Mike Juma sat on the end of the bed in his ninth-floor one-bedroom apartment in downtown Los Angeles, staring out the window at the mountains visible.

“I don’t like tall buildings,” he said. “But look at that beautiful view. It’s what they call the million-dollar view.

A year ago, 64-year-old Juma’s life changed dramatically. He lived in a tent in the slum, made money selling cigarettes, and slept with a samurai sword by his side for protection.

Now, he’s in a furnished apartment, listening to the soft hiss of the air conditioner.

Last year, Juma was among a group of homeless people moved from slums into temporary and permanent housing. It’s part of a $280 million county plan to house more than 2,500 people and promote health, medication and related services in the 50-block community, which has become poor and homeless. A synonym for return.

Mike Juma shows off his kitchen in the Weingart Tower in downtown Los Angeles, where he moved in early August.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

The initiative, known as the Ghetto Action Plan, is also an effort to combat the systemic racism that drives people to Skid Row – where there are large numbers of black people – by trying to transform the neighborhood into a thriving community. Taking over sidewalks and campsites.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes Skid Row, initiated the project, which launched a year ago after months of planning and organizing. So far, the county has moved nearly 1,000 homeless people into permanent housing and nearly 2,000 into shelters, according to recent data released by the county Healthy Housing Program, which leads the program. and temporary housing such as transitional housing.

According to the 2022 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count, there were 4,402 homeless people on Skid Row when the program launched, with more than half living in tents or temporary shelters. Today, the population is 3,791, a decrease of nearly 14%.

“We’re very concerned about this,” said Elizabeth Boyce, deputy director of healthy housing. “We’re sticking to the key elements of tackling homelessness and what we know we can achieve.”

The progress comes as counties and cities are facing pressure to: Governor Gavin Newsom Cleaning up homeless encampments Supreme Court ruling That said, cities can enforce laws that restrict homeless encampments on sidewalks and other public property. The upcoming 2028 Olympics will make matters worse.

Solis praised the agency and its partners for their quick turnaround.

“Our goal is to provide permanent housing to 2,500 people within three years, and one year into the program we are more than a third of the way there,” Solis said in an email. “A crisis in favelas is already brewing It will take many years for us all to work together to address this issue, focusing on prevention, early intervention and the provision of evidence-based treatment services.”

Government officials have long tried to address Skid Row homelessness. For example, in the early 1970s, supporters of development wanted to demolish much of the area, while others advocated retaining the area’s low-income housing and services as a way to keep slum dwellers in the slums. , which is called a “containment plan.”

