Vedali Belushi,BBC News, London

Larkin Dooley

Larkin DooleyBack in September, art experts around the world were surprised when the name topped the latest list of the world’s best-selling artists.

Aboudia, a graffiti artist from Ivory Coast, beat established artists such as Damian Hirst and Banksy to become the artist with the most works sold at auction last year.

According to the Hiscox Artist Top 100, Aboudia, real name Abdoulaye Diarrassouba, has flogged 75 lots. One of the paintings sold for £504,000 (£640,000).

Leading online marketplace Artsy calls Aboudia a win “striking”while the Guardian said market experts “Caught off guard” By ranking.

A few months later, Abdia, sitting in a London gallery plastered with his paintings, told me the findings “didn’t come as a surprise” to him.

“Because if you work hard, success will come,” he said, wearing all black except for a wrist-full of beaded bracelets.

“First it’s your job…and then, it all comes home.”

Abdia’s subdued character clashes with the art around him – his brightly colored, richly layered canvases depict cartoon characters plucked from the streets of Abidjan, Ivory Coast’s largest city.

Through a mixture of recycled materials such as oil sticks, acrylic paint and newspaper, Abdia depicts the hardships of life in the center of Abidjan. He pays special attention to children who live and work on city streets.

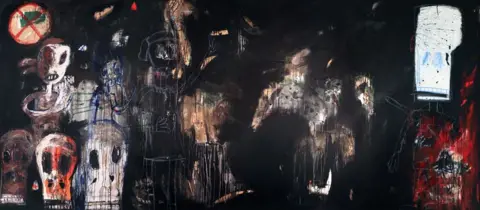

His eyewitness account of the 2011 civil war in Côte d’Ivoire is equally compelling. Characters stare at the viewer with blank eyes, while armed soldiers and skulls heighten the tension.

Today, there is a misconception that he “came very quickly,” Abdia said.

“No – I’ve been working on this for 15 or 10 years.”

Larkin Dooley

Larkin DooleyAbudia was born in 1983 in Abengourou, a small town about 200 kilometers (124 miles) from Abidjan. in a 2012 compositionThe artist said he was kicked out of the house when he was 15 after telling his father he wanted to paint for a living.

After being deported, young Abdia continued his efforts and entered art school. Lacking financial support, he slept in the classroom after other students went home. Those uncomfortable nights paid off – after graduating in 2003, the soon-to-be star was accepted into the École des Beaux-Arts, Ivory Coast’s top art school.

The School of Fine Arts in Abidjan will bring Abdia into contact with Ivorian art icons, whose influence can be found in his current work. Aboudia’s attention to the surrounding environment and use of recycled materials, for example, can be traced back to Vohou Vohou, a modernist collective founded in the 1970s by artists such as Youssouf Bath, Yacouba Touré and Kra N’Guessan.

Abdia began to deviate from traditional artistic styles, instead using wild brushstrokes and earthy colors to recreate the graffiti created by poor children in Abidjan.

In Abdia’s words, these young, de facto street artists “paint their dreams in the world.”

He says children are his main influence, rather than the widely-known American graffiti artist-turned-painter whose work is often likened to.

“When I started working, I didn’t know [Jean-Michel] Basquiat,” Abdia said.

“It’s not like: ‘There’s a guy named Basquiat, there’s a guy named Picasso,’ because schools don’t have internet and they don’t talk about those artists.”

After establishing his core style, Abdia would drag his paintings around the galleries in downtown Abidjan, hoping to find a way out.

“It was difficult… They would say: ‘Are you crazy? What kind of job is this? You’d better go to London, America or Paris because this job… doesn’t make sense here’,” Abdia recalled.

Abdia/Lajndure

Abdia/LajndureThe adversity didn’t end there. In 2010, then-Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo refused to step down after losing an election to rival Alassane Ouattara. Civil war broke out, killing 3,000 people and forcing another 500,000 from their homes.

During the four-month conflict, Abdia sought refuge in his basement studio, documenting the horrors he witnessed while venturing above ground.

The war ended with Mr Gbagbo’s dramatic capture by UN- and French-backed troops, and Abdia emerged from his refuge with 21 disturbing paintings.

Art lovers and journalists from Côte d’Ivoire and beyond praised his work, and Abdia began to achieve global success.

He was supported by renowned art collectors Charles Saatchi and Jean Pigozzi and continued to exhibit his work at prestigious venues such as Christie’s New York and the Venice Biennale.

Abdia’s first solo exhibition was at Larkin Durey (then known as Jack Bell Gallery) in London.

Owner Oliver Durey, who has known Abdia for more than a decade, told the BBC: “There is something in his paintings that we can all relate to; underlying uncertainty and terror. is a moment of balance of strength and beauty.

Henrika Amoafo, an expert on African art, said Abudia’s art “somewhat fits the international idea of Africa representing war and other forms of conflict.”

There are other reasons for his success, though, such as his “authenticity, the really raw emotional power that he’s able to convey, the way he talks about urban life, the way he talks about conflict and its impact on children,” she said of Amoafo, Senior Director of ADA Contemporary Art Gallery in Ghana.

Abdia/Lajndure

Abdia/LajndureAbudia’s rise also coincides with the rise of the African art market. Art analytics company ArtTactic reports that auction sales of contemporary and modern art from Africa surged 44% in 2021, reaching a record high of $72.4 million (£56.9 million).

ArtTactic also found that the global art market fell by 18% last year, while Africa only fell by 8.4%.

In its 2024 industry assessment, Hiscox does not rank best-selling artists by sales of all art as it did in 2023.

However, it ranks Abdia as the sixth most successful artist when it comes to works selling for less than $50,000 (£39,300).

Abdia’s rise has led him to split his time between his birth country and New York. When he returned to Côte d’Ivoire, he channeled his efforts into the Abdia Foundation, an organization he launched to support children and young artists in the country.

It’s another example of the star’s drive – but when I asked him if he had any plans for his career, he responded candidly: “No, I don’t.”

When I pressed him, he said he took it one day at a time—perhaps a soothing antidote to more than a decade of tenacity.

You might be right too.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC