British Broadcasting Corporation

British Broadcasting Corporation“I don’t deserve to be here” is a protest you’ll hear in prison. But as Tetyana Potapenko wore maroon overalls, she insisted she was not who the Ukrainian government said she was.

A year into her five-year sentence, she was one of 62 convicted collaborators in this prison, held in solitary confinement with other prisoners.

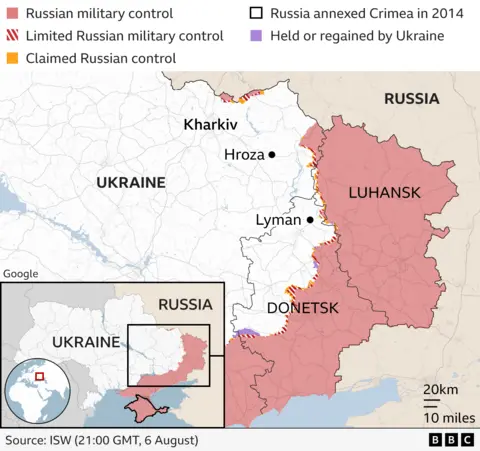

The prison is located near Dnipro, about 300 kilometers (186 miles) from Tetyana’s hometown of Leman. Lyman, close to the Donbas front line, was occupied by Russia for six months and liberated in 2022.

As we sit in the pink room where prisoners can call home, Tetiana explains that she has been a community volunteer for 15 years, liaising with local officials but took on these after the Russians arrived The duty took its toll on her.

Ukrainian prosecutors claim she illegally held an official position with the occupiers, which included distributing relief supplies.

“Winter is over, people have no food, and someone has to advocate,” she said. “I couldn’t leave those old people. I grew up among them.

The 54-year-old is one of nearly 2,000 people convicted of colluding with Russia, and the bill is being drafted almost as fast as Moscow is progressing through 2022.

Kiev knew it had to prevent people from sympathizing with and cooperating with the invaders.

So in little more than a week, lawmakers passed amendments to the criminal code that would criminalize cooperation — something they have been unable to agree on since Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula in 2014.

Before the full-scale invasion, Tetiana liaised with local officials to provide neighbors with supplies such as firewood.

She said that after Russia’s new rulers took office, a friend convinced her to contact them too to secure much-needed medicine.

“I’m not cooperating with them voluntarily,” she said. “I explained that people with disabilities could not get the medications they needed. Someone filmed me and posted it online, and Ukrainian prosecutors used it to claim I worked for them.

After Lehmann was released, the court was presented with documents she signed indicating that she had taken an official position with the occupation authorities.

She suddenly became animated.

“What’s my crime? Fighting for my people?” she asked. “I never worked for the Russians. I survived and now I’m in prison.”

Onysiya Syniuk, a legal expert at the Zmina Center for Human Rights in Kyiv, explained that the 2022 cooperation law was enacted to prevent people from helping advancing Russian troops.

“However, the legislation covers a variety of activities, including those that do not harm national security,” she said.

Collusion crimes range from simply denying the illegality of the Russian invasion, or supporting the Russian invasion in person or online, to playing a political or military role for the occupying power.

The penalties that come with it are severe, up to 15 years in prison.

Of nearly 9,000 collaborative cases to date, Ms Syniuk and her team have analyzed most of the convictions, including Tetyana’s, and said they were concerned the legislation was too broad.

“Now, people who provide vital services in the occupied territories will also be held accountable under this legislation,” Ms Sinyuk said.

She thinks lawmakers should consider the reality of living and working under occupation for more than two years.

We drove to Tetiana’s hometown to visit her frail husband and disabled son. As we approached Lehmann, the scars of the war were clearly visible.

Civilian life dries up and vehicles gradually turn military green. Sagging power lines hang from collapsed towers and the main railway line has been swallowed up by overgrown weeds.

While the sunflower fields were unscathed, the same could not be said for the town. It was hit hard by air raids and fighting.

The Russians have now fallen back to within nearly 10 kilometers (6 miles). We were told that they usually start shelling around 15:30 and the day we visited was no exception.

Tatiana’s 73-year-old husband, Volodymyr Andreyev, told me that he was “in trouble” — without his wife, the family was falling apart, and he and his son had to rely on help from neighbors. keep the wolf from the door.

“If I’m weak, I burst into tears,” he said.

He had a hard time understanding why his wife wasn’t with him.

Tetiana could have been given a shorter sentence if she had pleaded guilty, but she declined. “I will never admit that I am an enemy of the state,” she said.

But there were also enemies of the state—whose actions had fatal consequences.

last fall, We walked on the blood-stained land of Hroza village after liberation Located in the Kharkiv region of eastern Ukraine. A Russian missile hit a cafe where a funeral for a Ukrainian soldier was being held – a funeral that would have been impossible for Hroza during the Russian occupation.

Fifty-nine people—almost a quarter of the population of Hroza—were killed. We knocked on the door and found the children home alone. Their parents didn’t come back.

Security services later revealed that two local men, Vladimir and Dmytro Mamon, tipped off the Russians.

