University College London

University College LondonA group of remote Scottish islands may help solve one of the biggest mysteries on Earth, scientists say.

Researchers have found that the Gaverach Islands off the west coast of Scotland provide the best record of Earth entering the largest ice age on record about 720 million years ago.

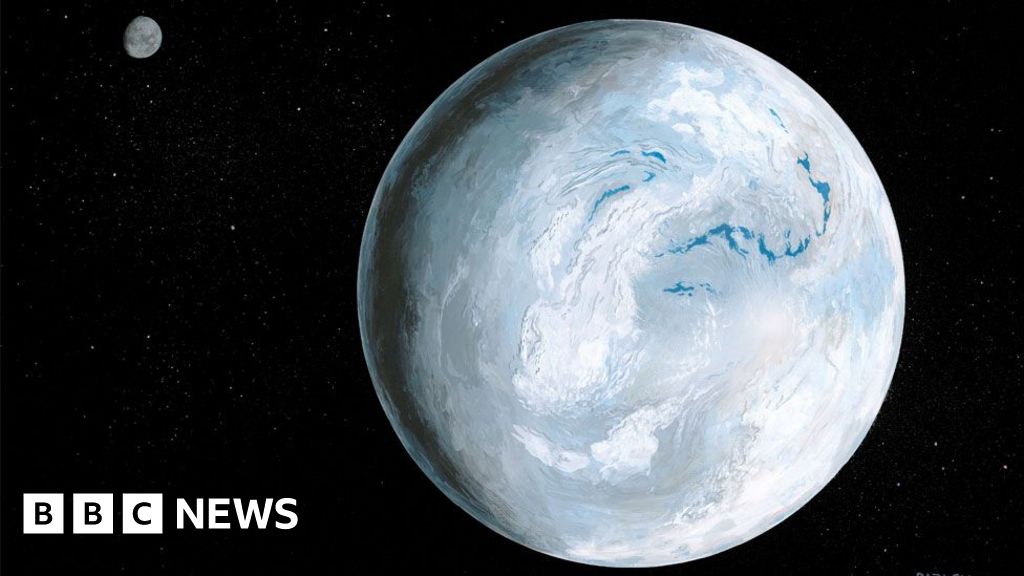

This great freeze covered almost the entire earth in two stages and lasted for 80 million years. It was called “Snowball Earth”, after which the first animal life appeared.

Clues about the ice hidden in the rocks have disappeared everywhere – except in the Gavilach Mountains. Researchers hope the islands will tell us why the Earth entered such an extreme freezing state for such a long time, and why it was necessary for the emergence of complex life.

sound pressure level

sound pressure levelRock layers can be thought of as a history book – each layer contains detailed information about Earth’s conditions in the distant past.

But the critical period of Snowball Earth is thought to be missing because the rock formations were eroded by the Big Freeze.

Now, a new study by researchers at University College London suggests that the Gavilaches somehow escaped unscathed. It may be the only place on Earth that has detailed records of how the Earth entered one of the most catastrophic periods in its history, and what happened hundreds of millions of years ago when the snowballs melted and the first animal life emerged.

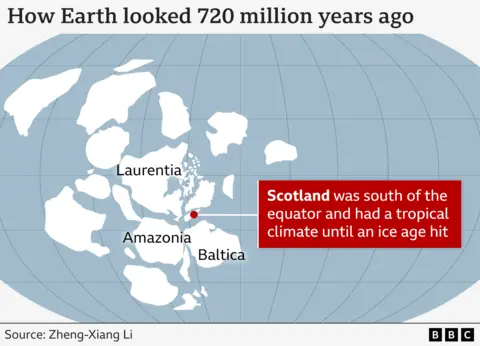

Scotland was in a completely different place at the time because the continent had moved over time. It is located south of the Earth’s equator and had a tropical climate until it and the rest of the Earth were engulfed in ice and snow.

Graham Shields, a professor at University College London who led the research, told BBC News: “We captured the moment when Scotland entered the Ice Age, which was the moment that no other place in the world did. No.

“Millions of key years are missing elsewhere due to glacial erosion, but these are present in the rock formations of the Gavilach Mountains.”

The islands of Scotland’s Inner Hebrides are uninhabited except for a team of scientists working in a solitary building on the main island, but there are also the ruins of a 6th-century Celtic monastery.

This breakthrough was achieved by Professor Shield’s doctoral student Elias Rugen, whose research results were published in the Journal of the Geological Society of London. Elias was the first to date the rock formation and identify it as a critical period missing from all other rock formations from other parts of the world.

His discovery earned the Gavilaghers one of science’s greatest honors: hammering a golden nail at the site considered the best record of a planet-altering geological moment—although, to deter thieves, the nails were actually Not made of gold.

University College London

University College LondonElias took many of the Golden Nail’s judges (officially known as members of the “Cryogenics Subcommittee”) to the rock face multiple times to make his case.

The next stage is to allow the wider geological community to raise any objections or come up with better candidates. If not, then there could be a spike next year.

The award will raise the scientific profile of the site and attract further research funding.