad appeal and few downsides; healthier. Therefore, AADV will tend to reduce polarization rather than increase it like diversification does. Electing candidates who are disliked by the majority of voters will become a thing of the past. The “playing field” should become more level so that all candidates receive reasonable media coverage and serious voter consideration. AADV continues to work well when a large pool of candidates eliminates or significantly reduces the need for runoffs, and should be expected to field more broadly acceptable candidates in primaries.