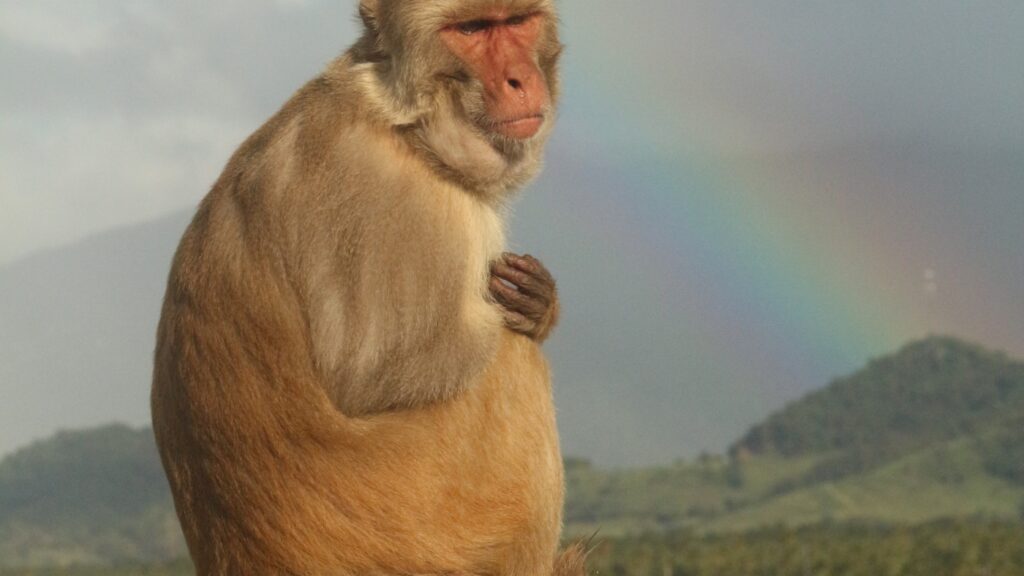

In February 2022, a macaque sat on a rock on Santiago Island as a rainbow streaked across the sky.

Lauren Brent

hide title

Switch title

Lauren Brent

In September 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico. Although it is uninhabited, it is home to hundreds of rhesus monkeys.

The monkeys have been roaming the island since 1938, when an American primatologist brought their ancestors from India to establish an experimental site to study the primates in the wild.

“It’s a great place to study their behavior, genetics and cognition,” said Lauren Brent, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Exeter. “It’s where most of what we know about this species comes from. ”

Santiago Island is small, only about half an hour’s walk away, and its rhesus monkeys are known for being intolerant, hierarchical and aggressive – researchers describe them as “authoritarian and nepotistic”.

“They’re notoriously competitive,” Brent said. Momentarily imagining herself as one of the monkeys, she added: “I form alliances with a few members of the group and we pursue what we want against other group members or another group.”

Island life for the macaques hasn’t changed much over the years. But in September 2017, Hurricane Maria destroyed their home. Now, in research published in the journal Science, Brent and her colleagues report that the disaster appears to have fundamentally changed the monkeys’ society.

A ravaged home

Days after Hurricane Maria ripped through the Caribbean, one of Brent’s colleagues recorded footage of the island from a helicopter. “This is the first time anyone has actually witnessed the devastation happening on San Diego Island,” she said.

Somehow, most of the 1,800 monkeys survived. “We don’t know where they went,” Brent said, “or how they did it.”

However, the island itself was devastated. Almost two-thirds of the vegetation was destroyed. That means the monkeys have far fewer shaded spots to escape temperatures of more than 100 degrees. “You’re just exposed to the sun’s rays,” Brent said. All that remains is “the shadow of a small puddle.”

Camille Testard, a neuroscientist and behavioral ecologist who was in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania at the time, remembers how desperate the macaques were.

“You would have a scene of a dead tree, and there would be a shadow behind it,” Testard said. “Just this one row – the monkeys will be in that row. There will even be some animals following us in the shade of our trees.”

In March 2022, macaques lined up under the shade of a dead tree.

Lauren Brent

hide title

Switch title

Lauren Brent

But Testard and her colleagues in Puerto Rico noticed something else. Despite the limited shade, the macaques did not quarrel over it. They seem to be more tolerant of each other.

Test tolerance

This led Testad to compare the monkeys’ social interactions five years before and five years after the hurricane. She found that macaques were more likely to sit closer together in the shade and in groups.

“So it’s not just me sitting next to my favorite monkey more,” she explained. “I just sat next to a lot of new monkeys that I’d never sat next to before.”

Testard observed that the animals were also in close proximity to each other at other times of the day, not just when sharing shade.

Surprisingly, the macaques’ overall levels of aggression dropped. “This is the exact opposite of what we imagine primates to do,” Brent said.

Testard’s theory is that aggression makes monkeys hotter.

“What you want to do is lower your body temperature as effectively as possible,” she said. “Being aggressive – that really raises your body temperature.” So staying calm is actually a way to stay calm.

Brent was surprised to find that monkeys changed their social structure in the face of habitat change. “Yes, animals are using their social lives to cope with challenges,” she said. “But number two, they’re flexible in how they do it. They can change what social networking looks like.”

Additionally, macaques that had more social partners on average (which meant more opportunities for shade) were 42% less likely to die. Mortality rates were unchanged. Instead, “the factors that predict their survival have changed,” Testard said. “These partnerships can help you get shade to lower your body temperature, [are] It’s really critical for these animals.

Jorg Massen, an ethologist at Utrecht University who was not involved in the study, said the research is in some ways related to people’s understanding of social plasticity in some primates. The new understanding is consistent.

“Of course, this flexibility is not unlimited,” he argued. “There is some flexibility, but we shouldn’t overestimate it.”

Massen is curious about the mechanisms driving this change. “How did these normally intolerant macaques suddenly become so tolerant?” he wondered. “What hormones underlie this behavior, and maybe it’s even genetic or epigenetic?”

Climate change is altering habitats around the world, posing challenges to animal populations around the world.

“With the increase in natural disasters and other types of ecological changes, this need for rapid change is becoming more common,” explains Testad.

Through their social flexibility, macaques show us one way some species may try to adapt, she said.