The prosecutor’s job is to hold the public accountable. But paradoxically, when the situation is reversed—when the prosecutor is the one suspected of flouting the law—it becomes extremely difficult for victims to obtain recourse. Lawyers squabbled in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit yesterday over a roadblock that would prevent someone from prosecuting a former assistant district attorney who is accused of misconduct to the point where a 5th Circuit judge Last year called it “completely crazy”.

At the center of the case is Ralph Petty, whose multi-year career included serving as an assistant district attorney and law clerk while working for the same judge. In practice, this meant that his arguments as a prosecutor were sometimes performance art because, as a law clerk, he had the opportunity to draft the same rulings he sought in court. It doesn’t take a lawyer to deduce that this setting would have troubling implications for due process.

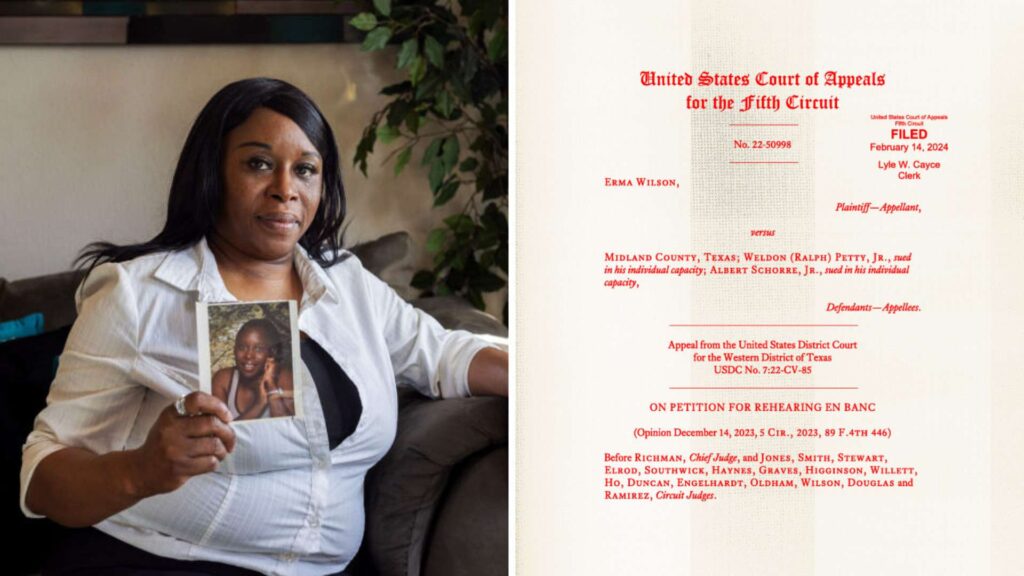

One of Petty’s victims, Elma Wilson, wants a chance to file a civil lawsuit against Petty in front of a jury. She was convicted of cocaine possession in 2001 after police found a bag of cocaine on the ground near where she and some friends had gathered. If she implicates a guilty party, law enforcement will let her off the hook. She said she didn’t know.

Years later, this belief still haunts her. Most notably, it doomed her chances of realizing her lifelong dream of becoming a nurse because the state of Texas, where she lived, did not approve RN licenses for people convicted of drug-related crimes.

At the same time as Wilson was convicted, Petty began working double duty in Midland County, Texas.Although he was not the lead prosecutor in her case, she claim He “communicated with and provided advice to other prosecutors in the District Attorney’s Office” regarding her prosecution, while working for Judge John G. Hyde, who presided over her case, giving him “access to documents that prosecutors generally do not have access to and information”. (Hyde died in 2012.

“Judges Petty and Hyde participated in further undermining confidence in the criminal prosecution of Elma unilateral Communications Regarding Irma’s Case,” Her Lawsuit read. “Subsequent motions, such as Elma’s motion to suppress, were resolved in the prosecution’s favor throughout the trial. Despite insufficient evidence, Elma’s motion for a new trial was not granted. Any of these facts alone All undermine the integrity of the Elma trial…these facts taken together prove this.

Typically, prosecutors are protected by absolute immunity, which, as the name implies, is a more powerful shield than qualified immunity. But the issue is not before the 5th Circuit, because Wilson must overcome another hurdle: People convicted of a crime are barred from suing under Section 1983 — the federal statute that allows lawsuits against alleged constitutional violations by state and local government employees — Unless “the conviction or sentence has been quashed on appeal or otherwise invalidated,” wrote In December, 5th Circuit Judge Don Willett. “The problem here is that Petty’s conflicting double-hat arrangement was only exposed back Wilson has completed his sentence.

But Willett – the judge who described Petty’s alleged malfeasance as “completely insane” – seemed unsatisfied with his ruling, saying that was because precedent tied his hands. He invited the en banc 5th Circuit to hear the case, where all the judges on the court come together to reconsider the appeal, rather than a three-judge panel (the usual format for evaluating a case).

The court accepted. “The defendant said [Wilson is] Invoking this or any other federal cause of action is forever barred unless she first persuades state officials to grant her relief. If they didn’t, she would never have been able to bring the case,” Institute of Justice lawyer Jaba Tsitsuashvili, who represents Wilson, argued yesterday. “In most circuit courts, this argument would be rejected, and rightly so.

The center of the case is Heck v. Humphrey (1994), as Willett points out, Supreme Court precedent eliminates Section 1983 relief for plaintiffs alleging unconstitutional convictions if their criminal cases are not resolved with a “favorable termination.”The problem is: Most federal appeals courts have determined oops This provision does not apply when the federal writ of habeas corpus no longer applies, which was the case in Wilson. The Fifth Circuit is an exception.

Maybe not any time soon. Yet even if the justices agreed with Tsitsouashvili’s interpretation of the law, Wilson didn’t know. She must then explain why Petty is not entitled to absolute immunity, which shields prosecutors from such civil lawsuits if their alleged misconduct was committed within the scope of their prosecutorial duties. This is almost impossible to overcome. But Petty may not be that candidate because technically his malfeasance was not committed as a prosecutor. This was committed as a legal clerk.

If Wilson is granted prosecutorial privilege, it would be the first time Petty’s victims have any real chance for recourse. It’s true, of course, that he was disbarred, but that may not be a comfort to those defendants who were harmed by Petty’s trial, especially considering that this is happening in 2021 (two years after his retirement).