Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn Friday morning, a 31-year-old female trainee doctor retired to sleep in the seminar room after a tiring day at one of India’s oldest hospitals.

This was the last time she was seen alive.

The next morning, her colleagues found her half-naked body with multiple injuries on the podium. Police later arrested a hospital volunteer allegedly in connection with the rape and murder at Kolkata’s 138-year-old RG Kar Medical College.

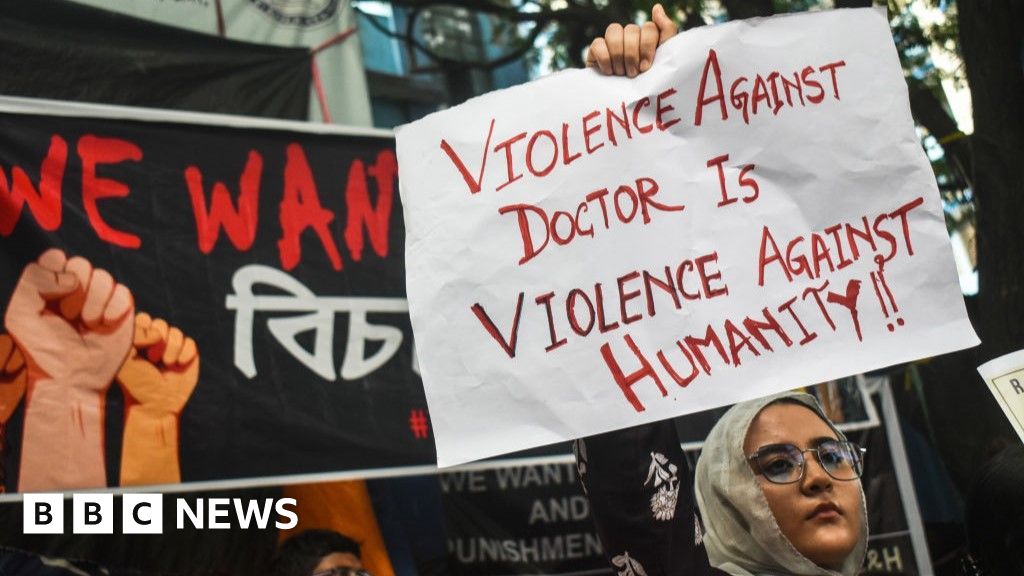

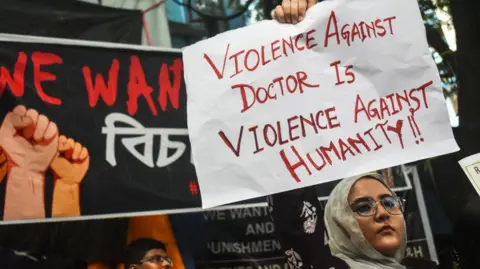

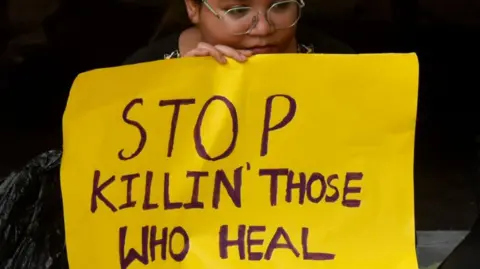

Angry doctors have gone on strike in the city and across India, demanding strict federal laws to protect health care workers. The tragedy has once again shone a spotlight on violence against health care workers in the country.

female makeup Nearly 30% of Indian doctors and 80% of nursing staff. They are also more vulnerable than their male colleagues. Official data shows disturbing Crimes against women increased by 4% By 2022, more than 20% of these incidents involved rape and assault.

Crime incidents at Kolkata hospitals last week exposed alarming security risks faced by many state-run medical institutions in India.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt RG Kar Hospital, which sees more than 3,500 patients a day, overworked trainee doctors, some working up to 36 hours straight, have no designated break room, forcing them to rest in a seminar room on the third floor.

Reports indicate that the arrested suspect, a patient volunteer with a troubled past, had unrestricted access to the ward and was captured on CCTV. Police claimed there was no background check on the volunteer.

Madhuparna Nandi, a junior doctor at Calcutta’s 76 Hospital, said: “The hospital has always been our first home; we just come home to rest. We never thought it would be so unsafe here. Now, After this incident we were scared.

Dr. Nandy’s own experience highlights how female doctors in India’s public hospitals are willing to work in conditions that put their own safety at risk.

The hospital where she worked was an obstetrics and gynecology residency, and there were no designated lounges or separate bathrooms for female doctors.

“If the patient or nurse allows me, I will use their toilet. When I work late, I sometimes sleep on an empty patient bed in the ward, or in the cramped waiting room with a bed and basin,” Dr. Nandy told me.

She said she felt unsafe even in the room where she rested after a 24-hour shift, starting with outpatient shifts and continuing through ward rounds and delivery wards.

One night in 2021, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, some men broke into her room, touched her, woke her up and asked her to “get up, get up. Look at our patients.”

“I was completely shocked by this incident. But we never thought it would get to the point where the doctor was raped and murdered in the hospital,” Dr. Nandy said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat happened on Friday was not an isolated incident. The most shocking case remains the Aruna ShanbaugA nurse at a prominent Mumbai hospital was left in a vegetative state after she was raped and strangled by a ward attendant in 1973. Recently, in Kerala, Vandana Das, A 23-year-old trainee doctor was stabbed to death with surgical scissors by a drunk patient last year.

In overcrowded government hospitals with unrestricted access, doctors often face the wrath of patients’ families following deaths or demands for immediate treatment. Anesthesiologist Kamna Kakkar remembers a tragic incident that occurred while working the night shift in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a hospital in the northern Indian state of Haryana during the 2021 coronavirus pandemic.

“I was the only doctor in the ICU when three men in the name of politicians forced their way into the ICU and demanded a much-needed controlled substance. I surrendered to protect myself because I knew my patient’s Safety is at risk,” Dr. Kaka told me.

Namrata Mitra, a Kolkata-based pathologist who studied at RG Kar Medical College, said her father, a doctor, often accompanied her to work because she felt unsafe.

Getty Images

Getty Images“During my shift, I took my father with me. Everyone laughed, but I had to sleep in a room hidden in a long, dark corridor with a locked iron door, where only patients came Only when the nurse can open it,” Dr. Mitra wrote in a Facebook post over the weekend.

“I’m not ashamed to admit I was scared. What if someone on the ward – a nursing staff, or even a patient – tried something? I took advantage of the fact that my dad was a doctor, but not everyone has that This kind of privilege.

When Dr. Mitra was working at a public health center in a district in West Bengal, she spent the night in a dilapidated one-story building that was used as a dormitory for doctors.

“Starting at dusk, a group of boys would gather around the house and make obscene comments as we came in and out to deal with emergencies. They would ask us to check their blood pressure as an excuse to touch us, and they would look out through the broken bathroom window. Look,” she wrote.

A few years later, while on emergency duty at a government hospital, “a group of drunk men passed by me, causing a ruckus, and one of them even touched me,” Dr. Mitra said. “When I tried to file a complaint, I found the officer dozing off with a gun in his hand.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSaraswati Datta Bodhak, a pharmacologist at a government hospital in West Bengal’s Bankura district, said the situation has gotten worse over the years. “My two daughters, both young doctors, told me that the hospital campus was infested with anti-social elements, drunkards and touts,” she said. Dr. Bodak recalled seeing a man with a gun roaming around a top government hospital in Kolkata during one visit.

India lacks strict federal laws to protect health care workers. RV Asokan, president of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), a doctors’ group, told me that while 25 states have some laws in place to prevent violence against them, criminalization is “almost non-existent.” “There is almost no security in the hospital,” he said. “One of the reasons is that no one thinks of hospitals as conflict zones.”

Some states, such as Haryana, have deployed private security guards to beef up security at government hospitals. 2022, federal government States are asked to deploy well-trained security forces to sensitive hospitals, install CCTV cameras, set up quick response teams, restrict access to “undesirable individuals” and file complaints against offenders. Apparently, nothing happened.

Even the protesting doctors don’t seem to have much hope. “Nothing will change… the expectation is that doctors should work around the clock and tolerate abuse as the norm,” Dr. Mitra said. “It’s a depressing thought.”