The Los Angeles Zoo announced Wednesday that it has hatched a record-breaking 17 chicks this year using a new method of raising California condors.

A zoo spokesman said all newborn birds will eventually be considered for release into the wild under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s California Condor Rehabilitation Program.

“What we are seeing now are the benefits of the new breeding and husbandry techniques developed and implemented by our team,” Rose Legato, the zoo’s curator of birds, said in a statement. “The results are emerging from the project. More condor chicks ultimately lead to more vultures in the wild.”

Carl Myers, a zoo spokesman, said the breeding California condors live in the zoo’s buildings and are “affectionately referred to as miniature condors” by staff. When the female produces fertilized eggs, the eggs are transferred to an incubator. As hatching approaches, the eggs are placed with surrogate parents capable of raising the chicks.

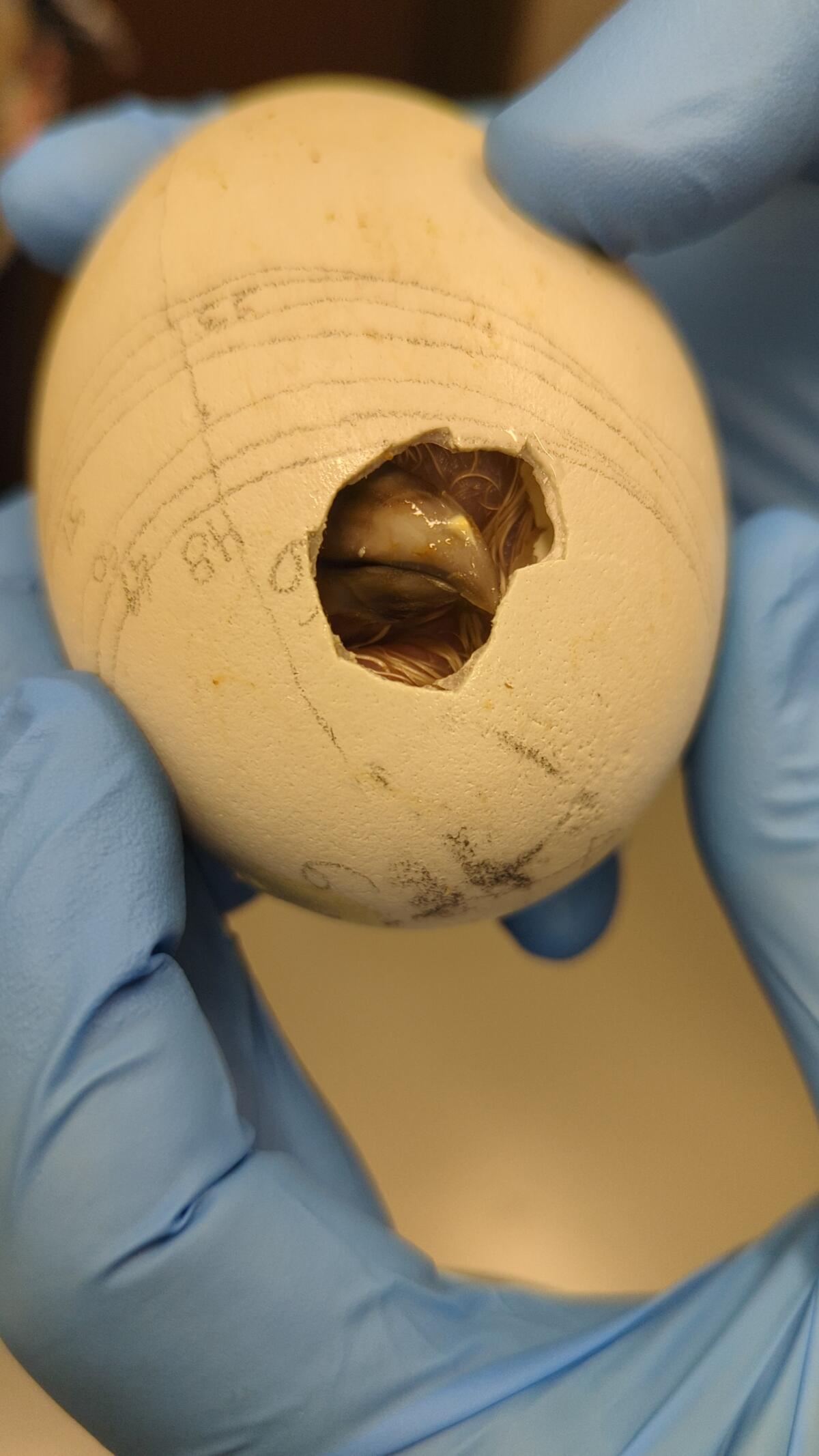

California condor eggs are in the care of the Los Angeles Zoo. The animal is critically endangered.

(Jamie Fan/Los Angeles Zoo)

Good harvest for baby vultures is the result of improved breeding techniques First of its kind at the Los Angeles Zoo.

Previously, when zoos found they had more fertilized eggs than available surrogate adults, staff would hand-raise baby birds. But vultures raised by human caregivers have a lower chance of survival in the wild (so condor puppet Zookeepers used this method in the 1980s to prevent baby birds from imprinting on their human caregivers).

In 2017, the Los Angeles Zoo tried feeding an adult bird named Anyapa two eggs instead of one. The gamble worked. Both birds have been successfully released into the wild.

Faced with this year’s large number of eggs, “the breeders thought, ‘Let’s try three,'” Myers said. “And it worked.”

The zoo’s bald eagle mentors were ultimately able to raise three single-brood chicks, eight double-brood chicks and six triple-brood chicks this season. The previous record was 15 chicks set in 1997.

Vulture experts applaud the new strategy.

“Buzzards are social animals, and we learn more about their social dynamics every year. So I’m not surprised that these chick-rearing techniques are paying off,” said Jonathan Hall, a wildlife ecologist at Eastern Michigan University. (Jonathan C. Hall) said. “I hope chicks raised this way will do well in the wild.”

