Getty Images

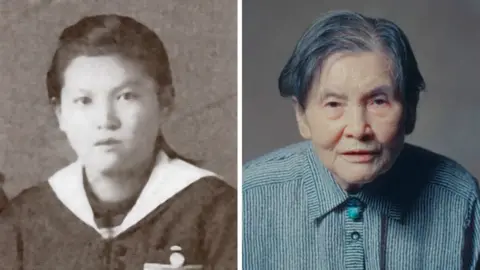

Getty ImagesAlthough it was still early, it was already very hot. Kiraki Chieko wiped the sweat from her forehead while looking for shade. When she did, there was a blinding light – something the 15-year-old girl had never experienced before. It was 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945.

“It felt like the sun was setting – I felt dizzy,” she recalled.

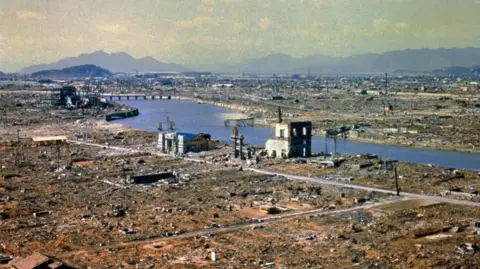

The United States had just dropped an atomic bomb on Chieko’s hometown of Hiroshima—the first time nuclear weapons were used in war. While Germany surrendered in Europe, the Allies in World War II were still at war with Japan.

WARNING: This article contains graphic content that some readers may find disturbing

Chieko was a student but, like many upperclassmen, was sent to work in factories during the war. Carrying an injured friend on her back, she staggered toward school. Many students were severely burned. She applied old oil she found in the home economics classroom to their wounds.

“This is the only treatment we can give them. They are dying one by one,” Chieko said.

“We, the surviving senior students, dug a hole in the playground under the guidance of our teachers, and then I was cremated. [my classmates] With my own hands. I feel very sad for them.

Chieko is now 94 years old. Nearly 80 years since the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, time is running out for surviving victims, known in Japan as atomic bomb survivors, to tell their stories.

Many people faced health problems, lost loved ones and suffered discrimination as a result of the atomic bomb attacks. Now they are sharing their experiences for a BBC Two film, documenting the past in order to serve as a warning for the future.

BBC/Minnow Films/Chieko Kiraki

BBC/Minnow Films/Chieko KirakiChieko said that after the grief, a new life began to return to her city.

“People say grass won’t grow in 75 years,” she said, “but by the next spring, the sparrows are back.”

Chieko said that she had been close to death many times throughout her life, but she came to believe that there was some great force that kept her alive.

Most of the atomic bomb survivors alive today were children when the explosion occurred. As atomic bomb survivors (literally “those affected by the bomb”) age, global conflicts intensify. For them, the risk of nuclear escalation is more real than ever.

“My body was shaking and tears came to my eyes,” said Michiko Kodama, 86, thinking of conflicts around the world today, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Gaza war.

“We must never let the hell of the atomic bomb happen again. I have a sense of crisis.

Michiko, a passionate advocate for nuclear disarmament, said she spoke out so the voices of the victims could be heard and their testimonies passed on to the next generation.

“I think it’s important to hear first-hand accounts from atomic bomb survivors who experienced direct explosions,” she said.

BBC/Minnow Films

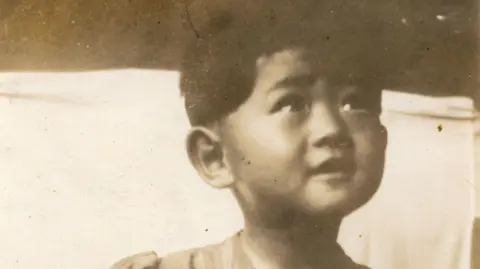

BBC/Minnow FilmsMichiko was seven years old and in school when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

“Through the classroom window, there is a strong light coming to us. It has yellow, orange, and silver colors.

She described how windows in the classroom shattered – pieces flying everywhere and “piercing the walls, tables, chairs”.

“The ceiling collapsed. So I hid my body under the table.

After the explosion, Michiko looked around the destroyed room. From every direction she could see hands and legs trapped.

“I crawled from the classroom into the hallway and my friends were saying to me, ‘Help me.'”

When her father came to pick her up, he carried her home.

Michiko said the black rain fell from the sky “like dirt.” It is a mixture of radioactive material and explosion residue.

BBC/Minnow Films/Michiko Kodama

BBC/Minnow Films/Michiko KodamaShe could never forget her way home.

“It was a hellish scene,” Michiko said. “Those who fled towards us had most of their clothes burned and their flesh melting.”

She remembers seeing a girl – alone – about her age. She was badly burned.

“But her eyes were wide open,” Michiko said. “That girl’s eyes still hurt me. I can’t forget her. Even though 78 years have passed, she is deeply imprinted in my mind and soul.

If her family had stayed back home, Michiko wouldn’t be alive today. It is only 350m (0.21 miles) from the bomb explosion site. Her family moved to a house a few kilometers away about 20 days ago, but this saved her life.

The death toll in Hiroshima was estimated at around 140,000 by the end of 1945.

Three days later, Nagasaki was bombed by the United States, killing at least 74,000 people.

Sueichi Kido lives just 2 kilometers (1.24 miles) from the center of the Nagasaki explosion. He was five years old at the time and suffered partial burns to his face. His mother was more seriously injured, protecting him from the full impact of the blast.

Suichi, 83, recently traveled to New York to speak at the United Nations, warning of the dangers of nuclear weapons.

When he woke up after being knocked out by the explosion, the first thing he remembered seeing was a red oil can. For years, he believed the tank was responsible for the explosion and surrounding damage.

His parents didn’t correct him, choosing to protect him from a nuclear attack – but they cried every time he mentioned it.

BBC/Minnow Films

BBC/Minnow FilmsNot all injuries are immediately apparent. In the weeks and months after the explosion, many people in both cities began to experience symptoms of radiation poisoning, and rates of leukemia and cancer increased.

For years, survivors have faced discrimination in society, especially when it comes to finding a partner.

“I was told, ‘We don’t want the blood of atomic bomb survivors to come into our family,'” Michiko said.

But she did get married and have two children.

She lost her mother, father and brother to cancer. Her daughter died of the disease in 2011.

“I felt alone, angry and scared, and I wondered if it would be my turn next,” she said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnother atomic bomb survivor, Kiyomi Iguro, was 19 when the bomb hit Nagasaki. She describes marrying into a distant relative’s family and having a miscarriage – which her mother-in-law attributed to the atomic bomb.

“‘You have a scary future.’ That’s what she told me.

Kiyomi said she was instructed not to tell her neighbors that she had experienced the atomic bombing.

BBC/Minnow Films/Iguro Kiyomi

BBC/Minnow Films/Iguro KiyomiSince being interviewed for the documentary, Kiyomi has sadly passed away.

But until she was 98, she would visit Nagasaki’s Peace Park and ring the bell at 11:02 (the time the atomic bomb hit Nagasaki) to pray for peace.

BBC/Minnow Films

BBC/Minnow FilmsSuichi continued to teach Japanese history at the university. He said knowing he was a atomic bomb survivor cast a shadow over his identity. But then he realizes he’s not a normal person and feels it’s his duty to speak out and save humanity.

“I had a feeling inside that I was a special person,” Mo Yi said.

This is something all atomic bomb survivors feel in common – an abiding determination to ensure that the past never becomes the present.

Atomic Man It will be broadcast on BBC Two and BBC iPlayer on Wednesday 31 July.

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this article, you can get support and advice in the following ways: BBC Action Line.