Thirty years ago, sociologist Craig Reinarman observed that there is something “woven into the very fabric of American culture” that makes it easy for us to believe that “chemical demons” are responsible for “social ills.” . He added that every moral panic about drugs since the 19th century had been fueled by “media amplification,” in which the dangers of specific substances were exaggerated and distorted.

Now that recreational marijuana is legal in about half the U.S. states and more Americans are smoking it than ever before, the chemical bogeyman is back, and he’s back with a new paper in the New York Times. Journal of the American Heart Association Developed by researchers at Harvard University and the University of California, San Francisco.

This research is in New York Times and Washington post, made so many egregious statistical errors that it became the poster child for junk science. This paper would be ridiculous if it didn’t provide terrible medical advice. Researchers are doing almost everything wrong.

This is not to say that the author is guilty of fraud or misconduct. In fact, they do exactly what Dr. Doctor does. Students are taught what to do, what journal editors look for, reviewers approve, universities reward, and funding agencies fund. Because this paper reaches the wrong conclusion using traditional methods, it illustrates a deep crisis in academic research.

We forget that the purpose of scientific research is not to seek institutional approval. This is the pursuit of truth.

The study setup was very simple. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducts an annual telephone survey asking people about their health and behavior. The authors studied the incidence of cardiovascular problems among three types of marijuana users and those who did not use it.

This is an observational study, not a controlled experiment, which means you can’t infer cause and effect. Most researchers are transparent about the limitations of their data.

Not in this case. The authors even drew “clinical implications” from their findings, writing that patients should be “advised to avoid marijuana use to reduce the risk of premature cardiovascular disease and cardiac events.” The media took them at their word.

This is quackery. Observational studies simply cannot show that quitting marijuana reduces cardiovascular problems.

Observational studies can only show correlation, not causation. In this case, we can determine that there is no causal relationship because the telephone survey measured cannabis use that occurred after the onset of the disease. It asked participants about marijuana use in the past 30 days and cardiovascular problems at any time in the past.

How could a bong from a week ago, or a THC gummy from last Saturday, cause a stroke in someone 10 years ago?

Another problem is that the data don’t show people with cardiovascular problems; they show people who have survived cardiovascular disease. Marijuana was hypothesized to reduce cardiovascular mortality.

We expect this study will show more cannabis users suffering from heart disease and stroke because they will live to report their cardiovascular problems in telephone surveys. More non-users with cardiovascular problems may have died and were unable to respond.

This is the same reason that people who wear motorcycle helmets are more likely to be hospitalized due to accidents, as three times as many people die before reaching the hospital without helmets.

Although the data came from a telephone survey, the authors did not take into account the unreliability of what people might tell strangers over the phone about their health and drug use.

The researchers even had the audacity to assert that such surveys tend to be accurate, while citing only two studies to back up the claim—a 1982 paper that found such data to be “highly unreliable” and nearly impossible to interpret and explain. A 2004 study showed that about half of self-reported cardiovascular problems were fictitious.

To make matters worse, the fictitious self-reports are not random but occur at much higher rates in some groups than in others, which would skew any findings.

Researchers must also address other behaviors associated with marijuana use that are known to affect cardiovascular health. Marijuana users were more likely to be current and former smokers, more likely to be male, and they drank more alcohol, all of which have been linked to cardiovascular problems.

In fact, the cannabis users in the study had fewer of all three types of cardiovascular problems measured in the study—an inconvenient point the authors only mention in a jargon post later in the paper.

For example, people who don’t smoke marijuana are more likely to develop coronary heart disease than people who do or don’t smoke marijuana every day.

This does not necessarily negate the author’s argument. To dig deeper into the data, they should try to find a meaningful subgroup — such as overweight, middle-aged men — in which marijuana users have more cardiovascular problems. They can then ask whether marijuana or other factors explain the difference.

So how do researchers claim to support their thesis? They torture the data until they make false confessions.

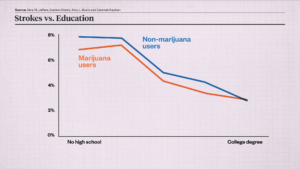

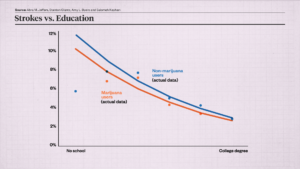

The main tool they use is logistic regression. The authors examined the association of marijuana use with stroke and educational attainment.

This is the stroke rate based on time spent in school with and without marijuana use.

As you can see, more education is associated with fewer strokes. But for every educational level, marijuana users were less likely to have a stroke than non-marijuana users until college, when the two lines intersected.

According to this chart, marijuana appears to reduce strokes. But correlation doesn’t prove causation.

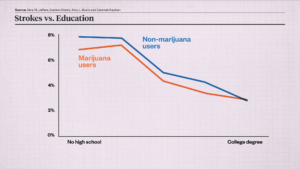

However, the study authors hoped to use these numbers to support an opposite conclusion. First, they replaced the actual data with logistic regression. This resulted in this chart.

But the data still refuses to admit it. Marijuana users still appear to be healthier. So the authors move on. They replaced the regression line with a 95% confidence interval, which shows the chance of a population parameter falling between a set of values. Now there seems to be some doubt as to whether cannabis is beneficial or harmful, as blue is lower than orange in some places.

It is inappropriate to use confidence intervals.

Confidence intervals are useful when we are unsure about the data, but we know exactly what the data is in this case. The uncertainty is not in the raw numbers; It was introduced by researchers when performing logistic regression on the data.

The authors went on to add more variables to the logistic regression, including age, sex, race, alcohol use, smoking history, body mass index, physical activity, and diabetes. In all cases, logistic regression masks the actual data. It adds no information. If across all subgroups marijuana smokers have fewer cardiovascular problems than non-marijuana smokers, you don’t need logistic regression or anything else to disprove that marijuana use is the cause of cardiovascular problems.

Logistic regression still failed to show a statistically significant increase in cardiovascular risk among cannabis users. Therefore, the authors next excluded inconvenient data.

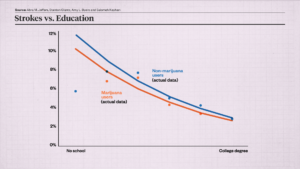

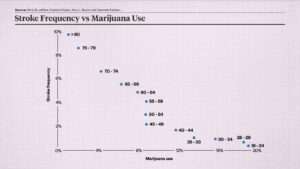

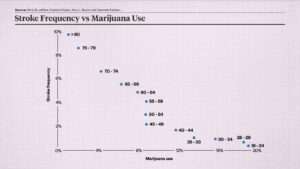

When they tested age as a proxy for stroke frequency and marijuana, they came up with the following results.

Note that stroke frequency decreases as marijuana use increases, for obvious reasons: Older adults use less marijuana and have more strokes. This does not prove that cannabis benefits cardiovascular health. But it does show that marijuana is not the primary cause of cardiovascular problems, which occur mostly in age groups where marijuana use is rare, and that most marijuana use occurs in age groups where cardiovascular problems are rare.

The two dots in the upper left corner represent people over 74, who have a high rate of strokes and a low rate of marijuana use. This population helped weaken the authors’ conclusion that marijuana causes cardiovascular problems. Therefore, the authors excluded these two data points from the study, although they are just as meaningful as any other data.

How do the authors explain the decision to discard relevant data? They claimed that these groups, which have the highest rates of cardiovascular problems, did not use enough cannabis to qualify for the study.

It’s like trying to prove that college calculus leads to alcoholism but excluding frat boys because few of them are math majors. terrible. But ignoring contrary data does ultimately get the confession researchers want.

I can keep going. For example, the authors did not report the accuracy of their confidence intervals; they excluded all survey data from 1988 to 2015 and after 2020, but did not explain why; they were unable to distinguish between food and smoking; and they did not preregister their hypotheses or use hold back the sample, which makes it impossible to assess whether their findings are statistically significant; etc.

So, what does this mean? Reputable journals publish blatant nonsense; peer review does not filter out significant errors; guerrillas and journalists cite papers that fit their preferred narrative without reading, understanding them or caring about their validity; researchers being criticized for Potemkin was rewarded for his research rather than his pursuit of truth.

The biggest scandal in academia is not outright fraud but these traditional methods.

We are haunted by chemical monsters and the moral panics they cause.

The only way to stop him is critical analysis. Statistics should be a way to challenge conventional wisdom and combat irrational fears.

The weapons of science have been turned on us.

Photo credit: imageBROKER/Jochen Eckel/Newscom

Musical works: Enids Theme by Night Rider 87, Exalted by Night Rider 87, Shadows in Motion by The Magnetic Buzz, Bionic by Gruber, Get Lost in You by Ben Fox

Video Source: “Years of Anti-Cannabis TV Ads” from The New Yorker

- Video editor: Adani Samat

- Dynamic graphics: Reagan Taylor

- Audio production: Ian Keyser