The California condor is the largest terrestrial bird in North America, with an impressive wingspan of 9.5 feet, and once roamed the continent. Their numbers began to decline in the 19th century as human settlers armed with modern weapons entered the bird’s territory. The scavenger is both hunted by humans and inadvertently poisoned by lead bullet fragments embedded in the carcasses it eats. In 1967, the federal government listed these birds as an endangered species.

One of the zoo’s record-breaking 17 condors emerges from its shell.

(Jamie Fan/Los Angeles Zoo)

Forty years ago, when the California condor recovery program began, there were only 22 California condors left on the planet. As of December, there are 561 individuals in existence, of which 344 are in the wild. Although the program succeeded in increasing the population, the species remains critically endangered.

In addition to the ongoing threat of lead poisoning, large birds are also at risk from other toxins. A 2022 study found more than 40 DDT-related compounds In the blood of wild California condors—these chemicals make their way to the top of the food chain from contaminated marine life.

“Despite our success in returning condors to the wild, free-flying condors still face many obstacles, with lead poisoning being the leading cause of death,” said Joanna Gilkerson, Fish and Wildlife Pacific Southwest Region spokesperson. Gilkeson said. “Innovative strategies, like the one being implemented at the Los Angeles Zoo, help us produce more healthy chicks and continue to release condors into the wild.”

The chicks will remain in the zoo’s care for the next year and a half before being evaluated for release into the wild. So far, the zoo has donated 250 bald eagle chicks to the Fish and Wildlife Program, some of which have been redeployed by the agency to other zoos as part of its conservation efforts.

in a Paper published earlier this yearA team of researchers found that birds raised in captivity had slightly lower survival rates in the first or second year, but then had equally successful outcomes as birds hatched in the wild.

Victoria Bakker, a quantitative ecologist at Montana State University and lead author of the Nature book, said: “Because condors reproduce slowly, releasing captive-bred birds is critical to the species’ recovery, especially “The team at the Los Angeles Zoo should be recognized for their innovative and important contributions to condor recovery. “