Sverdlovsk Museum of Local History

Sverdlovsk Museum of Local HistoryWhile the United States and Russia were busy finalizing the largest prisoner exchange since the Cold War, a talented but little-known Russian pianist died quietly in prison.

Pavel Koushnir, who has repeatedly protested against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, went on a hunger strike shortly after his arrest in May and later refused to drink water.

He died slowly and without publicity on July 28 – four days after a group of high-profile dissidents were replaced by Kremlin spies, undercover agents and hit men imprisoned in the West.

After the 39-year-old died alone in a pretrial detention center in Birobidzhan, Russia’s far east region, only 11 people mourned at the crematorium.

Siberian independent politician Svetlana Kaverzina said no one tried to convince him not to sacrifice himself because they had no idea what was happening.

“We can’t afford to send him a lawyer – we don’t know,” she wrote on the Telegram messaging app. “He was alone.”

“Foreign Agent Mulder”

At the time of Kushnir’s arrest, his YouTube channel, where he had released four anti-war videos, had only five subscribers.

His “Foreign Agent Mulder” post was a reference to the character from The X-Files, an American TV series popular in Russia in the 1990s, and a reference to a Russian law that allows people deemed politically suspect to be Declared a “foreign agent.” In one clip, Kushnir even appears wearing a hand-drawn FBI badge.

His last film, released in January, recounted the 2022 massacre of civilians by Russian troops in Bucha, a suburb of Kiev.

Months later, Operational Reports, a Telegram channel with close ties to the Secret Service, posted a video showing masked men leading Kushnir into a white minivan.

It added that a criminal case had been opened against him for making public calls to commit terrorist activities, which carries a penalty of up to seven years in prison.

Until August 2, an article published by the online news agency Vot Tak by human rights activist Olga Romanova and pianist friend Olga Shkrygunova revealed the news of his death.

His 79-year-old mother, Irina Levina, later confirmed her son had died.

anonymous

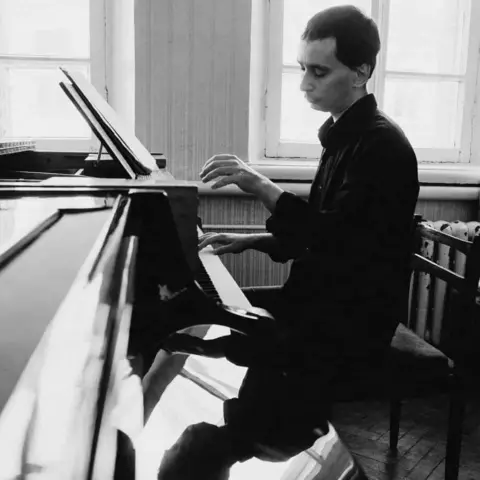

anonymousKushnir was born in Tambov, central Russia. His father, Mikhail, was a pianist and educator, and his mother was a music school teacher.

He began playing the piano at the age of two, and at the age of 17 he gave a stunning two-and-a-half-hour concert, playing 24 preludes and fugues by the composer Dmitri Shostakovich .

Later that year, he was admitted to the Moscow Conservatory, where he cultivated a “dissident image,” according to classmate Julia Wertman, often wearing shabby coats and black clothes with pockets Carrying a half-liter bottle of vodka.

In a 2005 interview, when asked what piece he would never perform, he replied: “The Russian national anthem.”

Shkrygunova said that after graduation, Kushnir deliberately went to work in a small city, believing that he would have more musical and personal freedom outside of Moscow.

He moved to Yekaterinburg and then Kursk and spent three years in Kurgan, a city east of the Ural Mountains, before losing his job with the philharmonic orchestra there in 2022.

Shkrigunova didn’t know the exact reason for his dismissal, but added: “It was a cog that didn’t fit into any machine, and it had been that way since his childhood.”

After four months out of work, he became a soloist with the Birobidzhan Philharmonic Orchestra, telling local television: “If I don’t go to jail, join the army or get fired, then I hope to spend the next 12 years with you.”

“I do this for a reason”

Kushnir spent his free time protesting against the war.

In an email to a friend, he described posters put up around Birobidzhan at night with slogans angrily condemning the draft and describing Vladimir Putin as a fascist.

He also began hunger strikes: first for 20 days in the spring of 2023, and then for three months later that year.

Shkrigunova said Kushnir knew he was putting himself in danger.

“That was his only protest,” she said, “the behavior of a man who didn’t know what else to do.”

She tried to convince him to leave Russia, or at least perform in Berlin, where she now lives. But they were never able to arrange the trip.

In late March, Kushnir last spoke to Skrigunova, telling her that he felt like he was being watched and that he “kept seeing the same person.”

“Whatever happens, happens: I do it for a reason,” he added.

Operational reports/telegrams

Operational reports/telegrams“Like a skeleton”

There is no information about the criminal case against him in the records of the Birobidzhan Municipal Court, but there are records of a non-criminal case for “hooliganism” filed on 20 June.

On July 19, Kushnir was fined an undisclosed amount, but it was unclear whether he attended the hearing.

The court subsequently sent him a copy of the judgment, but it was returned on July 30 with the annotation “undeliverable.”

Of course, Kushnir was dead by then.

Independent news website Mediazona spoke to a person who met him shortly before his death.

They described him as “like a skeleton” who could barely walk by mid-July and was in “very bad condition”.

The official cause of death was “dilated cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure.”

The Financial Stability Board and the Birobidzhan Court did not respond to the BBC’s requests for comment. Vasily Mikhaylenko, the regional head of Russia’s prison service, told Mediazona he knew nothing about the case.

“Gentle and funny”

After Kushnir’s death, his mother told Okno, another independent news organization, that she tried to influence her son but failed.

“I would certainly like him to act in a quieter way and stay away from politics altogether.

“I’m sorry he gave up his life for what was clearly a pointless incident.”

But Shkrigunova disagreed, saying Kushnir always knew he was risking his life to express his anti-war views.

“He understood that there might be another way,” Skrigunova added.

“But when he realized that, there was no turning back. He knew he was going to go all the way, so it wouldn’t be in vain.

Kushnir received more attention after his death than during his lifetime.

A book he wrote in 2014 was quickly republished in Germany.

Grace Chatto, a member of Grammy-winning electronic music group Clean Bandit who studied with Kushnir at the Moscow Conservatory, took to Instagram to pay tribute to her “gentle and funny” Friends paid emotional tributes.

Twenty-two leading classical musicians, including Daniel Barenboim, Sir Simon Rattle and Martha Argerich, have written an open letter to commemorate a “remarkable artist” they had never met.

Although Kushnir’s YouTube channel only had single-digit subscriber numbers during his lifetime, his most popular videos have now been viewed more than 22,000 times.