The Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation and Scotts Valley Pomo Indian Tribe come from adjacent lands that stretch from the vineyards of wine country to the redwood forests of Northern California.

Their ancestors spoke different languages but communicated through common dance gestures for generations. Despite a history of violence at the hands of outsiders and being forced from the territory they had called home for centuries, both tribes persevered.

Now, a dispute over a casino has driven a rift between the two tribes and raised questions about the way the U.S. government compensates for stealing their land and threatening their culture.

At issue is a 128-acre hillside parcel in Solano County near the tidal flats of San Pablo Bay, a 45-minute drive from San Francisco.

The Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians wants to build a $700 million casino resort on 128 acres in Vallejo, east of San Francisco.

(Jason Almond/Los Angeles Times)

The Scotts Valley Band wants the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs to place the land into a federal trust so that the tribes and investors who own the land can build a $700 million casino resort on it.

The Trump administration rejected a request to place the land into trust in 2019, arguing that Scotts Valley did not yet have enough historical ties to the site to receive approval. But in 2022, a federal judge overturned that decision, saying the government overstepped its authority and made the decision based on faulty reasoning.

Now the Yocha Dehe Nation is accusing the Biden administration of reviving the project without seriously considering opposing the plan.

Yocha Dehe leaders maintain that the property is the traditional homeland of the Patwin ancestors and that the tribe should have a say in what happens on the land.

“It’s a little disrespectful to have a tribe come from over 90 miles away to develop something in our homeland,” said Anthony Roberts, chairman of the Yocha Dehe Tribe.

Jesse Gonzalez, vice chairman of the Scotts Valley Tribe, disputed the Yocha Dehe Tribe’s description of the project, saying his tribe has been vocal about their goals for the land and their access to the land. Be transparent about the reasons why construction is justified.

“For generations, our people have faced tremendous hardship, including the loss of ancestral lands, leaving us as one of the few landless Indian tribes in the United States,” Gonzalez said in an email. “This plan The painting represents a transformative opportunity to reverse this history, allowing our tribe to rebuild and build a sustainable future for our members.”

The Scotts Valley project promises to become one of the North Bay’s most eye-catching landmarks. Plans call for an eight-story gaming center with a casino that would be open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, as well as restaurants, event and banquet halls and adjacent development that would include 24 single-family homes and a Tribal Administration Building. The plan also sets aside 45 acres of land as a biological reserve.

The casino is expected to create 3,640 full-time jobs, a boon for a county with the highest percentage of people below the federal poverty line in the Bay Area, according to data collected by the county.

Farmland of the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation in Brooks, California.

(Jason Almond/Los Angeles Times)

A spokesman for the Office of the Assistant Secretary of State for Indian Affairs said the agency had no further comment on the project beyond a one-page email sent to The Times confirming that a 30-day public comment period on the environmental impact review was underway.

Leland Kinter, 48, the treasurer of the Yocha Dehe Tribe, said his biggest regret, besides what he sees as an air of secrecy surrounding the project, is that leaders from his tribe and the Scotts Valley Tribe have lost control over the dispute. There has been no meaningful contact in years.

In a show of solidarity, he said, the Yochadah Nation once offered financial aid to the Scotts Valley tribe if they agreed to build homes on a more culturally appropriate site.

“We haven’t spoken to them since then,” Gent said.

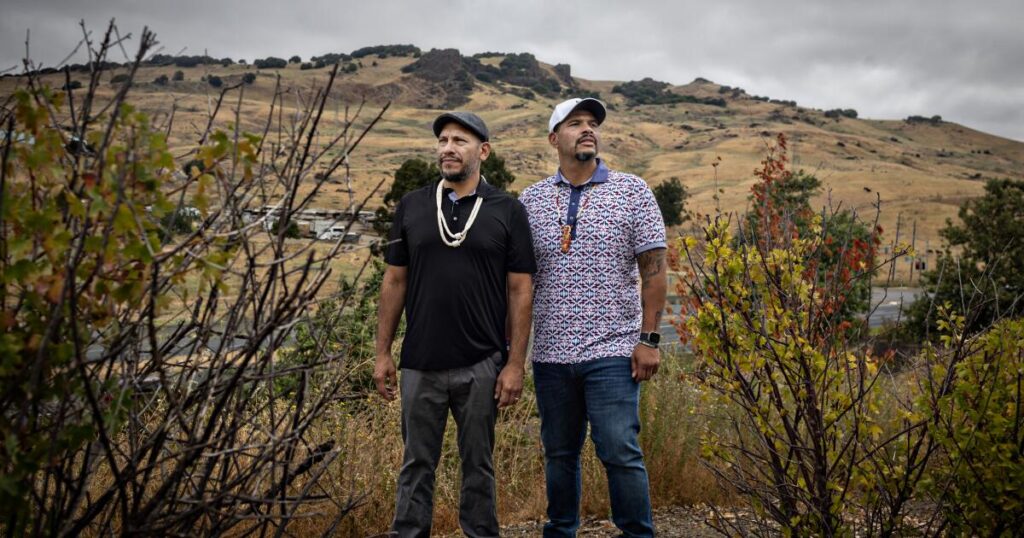

Anthony Roberts, tribal chairman of the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation, wears indigenous jewelry made from abalone shells.

(Jason Almond/Los Angeles Times)

On a recent morning, Roberts and Gent surveyed the proposed casino site in a parking lot at the junction of Interstate 80 and California State Route 37.

Rugged outcrops rise among the mountain’s golden slopes and oak groves, and cows graze on a lonely pasture. Grooves in the hillside wind down to pasture and bike paths at the base.

Ginter and Roberts say the indentations are river beds that their Patwin ancestors remembered when they needed water. Tribal messengers known as “runners” would spend their days rushing from village to village on such hills and ridges, while miners quarried stone from the mountains to make mortars and other tools, they said.

