Nawab Khan, who lives in Lohta, said weavers like him have become poorer in the past decade.

“The only way to prosper is to be a BJP supporter, otherwise you will be in trouble. Those who buy saris become richer, and those who [predominantly Muslims] People who make them poorer,” he claimed.

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s Dilip Patel, who holds 12 parliamentary seats including Varanasi, dismissed ongoing accusations that Muslims are marginalized or that the government discriminates against them, and said welfare schemes are distributed equitably.

He accused the opposition of “terrifying our Muslim brothers and sisters” before Modi came to power in 2014.

“But since then, they are no longer afraid and their trust in the BJP is growing day by day,” he claimed. He also mentioned that Muslims particularly appreciated the criminalization of “triple talaq”, i.e. “immediate divorce” practice.

However, anti-Muslim hate speech has surged over the past decade as right-wing groups have launched numerous attacks against Muslims, many of them fatal.

“When India and Pakistan were divided, our forefathers rejected Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s [founder of Pakistan] Call and stay in the country. We also gave our blood to build this country. Yet we are treated like second-class citizens,” said Athar Jamal Lari, who campaigned against Modi in Varanasi.

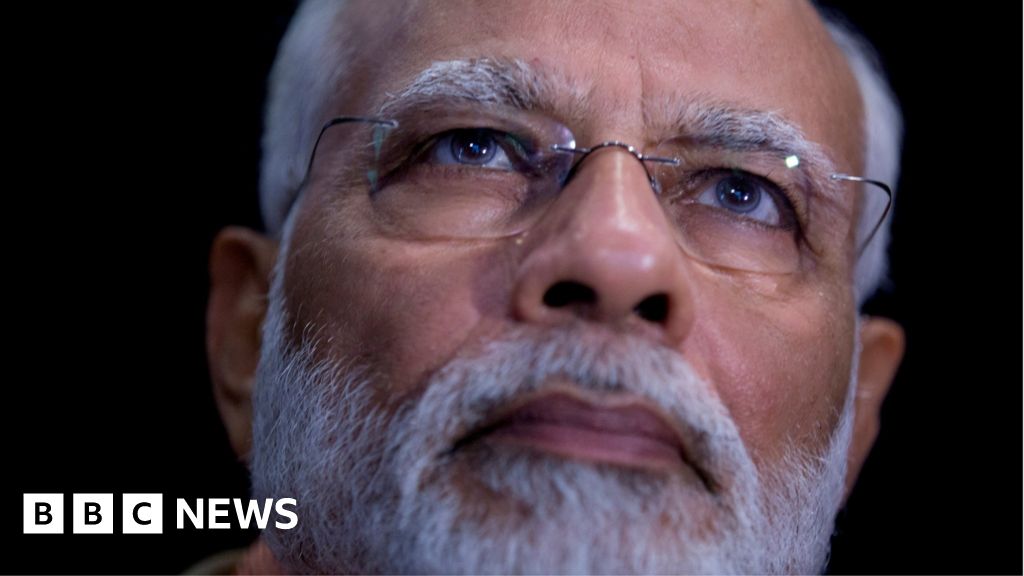

That feeling appears to have surfaced in recent weeks as the BJP’s campaign has pivoted away from the government’s track record and toward sharp rhetoric against Muslims.Modi himself has been accused of using divisive, Islamophobic language, particularly at election rallies, although he denies this, External.

But publicity suggests the BJP may not be as confident as it was a few weeks ago.

Political analyst Niranjan Sirkar said the party may be trying to shore up its supporters in states such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, where Hindu-Muslim polarization has paid off in the past. This is particularly important for motivating young mobilizers, who may also be affected by issues such as unemployment.

The party also seems concerned that there won’t be an overwhelming national issue or wave like the past two elections. In 2014, there was intense public anger against a Congress-led government seen as corrupt; in 2019, after deadly attacks on Indian troops were followed by airstrikes on alleged militant targets on Pakistani soil, national security became a priority the dominant factor in this movement.

“So this may still very much be a vote about how much trust you have in the leader or how much trust you have in the party, but in the absence of a wave, the issues will become more localized,” Serkar said. .

The BJP hopes Modi’s larger-than-life image will push them over the line, but analysts say that could also be a problem.