Addison Guerrero is anxiously preparing for her rite of passage – her driver’s test.

So Sunday began, like so many days lately, with her practicing driving with her mother, Patti Talbot, and her 14-year-old brother, Aiden Guerrero.

The drive, though, took her back to history. She drove her family — on the highway — to visit Los Angeles National Cemetery and the grave of her great-great-grandfather, Roy D. Doron. Born on April 24, 1895, Doron worked as a farrier during World War I, a time when cars were rare and men like him traveled to far-flung places to calm animals with bombs exploding around them.

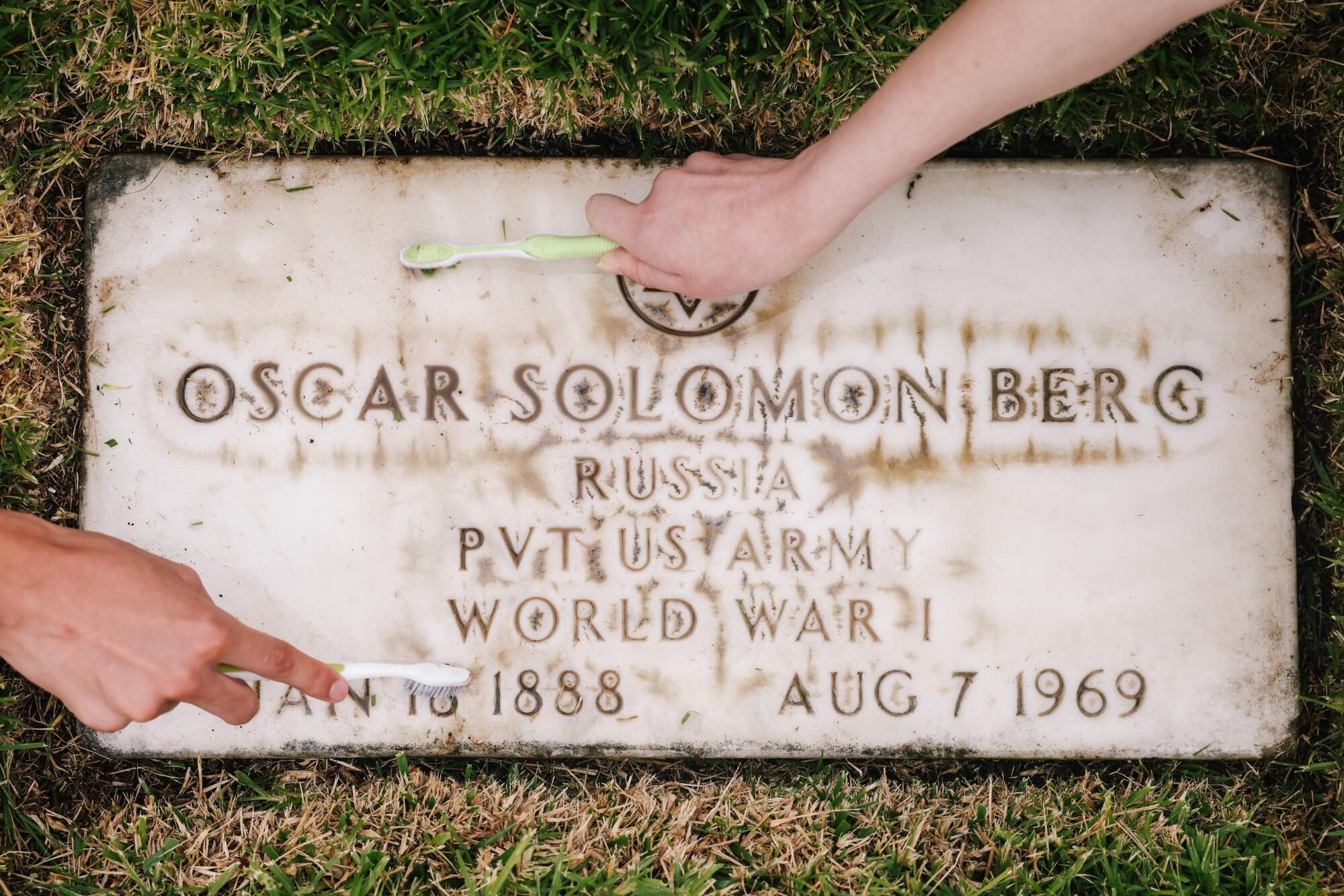

Brother and sister Aiden and Addison Guerrero are cleaning the graves around their ancestors.

(Danya Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

Now, Guerrero is hunched over her brother, scrubbing his tombstone and his “neighbor’s” graves with a toothbrush. Her grandfather and grandmother, Brad and Chris Talbot, both 73, started the tradition about 50 years ago. They knew little about Roy’s wartime service but described him as a quiet man who later traveled with Carnival and was an early employee of Disneyland.

“I can’t imagine how scared those horses were,” Brad said, using garden shears to cut the grass tightly around the marble.

Patty Talbot (from left), Brad Talbot, Addison Guerrero, Chris Talbot and Aiden Guerrero clean up their family member’s “neighborhood” grave.

(Danya Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

His wife, Chris (Roy’s granddaughter), wore a cowboy hat emblazoned with an American flag and watched the game. Brad has been accompanying her to cemeteries since they first started dating in the early 1970s, and she’s “excited to be training the next generation.” The couple owned a Corvette and joined a club where they learned the best way to keep its details clean was to use a toothbrush.

She can’t express exactly why this activity brings her so much satisfaction, other than its connection to her parents, who are also deceased. The family placed three bouquets of flowers purchased at Ralph’s home next to Doron’s grave.

They also placed a bouquet of flowers on the grave next to Doron’s grave. Family members like to say Doron and his neighbors were friends. Maybe they know each other. So they cleared the grass and wiped the covering off the graves. They then found the only farrier found in the cemetery and cleaned his grave.

