disney

disney“I may be good, but I’m not a hero.”

In Deadpool’s own words, he’s “just a bad guy who gets paid” to annoy “worse people.”

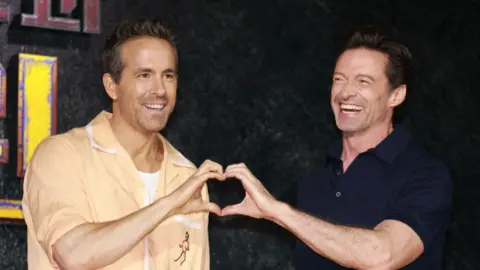

Ryan Reynolds’ character in “Deadpool and Wolverine,” the third installment of the Marvel series released this week, is far from the only antihero to win over fans in recent years.

They are often morally ambiguous characters, neither superheroes nor villains.

Take Wanda Maximoff (Scarlet Witch), who will go to great lengths to build a family, including taking an entire community hostage in the 2021 episode of WandaVision.

Later this year, the villain-turned-antihero movie “Venom” will return to the big screen for a third time as a journalist who will stop at nothing to protect the innocent.

Deadpool, aka Wade Wilson, gained immortality after participating in an experimental program to cure cancer, but things went wrong and he was left to die, leading him to embark on a path of revenge and kill his betrayers.

But what about these characters of murder and mayhem that some people can relate to more than superheroes?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesComics fan Chelsea-Lee Nolan, 26, from Kent, said they were just “more human”.

“No one is completely good or completely evil, so the idea of an antihero is really good,” she said.

It is in these gray areas that Ms. Nolan can see her “element.”

“I’m not perfect and I don’t want to be,” she added. “The idea of a hero who doesn’t make mistakes is anachronistic.”

For Reece Connolly, a 30-year-old writer and performer living in London, antiheroes are more realistic.

“They move towards moral rights, but they also make mistakes, have regrets, have bad habits and personality quirks,” Mr Connolly explained.

In the comic book Deadpool (2008) #45, a group of trafficked women call him a “good guy” after he rescues them, but the mercenary quickly rejects it, saying: “Well… well, yeah – Maybe it’s nice to be a part of me sometimes, but like the rest of me, well…”

His reluctance to be called a “good guy” is an admission of his flaws.

Deadpool, the self-proclaimed “mercenary with a mouth,” has a loud, ferocious and maddening voice, all things a superhero is not.

Rhys Connolly

Rhys ConnollyOther antiheroes have similar characteristics. Loki, played by Tom Hiddleston, is a villain who gradually becomes a man trying to do the right thing, albeit with a hint of trickster mischief thrown in for good measure.

Dara Greenwood of New York’s Vassar College, who has spent a lot of time studying these characters, says the “dark side” that antiheroes embrace plays a huge role in their appeal.

“[They] provides us with an imaginative opportunity to gain insight into the ‘dark side’ of human behavior in a way that is free from repercussions or blame,” said Associate Professor of Psychological Science.

This may lend some support to the affective disposition theory, which suggests that people enjoy entertainment more when a character they like succeeds and a character they don’t like fails.

A defining part of Deadpool is his humor. He is known for his ability to “throw out the crazy witty science” (quips and innuendos, as he calls them) – often at the most inappropriate times.

Professor Greenwood said when violence is combined with humour, it can be seen as funny rather than toxic, which can make us “desensitized” to its brutality.

disney

disneyMany superheroes see their powers as a call to do good—superheroes like Spider-Man remain fan favorites who show resilience in the face of hardship and continue to save people instead of harming them.

But Deadpool knows he’s a fictional character who exists to please others and constantly breaks the fourth wall to talk to readers and viewers. A 2019 study showed that this rapport gives us the same sense of attachment and intimacy as a personal relationship.

Ms Nolan said it made her feel “involved”, while Mr Connolly likened it to “conversations, secrets or jokes we are told”.

For him, antiheroes like Deadpool are “heroes who retain all the fun parts.”

“Chaos, weirdness, flaws,” he said.