You may have never heard of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI), let alone that it is commonly abused. However, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) wants to ban the synthetic hallucinogen, a promising research chemical that has appeared in more than 900 published studies, by listing it on its list of controlled substances. In Schedule I of the Act, this category is said to be reserved for drugs with high concentrations. . Students for Reasonable Drug Policy (SSDP), which defeated the DEA’s attempt to ban the DOI in 2022, has decided to block the measure again.

On Tuesday, SSDP submitted a pre-hearing statement on behalf of more than 20 scientists opposing the inclusion of the DOI in Schedule I. The I license “involves a daunting array of red tape and substantial costs, which can be prohibitive for many research institutions, especially small laboratories and academic departments.” The SSDP also opposes approval of another psychedelic drug2, 5-dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine (DOC), which is also subject to the same proposed rule issued by the DEA on December 13.

“DOIs and DOCs are important research chemicals with essentially no evidence of abuse,” said SSDP attorney Brett Phelps. “We are pleased to be able to fight on behalf of SSDP scientists so that they can continue the critical work they are doing on these substances. “

Phelps is working with Denver attorney Robert Rush, who represents UC Berkeley neuroscientist Raul Ramos. “The DEA’s attempt to classify a DOI—a compound important to both psychedelics and basic serotonin research—as a Schedule I substance reflects an agency overstepping its boundaries,” Rush said. “The government acknowledges that the DOI has not been diverted to uses other than scientific research, but still insists on placing this substance in such a strict category that it would disrupt virtually all current research.”

The SSDP describes both compounds as “essential research chemicals in preclinical psychiatry and neurobiology, and their status as non-scheduled compounds makes them de facto tools for researchers studying serotonin receptors”. In particular, the report says, DOI is “a cornerstone of neuroscience research because of its

The 5-HT2A serotonin receptor is a key component in understanding and potentially enhancing the therapeutic effects of psychedelics.

The SSDP notes that “more than 80% of antidepressant drugs on the market affect the serotonin system” and says scientists have used the DOI to “map the localization of important serotonin receptors in the brain that are involved in learning, memory and psychiatric disorders. Crucial. It added that studies using DOI “show encouraging results in controlling pain and reducing opioid cravings, providing a beacon of hope in the ongoing opioid crisis.” “

The DEA is concerned that DOIs and DOCs “are likely to be misused.” The report noted that both drugs “have been discovered by U.S. law enforcement,” indicating they have “potential for abuse.” According to a review by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), “People use DOIs and DOCs because of their hallucinogenic effects and in doses high enough to cause harm to their health.”

The DEA acknowledged that while DOIs and DOCs “can be purchased from legitimate chemical synthesis companies because they are used for scientific research,” there is “no evidence that they are diverted by these companies.” Still, because “DOIs are not found in FDA-approved drugs and DOC” so people who use them must “do so voluntarily and not on the basis of medical advice from a legally licensed practitioner.”

According to the DEA, any Using a DOI or DOC is abuse by definition. “Anecdotal reports online indicate that individuals are using substances they identify as DOI and DOC because of their hallucinogenic effects,” it noted, referring to descriptions of DOI and DOC experiences on sites like this one. erovid. The DEA added that from 2005 to 2022, the National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) collected 40 DOI reports and 790 DOC reports, averaging approximately 2 and 46 reports per year, respectively.

In 2022, NFLIS collected nearly 1.2 million drug reports, so these compounds combined accounted for approximately 0.004% of the total. Unsurprisingly, the system’s annual report doesn’t even mention a DOI or DOC. They are apparently classified as “other phenylethylamines” and together account for less than 0.2% of all drug reports.

Notably, there is no evidence in the DEA’s proposed rule that recreational use of DOI or DOC is common, let alone that it has resulted in serious, widespread harm. The DEA acknowledges that “to date, there have been no reports of distressing reactions or deaths related to DOI in the medical literature.” But “in 2008, 2014, and 2015, three reports of adverse events related to DOC have been published. Reports include, but are not limited to, seizures, agitation, tachycardia, hypertension, and one death.”

The DEA explains that because “DOI and DOC have similar mechanisms of action and produce similar physiological and subjective effects as other Class I hallucinogens such as DOM, DMT, and LSD…” they “pose the same public health risks of”. Although these risks, such as “hallucinogenic effects, sensory distortion, impaired judgment, [and] The DEA says “strange or dangerous behavior” is primarily “at the user’s risk” and “they can impact the public, just like drunk driving.” The DEA considers “hallucinogenic effects” and “sensory distortions” to be “risks” that speak volumes on its attitude to psychedelics and its refusal to acknowledge that they offer any potential benefit.

