The Supreme Court on Monday rejected an appeal by California prison officials who sought immunity from lawsuits after they transferred inmates with COVID-19 to San Quentin in May 2020, sparking a dispute that killed 26 inmates and one Epidemic of prison guard deaths.

The judge dismissed the appeal without comment or dissent.

The transfer decision was later lambasted by state lawmakers as a “miserable failure,” “an abomination” and “the worst prison health problem in state history.”

California Men’s College in Chino has been hit hard by COVID-19. In May 2020, nine inmates at the prison died and about 600 were infected.

San Quentin had no known cases at the time. To prevent further harm from CIM, prison officials decided to move 122 inmates from north Chino to San Quentin.

Within days, San Quentin reported 25 COVID-19 cases among 122 new arrivals. Within three weeks, the virus spread to 499 more people.

As of early September, at least 2,100 inmates and 270 staff members had tested positive.

The state is currently facing four major lawsuits from families of the deceased as well as inmates and staff who were infected but survived.

The lawsuits can now move forward because California federal courts and the Supreme Court have rejected the state’s argument that prison officials have “qualified immunity” that protects them from prosecution.

“The state has had due process all the way up to the Supreme Court. They will not give up on a technicality,” the families’ attorney, Michael J. Haddad, said in response to the court order. “It’s time to face the facts. Prison administrators killed 29 people in what the 9th Circuit called a ‘textbook case’ of willful indifference.”

The defense of qualified immunity often shields police officers from lawsuits. The judges said police and other government officials could be prosecuted for violating individuals’ constitutional rights, but only if they intentionally violated “clearly defined” rights.

The court said police often have to make split-second decisions, such as whether a suspect being pursued is armed with a gun. Thus, if an officer shoots a fleeing man under the mistaken belief that the suspect is armed, courts sometimes protect the officer from prosecution for “unreasonable seizure.”

Lawyers for the families said the pending prison cases are significantly different because prison officials decided to make the transfer without taking the precautions they thought were needed at the time.

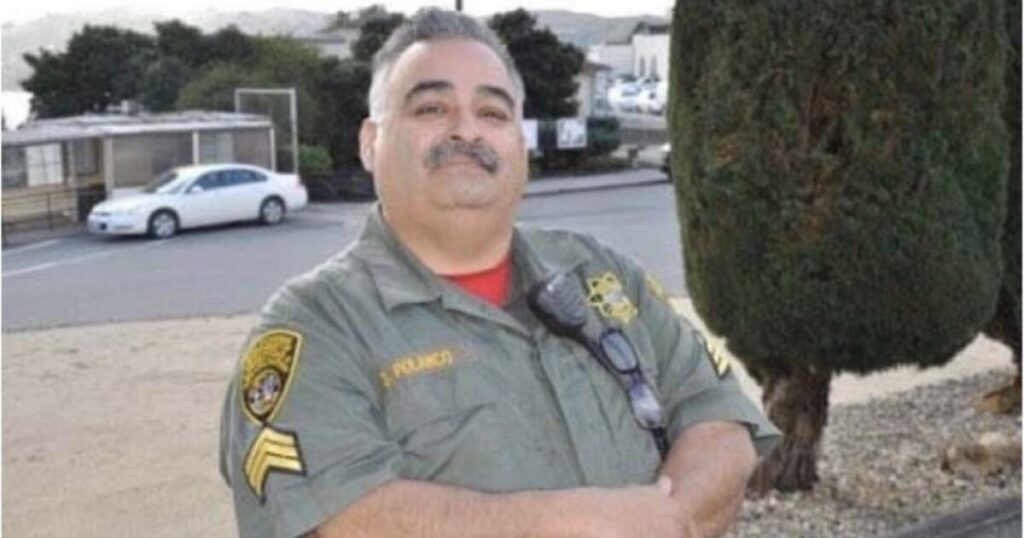

Sgt. Death guard Gilbert Polanco, 55, has worked at San Quentin for more than two decades. He has multiple health conditions, including obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure, putting him at high risk if he contracts COVID-19.

His duties during the pandemic included driving sick inmates to local hospitals, but attorneys said prison officials refused to provide him or the inmates with personal protective equipment.

He contracted COVID-19 in late June 2020 and died in August after a lengthy hospitalization.

In Polanco’s case, the lawsuit says he died due to a “state-created danger.”

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said prison officials did expose Polanco to dangers he would not otherwise have faced and failed to take steps to protect him from the dangers they posed.

The Supreme Court has also ruled in the past that prisoners are entitled to protection from “unnecessary and wanton infliction of suffering,” including “deliberate indifference to their serious medical needs.” Lawyers for San Quentin inmates said prison officials could be held liable under that standard.

California prosecutors are urging the Supreme Court to review and overturn the Ninth Circuit’s decision to reject a prison officer’s qualified immunity defense.

“The facts of these cases are undoubtedly tragic,” they said. But in the “early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when little was known about the disease and testing supplies were limited, the defendant officers tried to protect those incarcerated. “The lives of dozens of vulnerable prisoners in virus-ridden prisons.”

With the benefit of hindsight, they agree their actions may have been judged wrong, but “there was no clear law that brought them to attention that their allegations of mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic at San Quentin Prison were unconstitutional.”