BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonWARNING: This story contains distressing details from the beginning.

“This is like the end of the world for me. I feel so sad. Can you imagine what I went through watching my children die?” Amina said.

She lost six children. None of them survived past the age of three, and the other is now fighting for his life.

Seven-month-old Bibi Hajira is the size of a newborn. She suffers from severe acute malnutrition and takes up half a bed in her ward at Jalalabad District Hospital in Nangarhar province, eastern Afghanistan.

“My children died of poverty. I could only feed them dry bread and water heated in the sun,” Amina said, almost shouting in pain.

What’s even more devastating is that her story is far from unique – many more lives could have been saved if treated promptly.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonBibi Hajira is one of 3.2 million children across the country suffering from severe malnutrition. The situation has plagued Afghanistan for decades, triggered by four decades of war, extreme poverty and three years since the Taliban took over.

But now the situation has reached an unprecedented cliff.

It is difficult for anyone to imagine what 3.2 million people must be like, so the story of what happened in just one small ward can help provide insight into the catastrophe that is unfolding.

There are 18 young children in seven beds. This is not a seasonal surge, but a day-in and day-out situation. There were no cries or gurglings, and the unsettling silence in the room was broken only by the high-pitched beep of the pulse monitor.

Most of the children were not sedated or put on oxygen masks. They were awake but too weak to move or make a sound.

Sleeping in the same bed as Bibi Hajira is three-year-old Sana, wearing a purple coat and covering her face with her little arms. Her mother died a few months ago while giving birth to her sister, so her aunt Leila took care of her. Laila touched my arm and held up seven fingers—one for each child she lost.

On the bed next to him lay three-year-old Ilham, too small for his age, with skin peeling off his arms, legs and face. Three years ago, his two-year-old sister died.

It was too painful to even look at one-year-old Asma. She had beautiful hazel eyes with long eyelashes, but they were wide open and barely blinking because her oxygen mask covered most of her little face.

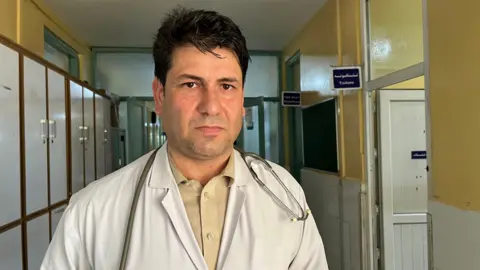

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonDr. Sikandar Ghani, standing next to her, shook his head. “I didn’t think she was going to survive,” he said. Asma’s petite body was already in sensitivity shock.

Despite the circumstances, there had been a sense of stoicism in the room until then – nurses and mothers continuing to work, feeding their children and comforting them. Everything stopped, and many people had broken expressions on their faces.

Asma’s mother Naseeba is crying. She lifted her veil and leaned over to kiss her daughter.

“It feels like the flesh is melting from my body. I can’t bear to see her suffering like this. Nasiba has lost three children. “My husband is a worker. When he goes to work, we eat .

Dr. Ghani told us that Asma could go into cardiac arrest at any time. We leave the room. She died less than an hour later.

The Taliban Public Health Department in Nangarhar Province told us that 700 children have died in hospitals over the past six months, with the death toll exceeding three a day. This is a staggering number, but if this facility did not have funding from the World Bank and UNICEF to keep it running, the death toll would be much higher.

As of August 2021, international funds provided directly to the previous government funded nearly all public health care in Afghanistan.

The funding was stopped due to international sanctions imposed on them after the Taliban took over. This triggered a health care collapse. Aid agencies stepped in to provide temporary emergency response measures.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonThis has been an unsustainable solution, and now, in a world distracted by too many other things, funding for Afghanistan has dwindled. Likewise, Taliban government policies, particularly restrictions on women, mean donors are hesitant to provide funding.

“We have inherited problems of poverty and malnutrition, which have become worse due to natural disasters such as floods and climate change. The international community should increase humanitarian aid and should not link it to political and internal problems.

We have been to more than a dozen medical facilities across the country over the past three years and have seen the situation rapidly deteriorate. During our past few visits to the hospital, we have witnessed children die.

But we also see evidence that the right treatment can save children. Dr. Ghani told us on the phone that Bibi Hajira was in a very weak condition when we went to the hospital, but is now much better and has been discharged.

“If we had more medicines, facilities and staff, we could save more children. Our staff have a deep commitment. We work tirelessly and are prepared to do more.

“I have children too. We suffer too when our children die. I know what parents must be thinking.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonMalnutrition is not the only cause of the surge in mortality. Other preventable and curable diseases are also killing children.

In the intensive care unit next door to the malnutrition ward, six-month-old Umra was battling severe pneumonia. She cried loudly as the nurse dripped saline solution into her body. Nasreen, the mother of Umrah, sat next to her with tears streaming down her face.

“I wish I could die in her place. I’m scared,” she said. Two days after we went to the hospital, Umrah passed away.

These are the stories of those who were taken to the hospital. There are countless people who can’t do it. Only one in five children who require hospitalization can receive treatment at Jalalabad Hospital.

The facility was under such pressure that almost immediately after Asma’s death, a three-month-old baby named Alia was moved into half of Asma’s vacated bed.

No one in the room had time to process what was happening. There is another child who is very sick and needs treatment.

The Jalalabad hospital serves a population of five provinces, estimated by the Taliban government to be around 5 million people. And now it is under even greater pressure. Most of the more than 700,000 Afghan refugees forcibly expelled by Pakistan since late last year continue to remain in Nangarhar.

In the communities surrounding the hospital, we found evidence of another alarming statistic released by the United Nations this year: In Afghanistan, 45 percent of children under five are stunted — shorter than they should be.

Robina’s two-year-old son, Mohammed, cannot yet stand and is much shorter than he should be.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen Anderson“The doctors told me that if he gets treatment within the next three to six months, he will be fine. But we can’t even afford food. How will the treatment be paid for? Robina asked.

She and her family had to leave Pakistan last year and now live in a dusty, dry settlement in the Sheikh Misri district, a short dirt road drive from Jalalabad.

“I was worried that he would become disabled and never be able to walk,” Robina said.

“In Pakistan, our life is also difficult. But there are jobs. My husband is a worker and it is rare to find a job here. If we were still in Pakistan, we could treat him.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonUNICEF says stunting can cause severe, irreversible physical and cognitive damage that can last a lifetime and even affect the next generation.

“Afghanistan’s economy is already in trouble. If a large proportion of our next generation have physical or mental disabilities, how will our society help them? Dr. Ghani asked.

If Muhammad had received treatment before it was too late, he could have been spared permanent damage.

But community nutrition programs run by Afghanistan’s aid agencies have seen the biggest cuts – with many receiving only a quarter of the funding they need.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonIn alley after alley in Sheikh Misri, we met families with children who were malnourished or stunted.

Sardar Gul, who has two malnourished children – three-year-old Omar and eight-month-old Mujib – holds a bright-eyed little boy on his lap.

“A month ago, Mujib’s weight had dropped to less than three kilograms. As soon as we were able to register him with the aid agency, we started receiving food packets. These really helped him,” said Sardar Gul.

Mujib now weighs 6kg, which is still a few kilos less, but a significant improvement.

There is evidence that prompt intervention can help children avoid death and disability.

Additional reporting: Imogen Anderson and Sanjay Ganguly