Getty Images

Getty ImagesA military alliance between Somalia and Egypt is irritating the fragile Horn of Africa and particularly unnerving Ethiopia – amid fears the consequences could go beyond a war of words.

Tensions increased this week as two Egyptian C-130 military aircraft arrived in the Somali capital Mogadishu, marking the start of an agreement signed during the Somali president’s state visit to Cairo in early August.

The plan is to add up to 5,000 Egyptian soldiers to a new African Union force by the end of the year, with a further 5,000 soldiers reportedly to be deployed separately.

Ethiopia has been a key ally in Somalia’s fight against al-Qaeda-linked militants and is at loggerheads with Egypt over the construction of a massive dam on the Nile.

Somalia’s defense minister hit back, saying Ethiopia should stop “crying” because everyone “will reap the consequences” – a reference to the downward spiral in diplomatic relations between the two countries that has been going on for months.

Why are Ethiopia and Somalia at odds?

It all hinges on the ambition of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who wants the landlocked country to have a port. After Eritrea seceded in the early 1990s, Ethiopia lost its access to the sea.

On New Year’s Day, Mr Abiy signed a controversial deal with the self-proclaimed republic of Somaliland to lease a 20-kilometer (12-mile) stretch of its coastline for 50 years to establish a naval base.

It could also lead to Ethiopia formally recognizing the breakaway republic – something Somaliland is pushing for.

Somaliland broke away from Somalia more than 30 years ago, but Mogadishu considers it part of its territory and described the agreement as an act of “aggression”.

Geopolitical analyst Jonathan Fenton-Harvey told the BBC that Somalia was concerned that the move could set a precedent and encourage other countries to recognize Somaliland’s independence.

Neighboring Djibouti is also concerned it could harm its port-reliant economy, he added, as Ethiopia has traditionally relied on Djibouti for imports.

In fact, in an effort to ease tensions, Djibouti’s foreign minister told the BBC that Djibouti was ready to provide “100%” port use to Ethiopia.

“It will be located in the port of Tadjoura – 100 kilometers [62 miles] Coming from the Ethiopian border,” Mahmoud Ali Yusuf told Africa Television’s BBC Focus program.

A senior presidential adviser said it was definitely a shift from last year.

Turkey’s efforts to calm tensions have so far failed, with Somalia insisting it will not back down until Ethiopia recognizes sovereignty over Somaliland.

Why is Ethiopia so disturbed by Somalia’s response?

Not only has Somalia included its Nile foe Egypt, it has also announced that Ethiopian troops will no longer join AU forces from next January.

This comes as the AU’s third peace support operation begins – the first deployed months after Ethiopian troops crossed the border in 2007 to help fight al-Shabaab Islamist militants who then controlled Somalia’s capital.

Reuters reports that there are currently at least 3,000 Ethiopian soldiers in the African Union Mission.

Last week, Somalia’s prime minister also said Ethiopia would have to withdraw between 5 and 7,000 other troops stationed in various areas under separate bilateral deals – unless it withdraws from a port deal with Somaliland.

Ethiopia sees this as a slap in the face “for the sacrifices Ethiopian soldiers have made for Somalia”, as its foreign minister said.

Christopher Hockney, a senior fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, told the BBC that withdrawing troops would also leave Ethiopia vulnerable to jihadist attacks.

He added that Egypt’s plans to deploy troops along its eastern border would also be of particular concern to Ethiopia.

Egypt views Ethiopia’s western Nile dam as an existential threat and has warned it will take “measures” if its security is threatened.

Why are Nile dams so controversial?

Egypt accuses Ethiopia of threatening its water supply by building the Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Gerd).

The work began in 2011 on a tributary of the Blue Nile in the highlands of northwestern Ethiopia, where 85% of the Nile’s water comes from.

Egypt said Ethiopia was advancing the project with “complete disregard” for the interests and rights of downstream countries and their water security.

It also believes that a 2% reduction in the Nile’s flow could result in the loss of about 200,000 acres (81,000 hectares) of irrigated land.