Army Civil Affairs Capt. Oliver Kay joins his twin sons, Xavier and Max, center left, as they arrange flags on graves and talk about U.S. history at Los Angeles National Cemetery on Sunday.

(Danya Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

Memorial Day weekend includes big band performances and other events at the cemetery. Hundreds of volunteers came to each grave Saturday to place flags and reenact the Rough Riders from the Spanish-American War. Monday’s festivities will include speeches from elected officials and other high-profile guests. But Sunday morning, dark and cold, was filled with quiet moments as loved ones reconnected and strangers pondered the sacrifices so many service members have endured.

Oliver Kay, wearing a military green uniform, knelt next to his twin sons, Max and Xavier. Kay served in the British Army for six years before joining the US Army and, 14 years later, now serves as a Captain in the Civil Service. His sons asked him “which of my dead friends are buried here.”

He told them that they were not buried here but in distant tombs around the world. Visits to the cemetery sparked curiosity in his sons. Surrounded by so many stories, their interest in history will only grow, he said.

Scott Sargent, who works as a security guard at Los Angeles National Cemetery, checks the gravesite of his family member, Lewis L. Owens, on Sunday.

(Danya Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

Security guard Scott Sargent, 59, is in awe of soldiers from places like Syria, China or Ukraine. He was equally impressed by the variety of jobs the deceased performed – whether as a balloonist, driver or mechanic. But the former Cudahy police officer’s greatest satisfaction comes when he encounters someone searching for a loved one or when a flag falls.

He was happy with the little help he was able to offer as he readjusted the fallen flag.

Sometimes he would stop at two inaccessible graves. One is on the south side of the cemetery, near where a large oak tree once stood in the late 1960s.

Louis Owens

pennsylvania

U.S. Army Sgt.

Second World War

September 16, 1920 – August 6, 1968

He remembers visiting his stepfather’s grave as a child.

“There’s a lot of amazing life here,” he said, “including his.”