Dominican Republic President Luis Abinader is set to win re-election on Sunday as voters chastise him for his crackdown on immigrants from neighboring Haiti, his anti-corruption campaign and his management of one of Latin America’s best-performing economies. Management welcomes.

Abinader, a former tourism executive, received 59% of the vote, while his closest rival, three-time former president Leonel Fernández, received 27%; provincial governor Abel Abel Martínez received 11% of the vote, while his vote share was 21.5%. According to the Dominican Republic’s national electoral authority, the votes have been counted.

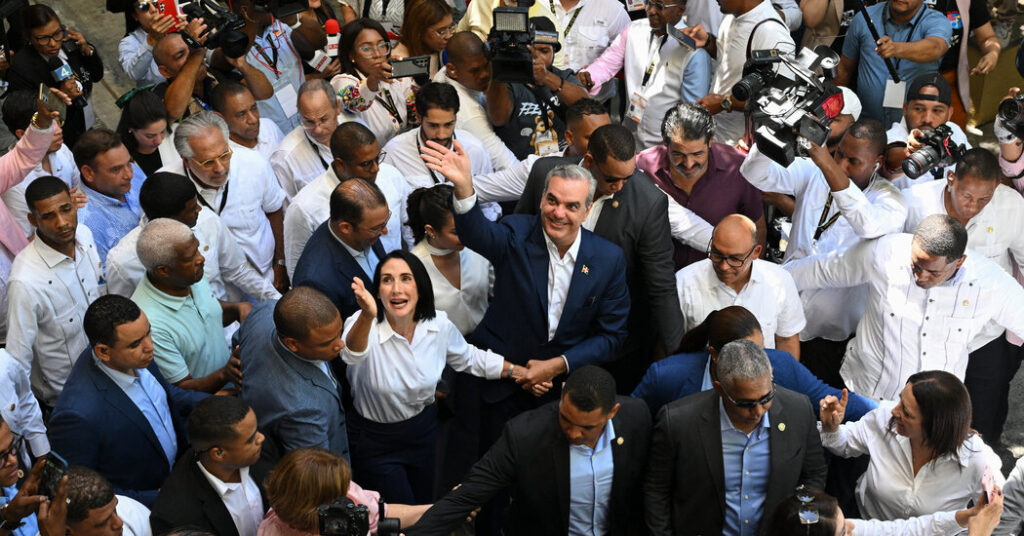

Both Mr. Fernandez and Mr. Martinez called Mr. Abinadel on Sunday evening to acknowledge and congratulate him, although full official results were not yet available and are expected to be released in the coming days. In his victory speech, Abinader thanked his rivals and those who voted for him.

“I accept the trust placed in me,” Mr. Abinader said. “I will not let you down.”

This election shows how political leaders can turn immigration concerns to their advantage.

The Dominican Republic expelled tens of thousands of Haitians this year as they fled gang-fueled lawlessness, despite U.N. calls to stop. Mr. Abinader went a step further by building a border wall between the two countries that share the Caribbean island of Hispaniola.

“He has shown who has the most say on this issue,” said voter Robert Luna, who works in marketing in Santo Domingo, referring to Abinader’s hard-line immigration policies. “He’s fighting for the aspirations of the Founding Fathers.”

A possible first-round victory for Mr. Abinader also shows that what separates the Dominican Republic, one of Latin America’s fastest-growing economies, from the rest of the region is that many of the region’s leaders are not like Abinader. Mr. Derr came to power at the same time.

“This is definitely not a ‘change’ election, like so many other recent elections in Latin America,” said Michael Shift, a senior fellow at the Washington-based research group Inter-American Dialogue.

Much of Mr. Abinader’s support also stems from his anti-corruption measures. He won his first term in 2020, vowing to stamp out long-standing corruption in the political culture of the Dominican Republic, a country of 11.2 million people.

He appointed former Supreme Court justice Miriam Germán as attorney general. She oversaw investigations that ensnared senior officials from the previous administration, including a former attorney general and a former treasury secretary.