Roberts, 52, doesn’t understand that such a large-scale development wouldn’t desecrate a place that is sacred and historic to his people. He wonders how the project seems to be progressing with limited input from his tribe or the public.

The Solano County Board of Supervisors, members of California’s congressional delegation and other leaders have also expressed opposition to the Scotts Valley Band’s attempts over the years to build a casino in the area.

In an opinion for the Scotts Valley Band, U.S. District Court Judge Amy Berman Jackson wrote that the whole reason for Indian gaming laws was to allow dispossessed tribes “to gain access to their former enjoy a certain status and have the opportunity to make a living financially”.

But Yocha Dehe leaders question why Scotts Valley is seeking to use a special provision in the law that allows federally recognized tribes to build casinos outside of their traditional bases – as long as it shows both modern connections and ” Significant” historical connection to the parcel of land it wishes to establish.

Roberts said Scotts Valley cannot meet that threshold.

The Yochadje River’s ancient connection to Solano County is evident in many ways, Roberts said. The tribe has been involved in efforts across the North Bay to identify and properly dispose of Patwin burial sites, human remains, ancient ruins and mounds where ancestors who lived near the shoreline deposited discarded mollusk shells.

The men said they were convinced the casino package also contained unearthed artifacts.

Near the Solano County Superior Court in Fairfield stands a statue of Chief Solano, leader of the Suisune people of the Patwin people in the Suisun Bay region of Northern California.

(Jason Almond/Los Angeles Times)

The county was named after Patwin Suisun leader Sem-Yeto, who was named Spanish missionary Francisco Solano at his baptism. A 12-foot-tall statue of Chief Solano with his hands raised stands outside an event center in Fairfield County. According to the county’s official homepage, several towns in the county are phonetically related to the village of Patwin – Suisun, Soscol, Ulatis and Putah.

The tribe recently partnered with the Solano Land Trust to rename the 1,500-acre Rockville Hills Regional Park Patwino Worrtla Kodoi Dihi, meaning “Patwin’s Nanyan Homeland”.

For Roberts, the casino dispute is about more than Indian gaming rights and capitalism. Yocha Dehe runs his own successful casino, golf resort and large farm in northern Capay Valley near Brooks City.

It’s about a people’s ability to maintain their culture and influence in a state where Aboriginal societies were once at risk of being wiped out.

The casino split comes as landless and reservation tribes move toward reclaiming and jointly managing stolen territory in California.

Members of the Auckland Aboriginal woman-led Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and the Lisjan Nation Alliance Village recently held a celebration to mark their protection of the 2.2-acre sacred site at West Berkeley Shellmound.

On the fifth anniversary of Governor Gavin Newsom’s apology to California’s indigenous people for the injustices they suffered, he recently announced that the state will help the Shasta Indian Nation reclaim 2,800 acres of ancestral land as part of the demolition process Part of the nearby historic Klamath River Dam and Reservoir.

The Yocha Dehe Tribe’s advocacy helped secure President Biden’s recent expansion of Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument and the renaming of a sacred mountain within the monument to Molok Luyuk (Patwin meaning “Condor Ridge”) in honor of this endangered species The importance of birds in tribes.

Gonzalez said his tribe’s presence in the area is also well-documented, with his ancestors ceding the land in an unratified treaty in 1851.

“America seeks this land from our ancestors because of their long presence and use of this area,” Gonzalez said. “In fact, the federal government recognizes and affirms the ancestral authority of the Scotts Valley to cede land.”

Clear lake view.

(Jason Almond/Los Angeles Times)

The Scotts Valley Pomo Indian Band is headquartered just west of the Patwin area of Lake County, near the site of one of the most horrific acts of violence against Native people in U.S. history.

A small historical marker next to Clearwater Lake on the newly reclaimed road is a reminder of the Bloody Island Massacre in Bono Boti. On May 15, 1850, U.S. cavalry, aided by vigilantes, killed dozens of Pomo people, most of them women and children, on the false suspicion that they were involved in the killing of two white settlers.

This aggression forced the Pomos further away from the lakes, including North Bay.

In court documents defending the casino, Scotts Valley noted that Chief Augustine, one of today’s band’s most important ancestors, was baptized at a mission not far from Sonoma Vallejo.

Augustine and other displaced Pomo people served as forced laborers in the region—raising livestock, grazing livestock on San Pablo Bay, and building adobe homes in Sonoma. Most end up back in Clear Lake.

The site of the Bloody Island Massacre, the 1850 massacre of California natives by U.S. cavalry at Clear Lake in Lake County.

(Jason Almond/Los Angeles Times)

The Pomo and Patwin suffered further indignity in the 20th century when the United States designated them small reservations, only to reverse course in the 1950s and 1960s, stripping them of their land and the federal government recognized status. The tribes must fight through the courts to regain federal recognition, the legal status necessary to have land held in trust for them to build on.

In a 2022 ruling, a federal judge said the cycle of government theft, restitution and retraumatization continues.

In rejecting the Scotts Valley, Berman Jackson writes, the Trump administration “failed to face the inescapable historical fact that the Scotts Valley was a tribe whose recognition and land had been stripped by the federal government and whose The people fled in all directions.”

Roberts and Gent do not deny that the Scotts Valley Pomo deserve justice for their atrocities and land grabbing. But while Berman-Jackson denies that a casino would put the Yocha Dehe at a disadvantage, its leaders counter that the casino plan represents an example of the United States unfairly violating the sovereignty of one tribe to make up for an injustice done to another. .

“Two wrongs do not make a right,” they say.

“The Pomo people have their own story surrounding the lake — it’s a very dynamic history,” Gent said. “The history here is ours.”