Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition“There’s no room for error,” Isak Rockström said. “We’re in a position now where the only help we can get is from a few Canadian Coast Guard icebreakers that patrol throughout the Canadian Arctic.”

For the past two months, 26-year-old Isak and his 25-year-old brother Alex have braved the freezing temperatures of the Arctic Circle.

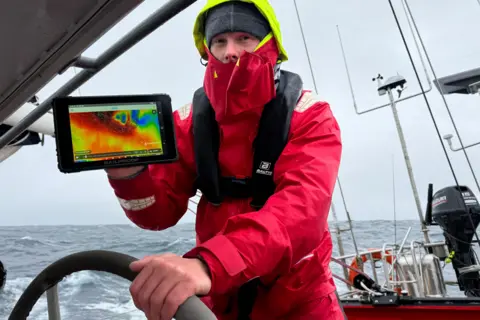

They sail through the dangerous and sometimes unfamiliar landscape of the Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, collecting the latest data on climate change in the region.

They encountered icebergs and strong winds around Iceland.

As Isaac stoically puts it, a “tricky situation” arose the day before their BBC interview. While sailing through the fjord, they were blown toward the coast by 52 mph (84 km/h) winds from nearby mountains.

“The wind was so strong and the engine was on, we couldn’t go anywhere,” he recalled.

Near Devon Island, the largest uninhabited island in the world, they risked becoming stranded due to poor mapping of the area.

Alex said they had to quickly turn the other sails so the wind was in their favor and “take some things apart and cut some corners” to get the mainsail down.

But Isaac said “the most challenging ocean crossing of my life” was the long journey across the Davis Strait through thick fog and ice around Greenland.

He said it felt like they were “trudging… in heavy wind or fog.”

“Then one day the fog cleared a little and there was a little tunnel through the clouds in the distance – and we finally actually saw Greenland. It was great confirmation that we weren’t crazy.”

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific ExpeditionOnly a handful of crews make it through the passage each year, and these brothers are among the youngest crews ever to attempt it.

The BBC caught up with them on the trip as they approached one of the most challenging sections of the trail – one they both feared and looked forward to.

Since setting sail from Norway in June, the Abel Tasman’s crew has sailed around Iceland and Greenland before entering the rough waters between Canada’s far north and the Arctic.

They hope to reach the finish line in Nome, Alaska, in early October.

Skipper Isak is one year older than Canadian Jeff MacInnis when he completed the passage in 1988 at age 25. people.

But they are experienced sailors – they sailed from Stockholm, Sweden to the west coast of Mexico in 2019.

As captain and first mate, they say sailing the 75-foot schooner has only strengthened their brotherhood and that their little expedition is like an adopted family.

“I don’t think we’ll get any closer than we are now,” Isaac said.

Alex added: “I think we do understand how each other operates and we don’t step on each other’s toes.”

Alex said he had long wanted to travel through the Northwest Passage, despite the dangers of the journey. He was interested in maps of the area and stories of previous expeditions, and realized that the area might be transformed by climate change.

He recalls sailing off the coast of Greenland one night, something he says will stay with him for the rest of his life.

“We were slowly crossing the huge iceberg under the midnight sun, and it was incredible when the light hit the iceberg… It was so beautiful.”

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific ExpeditionIsak took a few more convincing steps before heading out. What convinced him, he said, was that “this was one of the few expeditions that was truly adventurous,” with its mix of danger and isolation.

The expedition’s general leader, Keith Tuffley, who quit his job at Citibank to join the expedition and owns the Abel Tasman, has become something of an agent for Rockströms Father.

The Rockstroms’ real father, Johan, is a Swedish climate scientist who helped develop the concept of climate tipping points, in which specific large-scale environmental changes are thought to become self-perpetuating and irreversible after exceeding a certain threshold.

Part of the purpose of this expedition is to highlight how climate change is increasing the risk of reaching these tipping points, particularly for some systems in the Arctic Circle.

Multiple studies have shown that if global warming reaches 1.5-2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, parts of the Greenland ice sheet will become more susceptible to uncontrolled melting. However, the precise location of such a tipping point is highly uncertain, and full collapse could take thousands of years.

The Rockströms lived on the Abel Tasman, balancing study and adventure while studying climate physics at the University of Bergen.

While much of the data they collect must be sent back to the lab for analysis, Alex says the raw data from the seawater measurements they’ve taken suggest the waters around Greenland are colder and less saline than before – This is a sign that the ice caps are melting.

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific ExpeditionProfessor David Sonali, a marine and climate scientist at University College London, explained that over time, the influx of freshwater from the Greenland ice sheet could weaken the transatlantic mainstream and have a negative impact on the climate.

Melting ice caps are also causing global sea levels to rise, increasing the risk of coastal flooding.

Professor Sonali said that ice melting may not only affect the balance of the marine ecosystem, but may also produce a feedback process. “Melting water will cause changes in ocean circulation, causing warm seawater to reach the glaciers that flow into the ocean, which in turn will lead to faster seawater flow.” “The melting and retreat of glaciers”.

Alex hopes the data they collect along the Northwest Passage will be significant.

“I think it’s easy to underestimate the value of data collected from a sailboat like this… Big ships, big icebreakers, they’re very limited in where they can go.”

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific Expedition

Northwest Passage Marine Scientific ExpeditionThe crew of the Abel Tasman still have a long and challenging road ahead of them.

“Where we are now is one of those points in the journey where, from day one, we’re a little worried but looking forward to it hopefully because this is…the beginning of the really challenging part,” Isaac said.

Expedition leader Tafley said that while melting Arctic ice makes it easier for ships to pass through the Northwest Passage, the icebergs created by the process make the journey more “unpredictable.”

Sometimes their surroundings seem completely alien.

“It looks like Mars,” Keith said of Devon Island, where they anchored.

“It’s wild and rugged. It has a reddish ironstone hue.

Apart from a few walruses and polar bears, the crew is completely alone.