The investigation has focused largely on opponents of Abinader, fueling criticism that his own government has survived. But other initiatives, such as the passage of the Asset Forfeiture Act of 2022, raise hope for lasting change. Forfeiture laws are viewed as an important and groundbreaking tool for disrupting and dismantling criminal enterprises and stripping them of their ill-gotten property.

Dominican political analyst Rosario Espinal said Mr. Abinader could have won reelection simply by focusing on the fight against corruption, as he did in 2020, “but it wouldn’t to get the advantage he wants”.

Ms. Espinal said Mr. Abinadel instead supported nativist immigration policies traditionally pushed by the Dominican far right. “He needed to find a new topic that resonated,” she said. “He discovered that in his migration.”

Exploiting anti-Haitian sentiment is nothing new in the Dominican Republic.

Rafael Trujillo, the xenophobic dictator who ruled the country from 1930 to 1961, institutionalized a campaign to portray Haitians as an inferior race and ordered the massacre of thousands of Haitians in 1937 and Dominicans of Haitian descent.

Nearly every other country in the Americas offers birthright citizenship. But a 2010 constitutional amendment and a 2013 court ruling excluded Dominican-born children of undocumented immigrants from citizenship.

In practice, according to rights groups, this means that some 130,000 descendants of Haitian immigrants live in the Dominican Republic without citizenship despite being born in the country.

As Haiti descends into chaos following the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, Abinadel is adding to anti-immigration measures already enshrined in Dominican law.

He suspended visas for Haitians in 2023 and then closed the border with Haiti for nearly a month over a dispute over Haiti’s use of water from a river shared by the two countries to build a canal.

“He has to take a tough stance,” said Sandra Ventura, a 55-year-old businesswoman from Tamayo in the south of the country, of Mr. Abinader’s immigration policies.

Dominican immigration officials went further, with some accused of looting Haitian homes and launching a campaign to detain and deport Haitian women who were pregnant or had recently given birth.

Pablo Mera, academic director of Dominican University’s Pedro Francisco Bono Institute, called Abinadel’s policies toward Haiti a “public and international disgrace,” especially toward pregnant Haitians. treatment.

“What happens is you get votes,” Mr Meira added. “The candidates are competing over who is the most anti-Haitian.”

Before the election, an overwhelming majority of Dominican voters said unrest in Haiti was affecting the way they voted. Mr. Abinadel clearly benefits from such concerns, with nearly 90% of voters expressing support for him building a border wall.

Many Dominican diaspora are also allowed to vote in elections, with more than 600,000 eligible voters living in the United States and more than 100,000 in Spain.

Abinadel has defended his immigration policies, saying they are no different from measures taken by countries such as Jamaica, the Bahamas, the United States and Canada to limit the entry of Haitians fleeing the crisis.

“I have to take all necessary measures to keep our people safe,” Abinader told the BBC in a recent interview. “We are just enforcing our laws.”

Mr. Abinader’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Still, some voters don’t trust the current president. Tirso Lorenzo Piña, a janitor and evangelical Christian in Santo Domingo, said he was unhappy with Abinadel’s support for admitting Palestine as a member at the United Nations.

“Everyone has his own ideology, his own ideas, his own way of thinking,” Mr. Pina said. “But I don’t like him.”

Still, Abinader benefited from divided opposition and broad consensus in the Dominican Republic in favor of investor-friendly policies to spur economic growth. His handling of the pandemic has also been helpful, distributing vaccines relatively quickly and allowing Dominican tourism to rebound while some other countries required visitors to quarantine.

Tourism is the mainstay of the economy, accounting for approximately 16% of gross domestic product. The World Bank predicts that the Dominican Republic’s economy will grow by 5.1% this year.

Although the country’s economy has expanded at three times the Latin American average over the past two decades, persistent inequality has exposed Mr. Abinader to criticism. He responded by expanding a popular cash transfer program targeting the country’s poorest residents.