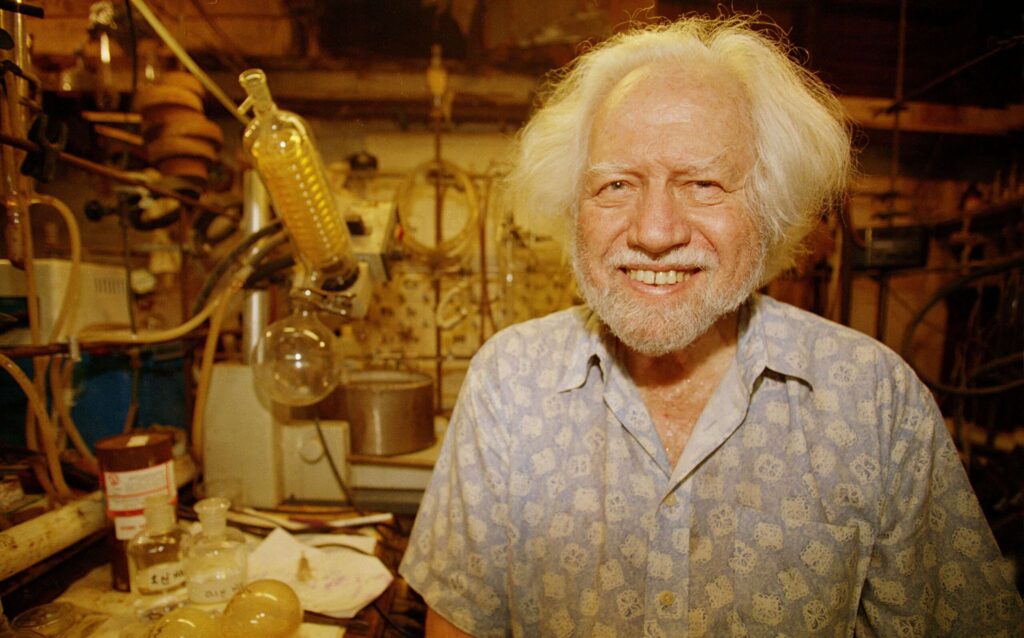

As the DEA points out, the psychotropic effects of DOI and DOC are similar to those of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM, also known as STP), which was first synthesized in 1963 by psychonautical chemist Alexander Shulgin compound of. PIKHAL: A chemistry story,Shulgin also described his synthesis and exploration of ,DOI and DOC.

DOM has been listed on Schedule I since 1973.

Even as a matter of bureaucratic decision-making, this seems to be the basis for listing DOIs and DOCs in Schedule I. Shi stated in his pre-hearing statement. “DEA acknowledges that DOI can be purchased from legitimate chemical companies because it is used for scientific research and that there is no evidence that these companies diverted DOI. DEA acknowledges that clinical studies of DOI have not been conducted in healthy human volunteers and has not yet evaluated the effectiveness of DOI. Research data on the mental and physiological responses produced by humans.

In the more than thirty years since Shulkin first described the composition and effects of DOI PikajarThe statement noted that the DEA only counted 40 drug seizures and had “no reported evidence” indicating “whether or how the seized DOIs were used or abused.” When assessing a DOI’s “potential for abuse,” the DEA “does not distinguish between use and abuse.”

The statement said that under the Controlled Substances Act, “the access of manufacturers, distributors, dispensers and researchers to psychotropic substances for useful and legitimate medical and scientific purposes” should not be subject to “undue restrictions.” However, “HHS and DEA’s failure to consider the impact that inclusion of DOIs in Schedule I would have on ongoing and future scientific research on DOIs.” Phelps and Rush plan to present testimony from 15 researchers, including a University of Kentucky neuroscientist Tanner Anderson, chemical biologist David Nichols of the University of North Carolina and David Nutt, a neuropsychopharmacologist at Imperial College London, can attest to the difficulties that would arise from listing DOIs and DOCs and the scientific utility of DOCs to Schedule I.

SSDP and Ramos are seeking an administrative recommendation to reach “findings and conclusions” that the DEA “has failed to meet its responsibilities” and demonstrate that the DOI and DOC have a “high potential for abuse.” Among other things, the challenge raises questions about whether treaty obligations can be met without listing hallucinogens in Schedule I, and whether the decision was “arbitrary and capricious” in violation of the Administrative Procedures Law”.

If the SSDP and Ramos do not prevail in the administrative proceedings, they can challenge the scheduling decision in federal court. In the SSDP press release, Rush referred to “recent Supreme Court decisions” that included denials Chevron doctrine. The principle requires judges to respect federal agencies’ “permissible” or “reasonable” interpretations of “ambiguous” statutes. That deference has long been a source of broad leeway for the DEA, which it relies on to defend controversial decisions such as keeping marijuana in Schedule I — a classification the Justice Department recently reconsidered despite the DEA’s objections.