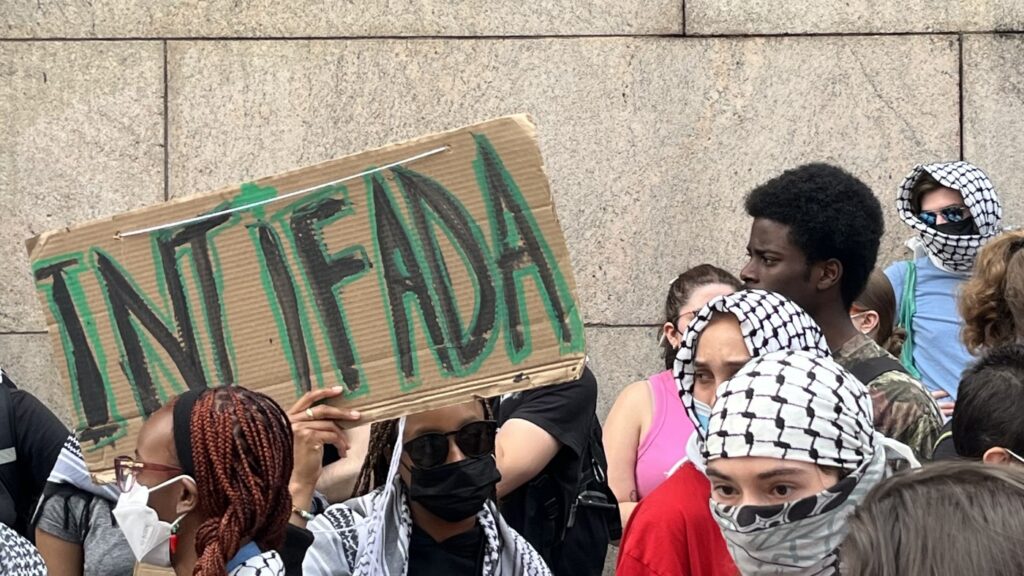

Pro-Palestinian protesters at Columbia University in early May. Slogans calling for an “intifada” have become central to many demonstrations against the war in Gaza and Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories.

Adrian Florido/NPR

hide title

Switch title

Adrian Florido/NPR

NEW YORK — People chanted provocative slogans at a recent pro-Palestinian protest at Columbia University.

“Uprising! Uprising! Long live the uprising!

The term has become one of the bone of contention between people with opposing views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, turning language into a battleground.

Many who protest against Israel’s attack on Gaza say the “intifada” is a peaceful call to resist Israel’s occupation of Gaza and the West Bank. But many Jews heard slogans such as “Globalize the Intifada” calling for violence against them and Israel.

“Intifada” is an Arabic word usually translated as “uprising.” But the word’s role in the painful history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict gives it meaning far beyond that, making it a word that evokes strong emotions on both sides.

The long-running protests and civil unrest against the Israeli occupation in the late 1980s became known as the First Intifada. A second, more violent uprising began in the early 2000s. During the second intifada, Palestinian militant groups adopted bloodier tactics, often carrying out suicide bombings in restaurants and buses, killing about 1,000 Israeli civilians and soldiers. Israel responded with ground troops and tanks, killing more than 3,000 Palestinians.

For Eliana Goldin, the leader of a pro-Israel group at Columbia University, the term “intifada” is inseparable from this violence.

She grew up in a Zionist household and “the word Intifada was associated only with death, terrorism and destruction. So ‘Intifada’ still has a strong feeling to it, like someone saying the Holocaust.” Or if someone mentions any disaster that happened to a people you thought you belonged to.

To her, the slogans sounded like incitement to repeat acts of violence against Jews.

For many, this is a call to liberation

For Basil Rodriguez, the word has nothing to do with violence. A Palestinian-American graduate student at Columbia University, she said that when she chanted “Intifada” at the protests, she expressed her commitment to the people’s struggle against Israel and called for an end to the status quo of the conflict.

“For me, it’s just liberating,” she said. “Free Palestine from the apartheid regime and military occupation. For me, it requires freedom and change.

In early May, a pro-Palestinian march was held near Columbia University.

Adrian Florido/NPR

hide title

Switch title

Adrian Florido/NPR

There are several reasons why people interpret the word differently, said Taoufik Ben-Amor, a linguist and professor of Arabic studies at Columbia University.

Intifada comes from the Arabic root meaning to shake off, like dust from a cloth. Arabic speakers use the term to describe any social uprising aimed at breaking free from an oppressive system, such as the uprising against the Iraqi monarchy in the fifties. But Ben-Amor said it would be easier for non-Arabic speakers to separate the word from its meaning.

“It’s different when someone who knows Arabic uses the word,” he said, “as opposed to someone who doesn’t know Arabic and only knows the word in the context of it being politicized.”

But he also said the decision by U.S. pro-Palestinian protesters to use the Arabic word rather than translate it was a deliberate choice — one that has implications for both sides.

“If you take the word ‘intifada’ and make it uprising,” he says, “then it becomes an English word that people are completely familiar with. By not translating it into English, you can actually define its meaning any way you want. , so the word became a two-handed weapon—one that could be used in ongoing political struggles.

The word and its reception have evolved over time

He said Arabic words are often stigmatized by being associated with violence and terrorism when they do not themselves have connotations of violence and terrorism. In the case of “Intifada,” its meaning has evolved as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has evolved, having different associations with different people.

The pain and trauma experienced by Israelis during the Second Intifada has shaped their perception of the word, which explains why slogans calling for intifada revolution may shock them. But Ben-Amor noted that the second intifada was also very painful for the Palestinians, who suffered three times as many deaths as Israelis. But he said they tend not to shy away from the word because it has broader ties to their desire to escape the occupation and is not necessarily related to violence.

Eliana Goldin, a Jewish undergraduate at Columbia University, said she hopes her classmates chanting “uprising” at protests are not actually promoting violence against Jews. But she said that was hard to believe because on her campus, she also heard chants that she said suggested Israel’s annihilation.

“They chanted ‘We don’t want two states, we want all the states,'” she said. NPR actually heard that slogan at Columbia University. “They chanted ‘Death to the Zionist State.'” Why would I believe that the Intifada did not mean what I thought it meant, when so many other statements in the same slogan were clearly directed toward the destruction of the Jewish people?

She said she wished the protesters had chosen a different word because it strikes fear in the hearts of many Jews, including people like her who, despite being a Zionist, call Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories a A tragedy.

Basil Rodriguez rejects the idea that she should sanitize her language at protests.

“Arabic is our indigenous language as Palestinians,” she said. “I think we have to not say a word because it’s Arabic, and I think that idea feeds into the racist assumption that Arabs are terrorists. So I will never stop saying the word ‘uprising.’

Tawfiq Ben-Amour said the stakes are high when it comes to words like uprising and other controversial words like genocide, martyrdom, resistance and others. The words used to talk about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have always had the power to influence public sentiment, and likely always will.