go through Pennydale, reporter

Mario DiBari

Mario DiBariGabriella Ghermandi laughs as she recalls her annoyance with the so-called Ethiopian Spice Girls, the charity-backed pop group Yegna who hope to change narratives and empower girls through music and women’s empowerment.

All-female group sparking controversy in the UK Because it is partly funded by British aid, some say it is a waste of taxpayers’ money. But for Germandi, the assumption that Ethiopian women must be taught by outsiders is the problem.

“I was like, what?” Germandy told the BBC. “They want to teach us how to empower women? Ethiopia? And all the epics about women?

Therefore, the Ethiopian-Italian writer, singer, producer and ethnomusicologist Gail Mandy also uses music as a way to “show to the world that we have a long history of courageous women who are just as strong as men”.

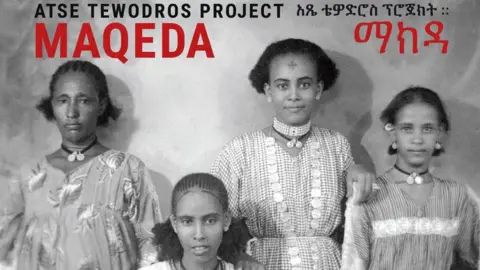

The result is a nine-track album titled Maqeda, the Amharic name for the Queen of Sheba, a very important figure in Ethiopian history.

Each song is a tribute to female figures, communities, rituals and musical styles.

Many would label the album Ethiopian jazz, but it is much more than that, Gaimandi said.

“It’s a deeply rooted Ethiopian music, but at the same time there’s a very avant-garde sound, a very rock and punk sound. You can find everything.”

Maqeda was crafted over four years and brings together Ethiopian and Italian musicians who have collaborated since 2010 as the Atse Tewodros Project, as well as Senegalese guest musicians, as well as a rhythm boxer and a physical music performer.

“We wanted to digest this music,” Gaimandi said of the collaboration, adding that each musician played a role in the arrangement, “because I really wanted my two countries to be one. one”.

Gabriella Gelmandi

Gabriella GelmandiGermani was born in Addis Ababa in 1965 to an Italian father and an Ethiopian-Italian mother.

“Every place, every corner [filled] With music and dancing. I think I’ve learned a rhythm that stays in my blood,” she said.

There was a record shop on the same street as her mother’s clothing store, run by a Greek woman, that played a range of music from Congolese to the Beatles.

where does it feel Performing in nightclubs with other African greats, Germandi would perform with her brothers and on Sundays there would be tea dances at an Italian expatriate club.

Although Germandi had no formal musical training, his thorough immersion in Ethiopian musical styles came from many weddings and church ceremonies in his family life.

Journeys were another constant in Germandy’s childhood – thanks to her father.

In 1935, he left Italy to work in Eritrea, which was then an Italian colony. In 1955, he moved to Ethiopia and met his mother, who was 17 years her junior.

He worked in construction, often traveling to remote areas, and Galmandi often visited.

She was only three months old when she was brought to Ethiopia’s southern Rift Valley. Her father wanted the local Oida people to give her a moytse (“sound name”).

For girls, the blowing of a bull’s horn – any sound heard by an old and young woman waiting together under a tree in the forest became a sound name. The moytse of Ghermandi is tumlele, tumlele, tumlelela.

Gabriella Gelmandi

Gabriella GelmandiHer father died in 1978. Italy. Germandi now lives between Italy and Ethiopia.

But those cherished early experiences have stayed with her, and this latest album draws on childhood visits to remote Ethiopian communities and meticulous research as an adult.

Germandi said she started with the community she grew up with – the Dolzi people from Ethiopia’s southern highlands, whose women lead villages and sing in powerful polyphonic choirs.

You can hear this style of singing in the song “Boncho,” which has up to six voices or voices, each with an independent but harmonious melody. Boncho means “respect” in the Gamo language. .

Gabriella Gelmandi

Gabriella GelmandiGhermandi collaborated with an Ethiopian female poet to write “Set Nat” (She’s a Woman) to counter the Ethiopian saying that a woman achieves something because she is as brave as a man.

“I hate this sentence because it once told me that being a woman is not enough,” Gormandy said, her voice full of passion. “I want to say to the world that being a woman is enough!”

The song is led by the choir, whose call and response has a unique rhythmic feel in the 7/4 time signature. “It’s a very typical place in Ethiopia – it’s a memory from my childhood,” she explains.

Another song, “Kotilidda,” pays homage to the matriarchal society of the Kunama people who live near the border between Eritrea and Sudan. It showcases the avangala, a two-string instrument that sounds like a bass guitar and can only be played by the Kunama people.

“I really wanted to combine traditional Ethiopian instruments with modern instruments because Ethiopia doesn’t promote its traditional instruments enough abroad,” Gelmandi said.

Galileo MC

Galileo MC“I also wanted to show Ethiopian artists that these instruments can be in dialogue with modern instruments and at the same time very modern, even though they are traditional.”

Saba, meanwhile, sang the legendary story of the Queen of Sheba who rode on a camel to Jerusalem to meet King Solomon.

The masinqo – a single-stringed violin – plays an ancient Hebrew melody at the end, honoring Ethiopia’s Jewish community as descendants of those who followed the Sons of Sheba back from what is now Israel.

Gormandi points to similarities between this ancient, possibly mythical journey and the real-life journeys taken by thousands of Ethiopians today fleeing conflict, oppression, drought and poverty in search of a new life elsewhere. .

“The song has the idea of walking and facing all the things you discover on your journey.”

Penny Dale is a freelance journalist, podcaster and documentary maker based in London

Maqeda by Atse Tewodros Project released via Galileo MC

You might be right too.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC