go through Gene McKenzie, BBC News, reporting from Kyiv

BBC/Tanyarat Doksone

BBC/Tanyarat DoksoneA corner of Kiev’s iconic central square is now covered with thousands of small blue and yellow flags to commemorate Ukraine’s fallen soldiers. Earlier this month, a group of activists came together to add different types of flags to the growing collection. They have unicorns at the center to represent every gay soldier killed in the war.

Death of Ukrainian LGBT soldier exposes inequalities. They do not have the same rights as heterosexual troops. Same-sex marriage is illegal, meaning that when these soldiers are killed, their partners have no right to decide what happens to their bodies or receive state support.

Rodion, a 30-year-old costume designer, came to plant a flag in memory of his ex-boyfriend Roman, who was killed in the early months of the invasion and the day before his 22nd birthday.

Roman and five others from his brigade were killed in a missile attack near Kupiansk, near Kharkov, after a local family tipped off their location to the Russians.

“All this death, all this blood, it’s the same whether you’re straight or gay,” Rodion said, before he was suddenly interrupted by the familiar sound of air-raid sirens.

“See?” he continued, pointing to the sky. “Missiles can kill us just like they kill everyone else.” The war injected urgency into the fight for equality. “I’ve been waiting for 30 years, and I can’t wait another 30 years because I have no guarantee that I’ll be alive when this is over,” Rodion said.

Handouts

HandoutsAttitudes toward LGBT rights have shifted dramatically over the past decade as Ukraine has embraced European values, although many still hold socially conservative and even homophobic views.

Openly gay people fighting and dying on the front lines further challenged people’s prejudices. But meaningful change is hard to see.

A bill to allow same-sex couples to enter into civil partnerships was introduced to Parliament last spring amid high hopes, but 14 months later it has stalled.

Meanwhile, LGBT soldiers report being bullied and harassed in their units.

In 2022, when Mariya Volya almost died defending her hometown of Mariupol, now occupied by Russia, she decided it was time to take a stand.

Although the 31-year-old has been serving in the military since 2015, a full-scale Russian invasion has left her fearful and shifting. She is no longer afraid to reveal her sexuality.

Mariah posted about her coming out on the LGBT Soldiers TikTok account. When her commander saw the post, he told her to delete it. She subsequently received a flood of hateful comments online from anti-LGBT activists. Maria was transferred to the army and now works in the Donetsk region near the Eastern Front as a radio engineer for the 47th Brigade.

But she still had to respond to discriminatory comments. “Why can’t you form your own army?” some of her comrades asked. She continued to be harassed online and on the street, and sometimes felt unsafe going out in military uniform to avoid being recognized.

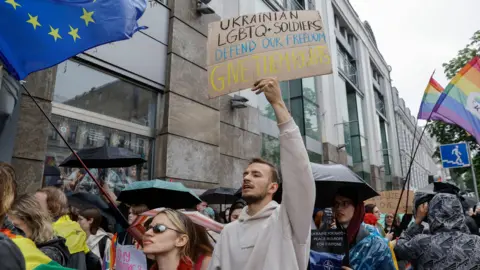

But on June 16, while taking a break from the front lines, Maria donned khaki camouflage pants and participated in the first Pride parade in Kiev since the invasion began.

Maria, joined by her fiancée Diana, joined the choir in chants of “Victory and Equality”. “We have two demands. More weapons and civilian partnerships,” organizers shouted.

Legalizing same-sex marriage is currently not possible because it would require amending the constitution, which was not possible during martial law in Ukraine.

“I can’t rule out the possibility that something serious happened and I want my fiancée to be taken care of and protected,” Maria said.

As she spoke, Diana shifted uncomfortably and looked away. “I don’t like when you talk like that,” she said.

But Diana knew the risks. Maria could hear explosions in the background as she called her from the front. “We want to stay in touch as much as possible, but I won’t tell her what I’m going through,” Maria said, admitting it would be too scary for her.

Maria and Diana were joined by about a dozen LGBT soldiers in the pouring rain. For some, this was their first Pride parade and they received special permission from the commander to attend the day’s events. This is unthinkable in 2021.

EPA/Sergey Dorzhenko

EPA/Sergey DorzhenkoOne couple used the parade to visit family and troops. “This is a very emotional day for us,” they told me, not yet ready to reveal their names publicly. “We are proud to be able to show people that we have a lot of gay soldiers and that we are on the front lines defending Ukraine. .

The BBC has asked the Ukrainian military about the treatment of LGBT soldiers but has yet to receive a response.

Much of the work to raise the profile of LGBT soldiers on the front lines has been done by Viktor Pylypenko, the first openly gay soldier in the Ukrainian army who came out about his sexual orientation in 2018.

The combat medic started an online community to encourage serving soldiers to share their experiences on Instagram because he noticed that when he told people he rescued from small frontline villages that he was gay, they often became more accepting.

“People’s attitudes are changing because they have heard our stories. For example, there are many gay soldiers operating air defense systems in Kiev, and people are very grateful to them,” he said.

Victor acknowledged that Vladimir Putin, whose commitment to promoting traditional family values has incorporated homophobia into his ideology, reached out to his community. Ukrainians tried every means to resist him.

“This is a battle of values, and people understand that if we want to continue to be integrated into Europe, to join the EU, to join NATO, then we should embrace liberal values,” Victor said.

EPA/Sergey Dorzhenko

EPA/Sergey DorzhenkoBut despite this, opposition to change remains fierce. Pride events are tightly policed, partly to avoid being targeted by Russia, but also because of the danger posed by anti-LGBT groups, which disrupt the parade every year. Only 500 people are allowed to attend.

Confined to a small patch of sidewalk that had been cordoned off and surrounded by police cars, the marchers walked only a few dozen steps before being taken underground and into the subway, where far-right counter-protesters swarmed in, shouting violent threats. Same insulting slogans.

“The people who oppose us, although small in number, are loud and increasingly active,” Victor said before boarding the train. Returning to the ground, he felt unsafe.

A similar situation is playing out in Parliament. The civil partnership bill has been rejected by a committee of MPs following pressure from church leaders, according to Inna Sovsan, the lawmaker who introduced the bill last year. In parts of Ukraine, religious beliefs fuel homophobia.

Ms Sofsan said: “Unfortunately what we are seeing is that parliament is more conservative than society and that instead of listening to the public, politicians are responding to the church, which is not the majority but is very vocal. “.

BBC/Tanyarat Doksone

BBC/Tanyarat DoksoneA member of the Legal Affairs Committee, where the bill is currently on hold, told the BBC that the majority of committee members opposed the legislation and were guided by the concerns of the church and its constituents.

Assemblymember Mykola Stefanchuk said the bill’s supporters are now trying to win over opponents.

LGBT soldiers and activists are now coming to terms with the possibility that the war may not provide a window for the change they hope for.

The day after the parade, Victor felt uncomfortable. He was convinced that homophobic protests were a thing of the past. But Maria and Diana were disillusioned.

When the bill was first introduced, Maria wrote hopeful letters to her MPs. But as the process dragged on, she said, she gave up.

“I think it’s going to be a long road.”

Additional reporting by Thanyarat Doksone, Hanna Tsyba and Anastasiia Levchenko