The brothers were former police officers who allegedly began working for the occupying forces.

After the village was liberated, they fled across the border with the Russian army, but kept in touch with their old neighbors – they inadvertently told them about the upcoming funeral.

Yakiv Lyashenko/EPA-EFE/REX

Yakiv Lyashenko/EPA-EFE/REXThe brothers have since been charged with treason but are unlikely to be jailed in Ukraine.

This is roughly the story of Kiev’s struggle with collaborators. Those who committed more serious crimes – directing attacks, leaking military information or organizing fake referendums to legitimize occupying forces – were mostly tried in absentia.

Those facing lesser charges often end up in the dock.

Under the Geneva Conventions, Russian occupying forces must allow people to continue living and provide them with the means.

As Tetyana Potapenko tells it, she tried to do this when the troops entered Ryman in May 2022.

Her case is one of several we have uncovered in eastern Ukraine.

They include a principal jailed for accepting Russian lessons – his lawyer said his defense was that although he accepted Russian material, he did not use it. In the Kharkiv region, we heard that a sports venue manager faced 12 years in prison for continuing to hold games during the occupation. His lawyer said he had organized only two friendly matches between local teams.

In the view of the United Nations, these cooperative convictions violate international humanitarian law. The report stated that from the outbreak of the war in February 2022 to the end of 2023, one-third of the weapons handed down in Ukraine lacked legal basis.

“Crimes have been committed in the occupied territories and people need to be held accountable for the harm they have caused to Ukraine, but we have also seen the law being applied unfairly,” said Danielle Bell, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. The country’s rights monitoring mission.

Ms Bell argued the law did not take into account someone’s motives, such as whether they were actively cooperating, or trying to earn an income, which the law allowed them to do. She said based on its vague wording, everyone was convicted.

“There are countless examples of people acting under duress and performing their duties in order to survive,” she said.

That’s exactly what happened to Dmytro Herasymenko from Tetyana’s hometown of Lehmann.

In October 2022, he emerged from his basement after the artillery and mortar fire subsided. this The front line has passed through Lehmannand it was under Russian occupation.

“People had been without electricity for two months,” he recalled. Dmytro has been an electrician in the town for 10 years.

Occupation authorities asked volunteers to help restore power, and he raised his hand. “People have to survive,” he said. “[The Russians] Said I could work like this or not work at all. I was afraid of rejecting them and being hunted by them.

For Dmytro and Tetyana, the relief of liberation was short-lived. Officials from the country’s security service (SBU) took them in for questioning after Ukraine regained control of the town.

After pleading guilty to supplying electricity to the Russian occupiers, Dmytro was quickly given a suspended sentence and banned from working as a state electrician for 12 years.

We found him in the garage, where he now works as a mechanic. The shiny tools reflect his forced career change. “I cannot be judged in the same way as my collaborators who helped guide the missile,” he said.

His protests echoed those of Tetiana. “How do you feel when foreign troops come in?” she asked. “Of course I’m afraid.”

This fear is justified. The United Nations has found evidence that Russian forces are targeting and even torturing people who support Ukraine.

“We have encountered cases where people have been detained, tortured and disappeared simply for expressing pro-Ukrainian views,” said the UN’s Ms Bell.

From the moment Moscow invaded Crimea in 2014, the definition of “pro-Russian” in the eyes of Ukrainian lawmakers changed – from simply supporting closer ties to supporting a Russian invasion that was seen as genocidal.

That same year, Russian puppet armies funded by the Kremlin also captured a third of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Often it is older people who choose or are forced to live in a career. Some may be too frail to leave.

Still others are nostalgic for the Soviet Union or sympathetic to modern Russia.

But given that Ukraine may one day have to reunify, will cooperation laws be too harsh?

One congressman who helped draft the bill had a blunt message: “You’re either with us or you’re against us.”

Andriy Osadchuk is deputy director of the parliamentary law enforcement committee. He strongly objected that the legislation breached the Geneva Conventions but acknowledged that it needed improvement.

“The consequences are extremely serious, but this is no ordinary crime. We are talking about life and death,” he said defiantly.

Mr. Osadchuk argued that international law must, in fact, catch up with the war in Ukraine, not the other way around.

“We need to build Ukraine on liberated territory, not to please people from the outside,” he said.

The United Nations monitoring mission acknowledged that some progress had been made. The Prosecutor General of Ukraine recently instructed his office to comply with international humanitarian law when investigating cases of cooperation.

Ukraine’s parliament also plans to introduce more amendments to the legislation in September. One proposed change is that some would be fined rather than jailed.

Currently, Kyiv considers countries like Tetyana and Dmytro to be acceptable recipients of harsh justice if it means Ukraine can finally escape Russian control.

The pair claimed they simply regretted not escaping when the Russians first invaded.

But with the state under surveillance and Lehmann at risk of another downfall, it’s unclear how candid they can be.

Additional reporting by Hanna Chornous, Aamir Peerzada and Hanna Tsyba.

All BBC images by Lee Durant.