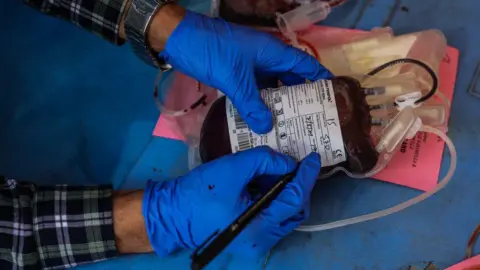

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2018, India’s Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling decriminalizing homosexuality, but the country still does not allow transgender people and gay and bisexual men to donate blood.

LGBT people say the decades-old ban is “discriminatory” and have taken to court to challenge it.

When Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli’s mother was battling late-stage Parkinson’s disease on her deathbed, she required regular blood transfusions.

But Ms Mowgli, a transgender woman living in the southern city of Hyderabad, is unable to donate blood despite being her mother’s sole caregiver.

“I have to keep posting [requests for blood donors] The process was “painful,” she said.

Ms Mowgli was lucky to find a donor for her mum, but many others were not.

Beoncy Laisharam, a doctor in the northeastern state of Manipur, recounted the experience of one of her patients whose transgender daughter was unable to donate blood for his treatment.

“Dad needs two to three units of blood a day. They can’t find blood from other sources,” she said.

“He died two days after he was brought in.”

It was stories like this that prompted Sharif Ragnerka, a 55-year-old writer and activist, to file a petition with India’s Supreme Court against a ban on LGBT people donating blood.

Indian law prohibits LGBT people from donating blood on the grounds that they are at high risk for HIV – donors must be suffering from the disease that can be transmitted through blood transfusions.

The policy dates back to the 1980s, when several countries implemented similar bans to control the raging HIV/AIDS epidemic that killed thousands of people around the world.

Despite the change in attitudes, subsequent policies have retained the ban, including the latest rules drafted in 2017.

The complaint, filed in July, argued that the existing blood donation policy is “highly prejudicial and presumptive” and violates the LGBT community’s fundamental rights to “equality, dignity and life.”

The court has asked the federal government to respond to Mr Ragnarkar’s request, linking it to two similar court cases filed in 2021 and 2023 that are currently pending before the court.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt an earlier hearing, the government defended the ban by citing a 2021 Department of Health report that said transgender, gay and bisexual men were “six to 13 times more likely to be infected with HIV than the general population.” “.

“Government policy is to reduce risks, without moral judgment [attached to] It,” said blood transfusion specialist Dr. Joy Maman.

But critics say the policy is discriminatory and rooted in shame, leaving them feeling “ostracized and insignificant”.

“There are HIV-positive people of other genders, but their entire communities are not banned [from donating blood]”, said Dr Biancsi, adding that the ban reinforced existing stereotypes.

There are estimated to be tens of millions of LGBT people in India. In 2012, the Indian government estimated its population at 2.5 million, but global estimates suggest the true number may be more than 135 million.

Many of them face discrimination and are forced to leave their families.

Activists said the ban prevented them from accessing vital medical services because it prohibited them from collecting blood from partners or “selected families”.

“If there is a total ban on LGBT people donating blood, how do you expect community members to get help in emergencies?” asked LGBT activist Sahil Choudhary.

In many cases, donors may also feel the need to lie about their sexual orientation when filling out mandatory blood donation forms in order to save the life of a loved one.

Activists argue that the ban, in addition to being discriminatory, is also unjustified because of the high demand for blood transfusions in the country.

one study A 2022 report from the Public Library of Science estimated that India faces a shortage of about 1 million units of blood every year.

Transgender rights activist Thangjam Santa Singh, who petitioned the court against the ban last year, said India’s current laws are outdated as some countries have lifted restrictions on LGBT blood donors in recent years.

Last year, the United States lifted all restrictions on gay and bisexual men donating blood. Now, donors are no longer screened based on their sexual orientation, but based on whether they engage in “high-risk sexual behavior.”

All potential donors must answer a questionnaire about their recent sexual history. Those who have had a new sex partner, multiple sex partners and those who have had anal sex within the past three months are asked to wait three months before donating blood.

The rationale is that new testing technology can detect HIV cases more quickly, so potential blood donors can donate blood safely based on their personal risk assessment.

The UK has similar guidance in place in 2021.

The petitioners believe that India should also establish an individual-centric blood donation system based on “actual risk” rather than “perceived risk”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMs Singh said the Indian government could consider setting deferral periods based on a donor’s recent sexual history, rather than denying the entire LGBT community the opportunity to donate.

“It makes me feel like I’m not human,” she said.

The Indian government objects to this and says the country’s healthcare system is not ready for change.

In its response to a petition filed earlier in the Supreme Court, the federal government said advanced blood testing technology, such as nucleic acid tests that are widely used in other countries, are available in India in only a “small subset” of blood banks.

“In India, the system is not strict enough,” Dr. Maman said.

He added that this applies not only to “testing” but also to “ensuring an environment of privacy and confidentiality so that people feel comfortable answering questions about their sexual history”.

But community members are unconvinced and say they will continue to oppose the “biased ban”.

“I kept thinking how could I not donate blood if my family had an emergency need,” Mr. Ragnaka said.

“I don’t want to spend the rest of my life trying to figure out how to get around these obstacles.”