For Ethiopia, the dam is seen as a way to revolutionize the country, providing electricity to 60% of the population and a steady flow of electricity to businesses.

The latest diplomatic efforts to determine how the dam would operate and determine how much water would flow downstream to Sudan and Egypt failed in December.

How worried should we be?

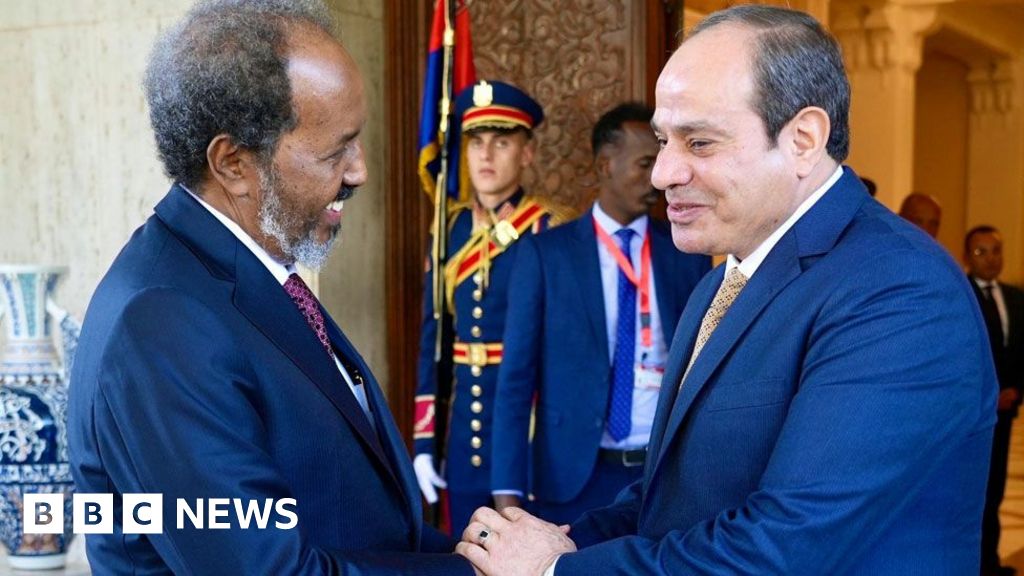

Egypt considers the military agreement with Somalia “historic” – in the words of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi – and possibly an opportunity to settle scores over the massive dam.

Dr. Hassan Kanej, director of the Horn Institute for International and Strategic Studies, warned that the Nile dispute was, in fact, likely to unfold in Somalia.

If Ethiopian and Egyptian troops meet on the Somali border, it could lead to a “small-scale inter-state conflict” between Ethiopia and Egypt.

Somaliland also warned that Egypt’s establishment of military bases in Somalia could destabilize the region.

Both Ethiopia and Somalia are already dealing with their own internal conflicts – Ethiopia has small-scale rebellions in several areas, while Somalia is recovering from three decades of devastating civil war and still needs Confronting Al-Shabaab.

Experts say neither side can afford further war and more unrest will inevitably lead to more migration.

Dr Kananje told the BBC that if a conflict breaks out, it could attract other players, further complicating Red Sea geopolitics and further affecting global trade.

According to shipping monitor Lloyd’s List, at least 17,000 ships pass through the Suez Canal each year, meaning 12% of global trade passes through the Red Sea each year, with cargo worth $1tn (£842bn).

As a result, countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Turkey have been keen to build partnerships with African countries on the Red Sea coast, such as Somalia.

Mr Harvey said Türkiye and the UAE were more likely to mediate and find a middle ground.

The UAE has invested heavily in the port of Berbera in Somaliland and has significant influence over Ethiopia as a result of its investment.

All eyes will be on Turkey, which has ties to both Ethiopia and Somalia, the next steps in its diplomatic efforts. Talks are scheduled to begin in mid-September.

Additional reporting by Ashley Lime, Waihiga Mwaura, Chalkidan Yibeltal and Juneydi Farah

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC