Efforts to legalize MDMA as a psychotherapy catalyst hit a daunting roadblock on Tuesday when a panel of experts voted overwhelmingly to recommend that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reject Lykos Therapeutics’ new drug application submitted in February. Expert panelists expressed several concerns about two Phase 3 studies on the safety and effectiveness of MDMA in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including lack of blinding of participants, possible underreporting of adverse events, and alleged underreporting of adverse events. The abuse potential of MDMA has been inadequately assessed.

Chief executive Amy Emerson said: “Given the urgent unmet needs of PTSD, we are disappointed with today’s vote and applaud the committee for the challenging and atypical task of evaluating combination drug treatments. “We remain committed to working with the FDA to resolve outstanding issues so that we can find a path forward to ensure that, if approved, MDMA-assisted therapies are introduced responsibly and cautiously into health care.” system. “

Nine of the 11 advisory committee members concluded that MDMA’s effectiveness has not been proven, while 10 members agreed that its benefits did not outweigh its risks. “There seem to be a lot of problems with these data,” said panelist Melissa Decker Barone, a Department of Veterans Affairs psychologist. “Each one might be fine on its own, but when you stack them together … I have a lot of questions about the therapeutic effect.”

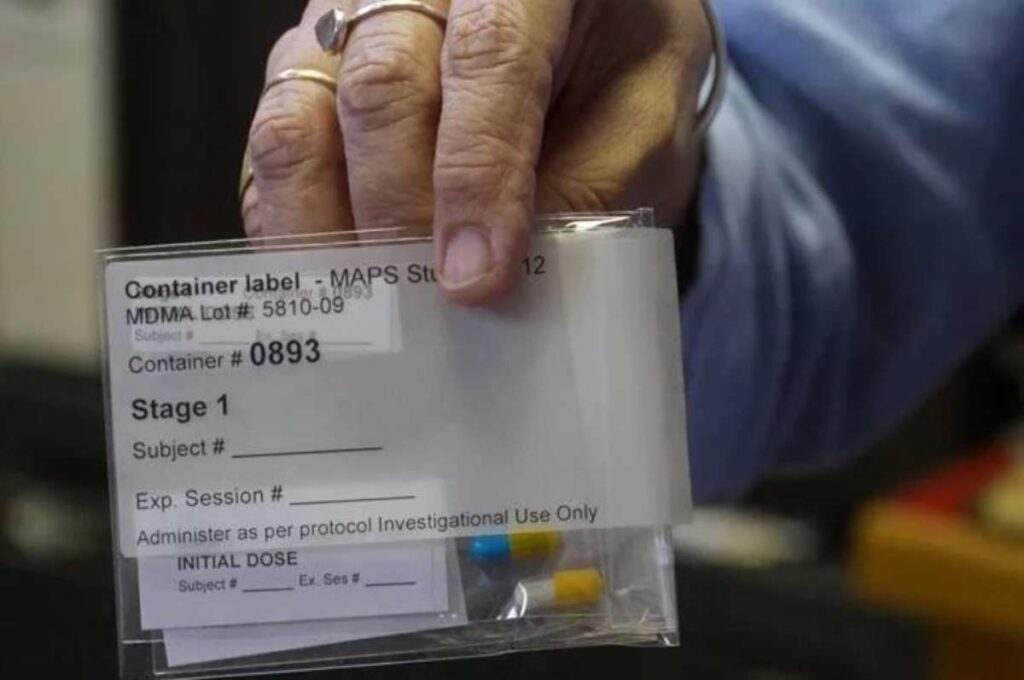

The two clinical trials compared subjects who received MDMA combined with psychotherapy with those who received the same treatment but a placebo. On the face of it, the results of these studies are impressive.

The first study was published in natural medicine In 2021, it involved 90 subjects with “severe PTSD,” as measured by the DSM-5 Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5). The questionnaire is designed to assess issues such as “intrusive painful memories,” hypervigilance, exaggerated startle reactions, insomnia, difficulty concentrating, avoidance of cues reminiscent of the traumatic event, and “feelings of separation or alienation from others.” A second study reported two years later in the same journal involved 104 subjects with “moderate to severe post-traumatic stress disorder.” Both studies found that subjects treated with MDMA had greater decreases in CAPS-5 scores than controls.

The difference is huge. In the 2021 study, CAPS-5 scores (which range from 0 to 80) dropped by an average of more than 24 points in the MDMA group, compared with about 14 points in the placebo group. At the end of the study, two-thirds of the MDMA group “no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD,” while one-third of the control group “no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD.” In the 2023 study, the average score drops were around 24 points and 15 points, respectively. More than 70% of the MDMA group no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis, compared with 48% of the control group.

One of the reasons FDA advisers discounted these results is that the subjects were randomly assigned to two groups and theoretically did not know whether they were taking MDMA, and they might have guessed which group they were in based on whether the expected effects of the drug were present. . The researchers described the placebo as “inactive,” meaning it didn’t even have the stimulating effects of MDMA, so it wouldn’t be difficult for subjects to figure out what they were getting. “While we do have two positive studies,” said FDA clinical reviewer David Millis, “these results are presented in the context of significant functional unblinding.”

A May 2024 report from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) asked the same question. “Due to the effects of MDMA, these trials were largely unblinded,” it said. “Nearly all patients who received MDMA correctly identified themselves as belonging to the MDMA trial group. This always raises concerns about bias, but when we start from These concerns were particularly heightened when multiple experts were there to hear that those involved in the trial (as researchers, therapists, and patients) had very strong prior beliefs about the benefits of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.

The lack of functional blinding is certainly a problem for any study that attempts to rigorously measure the benefit of a drug, especially when the outcome measured is a psychological outcome. For example, critics of SSRI antidepressant drugs such as Prozac argue that clinical studies exaggerate their benefits because they do not take into account that subjects infer from the drug’s side effects that they are getting the real drug, an enhanced placebo effect. possibility.

This problem is difficult to overcome when a drug has significant psychotropic effects, such as ecstasy. Part of the solution is to use active placebos that mimic some of the physiological effects of the drug. For example, psilocybin researchers gave control subjects niacin or low doses of psilocybin itself. But this approach doesn’t completely prevent unblinding, because the same psychoactive effects the researchers were studying were an obvious clue to subjects in the treatment group.

In the case of MDMA, it’s hard to imagine how a true, completely blind study could be conducted, given the unique effects users have long reported. Psychonautical chemist Alexander Shulgin has revealed the previously unappreciated qualities of this compound, saying that it “allowed me to see without reservation, both outside and inside myself.” His account sparked interest in MDMA’s psychotherapeutic potential that predated the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) “emergency” ban in 1985.

Therapists and clients report dramatic breakthroughs with MDMA, which they say makes it possible to overcome psychological barriers and confront traumatic memories without overwhelming fear. Recreational uses that alarmed the Drug Enforcement Administration also highlight the drug’s unique effects, including friendship and emotional openness. As far as the FDA is concerned, this anecdotal evidence doesn’t matter. But without it, there would be no interest in systematic research. At the same time, the subjective effects of MDMA’s fame pose inevitable challenges for researchers trying to meet FDA requirements.

Unblinding isn’t the only concern expressed by FDA advisers. They are also concerned that the negative effects of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy may be underreported.

In the 2021 study, researchers noted that some “treatment-emergent adverse events” were more common in the MDMA group. But they said the effects were “usually transient” and “mild to moderate in severity”. These include “muscle tension, decreased appetite, nausea, hyperhidrosis” [excessive sweating] and feeling cold.

The 2023 study showed similar results. Psychiatric adverse events, the most common of which were suicidal ideation, insomnia and anxiety, “occurred with similar frequency in both groups,” the authors said. However, ICER said a meta-analysis of the two studies “found very low-quality evidence showing no increase in suicidal ideation”.

According to the 2023 study, there were no reported incidents of “MDMA abuse, misuse, physical dependence, or diversion.” Millis apparently thought this was suspicious. “We noticed a distinct lack of abuse-related adverse events,” he said. While this may be due to under-reporting, it may also be due to a lack of such incidents.

“Some are concerned that therapists will encourage patients to make positive reports and discourage patients from making negative reports, including preventing reports of significant harm, which could bias the recording of benefits and harms,” ICER said, adding that It “cannot assess the frequency of falsely reported benefits and/or harms and thereby assess the overall balance of net benefits.”

To give you an idea of what the FDA might consider a concerning MDMA effect, NPR reports, “Another potential sticking point is the lack of data on how patients experience the drug’s acute effects, including ‘euphoria’ or ‘elevated mood’ ‘Wait for the feeling.

In other words, if MDMA can help people overcome serious psychological problems that have plagued them for years, that counts as a benefit. But if it also makes them feel good, that’s problematic and potentially harmful.

More understandably, panel members were alarmed by the “sexual misconduct” of two therapists (a married couple) involved in the MDMA study. MAPS investigated the complaints, which involved inappropriate physical contact during therapy and sexual relations between therapists and subjects that occurred after the study, and confirmed ethical violations. As a result, the therapist “is prohibited from participating in all MAPS-related activities and from being a provider of MAPS-affiliated MDMA-assisted therapy if the treatment is approved.”

This incident, while obviously disturbing, does not fundamentally affect the validity of ecstasy research. The most serious issue on this score appears to be the lack of effective blinding, which is a thorny issue “due to the effects of MDMA,” as ICER notes. It would be paradoxical to allow MDMA’s interesting and potentially beneficial effects themselves to become an insurmountable obstacle to FDA approval.

Although the FDA does not have to follow the advisory panel’s recommendations, it often does. It’s unclear the years-long effort to gain regulatory approval for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. I reached out to Rick Doblin, founder and former executive director of MAPS, for comment on the criticism raised by the panelists, and will update this article if I hear back.

Back in 2018, the FDA designated MDMA a “breakthrough therapy,” meaning it “may demonstrate substantial improvement over existing therapies on one or more clinically meaningful endpoints.” This designation is intended to facilitate the approval of MDMA as a prescription drug. The same goes for the FDA’s decision to grant “priority review” to Lykos’ application.

The rationale for these decisions remains compelling: MDMA seems to help many people who have tried other options without success, often in such dramatic ways that its benefits seem obvious. “Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can cause debilitating symptoms that can severely impact nearly every area of a person’s life,” Harvard psychiatrist Jerry Rosenbaum noted in a Lykos press release. “While We have treatments available, but unfortunately, many people don’t respond or stop treatment early… Research suggests MDMA’s unique properties may work by helping reduce fear in the brain and enhance psychotherapy (the current standard of care) to act as a catalyst.[ing] A window of tolerance for painful emotions and memories, allowing people to access and process painful memories without being overwhelmed.

Verifying these benefits to the FDA’s satisfaction appears to be proving more difficult than MAPS anticipated. Back in 2017, Doblin, who has been defending MDMA’s psychotherapeutic uses for decades, hoped to win FDA approval by 2021. Always an uncertain prospect. Although unlikely to succeed so far, this approach implicitly recognizes the government’s right to decide who can use which psychoactive substances, when and why. Unlocking MDMA’s full potential may require an entirely different understanding of the state’s role in brain regulation.