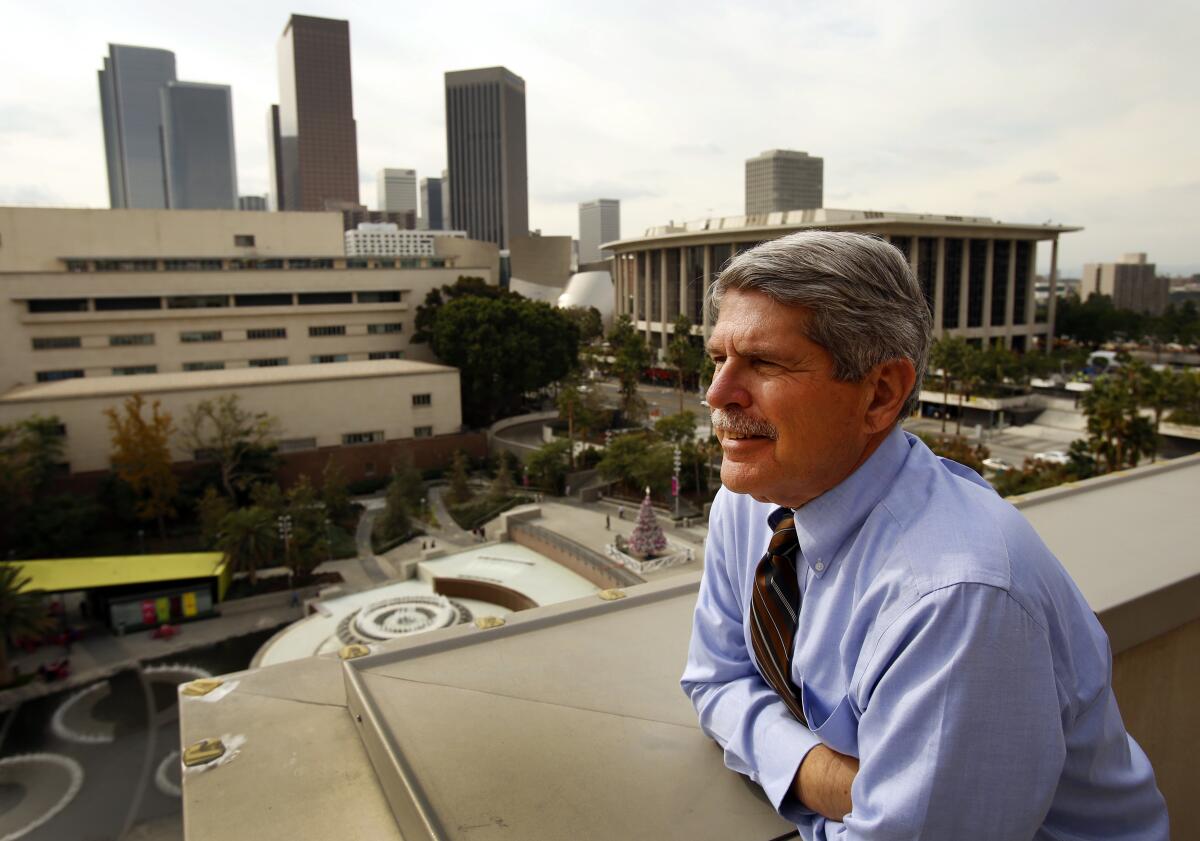

Zev Yaroslavsky in downtown Los Angeles in 2014.

(Alseb/Los Angeles Times)

Launched in 2007 by then-director Zev Yaroslavsky Item 50a pilot program that aims to provide housing to 50 chronically homeless people in Skid Row through a Housing First approach. He tried to expand it but unsuccessful.

Boyce said the Slum Action Plan is unique in that it aims to address the complex needs of the community with the help of slum residents, service providers and other stakeholders. It also leverages resources the county already uses to address the region’s homelessness crisis.

“We’ve been thinking from the beginning,” she said, “how do we create thoughtful, compelling change…not in the people who live there, but in the support that people receive.

“You’ve got to get some wins early and show you’re talking business.”

In June 2023, Housing for Health and its partners, the City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority were awarded $60 million in state grants The project is funded until 2026.

Boyce said the funds were critical to the program’s early success. They helped build 350 new temporary housing units and 750 new permanent units, and increased and improved outreach services.

The funds also helped establish a “safe landing” in the lobby of the Cecil Hotel; people can come at any time of the day or night to receive medical and housing services. The funding also creates a program specifically to help Skid Row providers get temporary housing to clients as quickly as possible.

County officials say their work is far from over. They plan to establish a Habitat Advisory Committee to oversee key areas of the Slum Action Plan. In addition, they want to establish a harm reduction health center that would provide drug testing and detoxification beds and provide services such as referrals to rehabilitation centres. There are also plans to set up a safe field area – a large outdoor park in the slum where people can visit and engage with various agencies for government benefits and schemes.

Juma stares out the window from his room on the ninth floor of Weingart Tower 1.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Last week, Juma lit a cigarette on the ninth floor of the Weingart Building.

“It’s like getting used to the smell of a new car,” he said of his new digs, his voice cracking. This is “different”.

Juma’s tower is located in the slum and includes 228 studios and 47 one-bedroom apartments. At least 40 units are reserved for veterans. Juma served in the Marine Corps.

How Juma ended up on the streets is unclear. He said he once had a cross-country trucking business, delivering fish. Due to money and tax problems, he ended up losing his business and everything that came with a stable job.

A liking for alcohol was one reason, although he said it wasn’t a factor.

When he became homeless, he said he returned to an area he was familiar with. He set up his tent near Sixth Street and Towne Avenue, not far from the seafood shop.

He said he’s gotten used to living outdoors, even if it’s difficult at times. At night, he rarely fell asleep to the sounds of people screaming, loud music, and fighting. Then there’s the early traffic of commercial trucks.

“You heard everything,” he said. “You are like a blind man who cannot sleep when he hears footsteps.”

Last year, he said he was ready to get off the streets after injuring a man in a fight. Standing next to the bleeding man, he said he knew he’d had enough.

“I almost killed him,” he said. “I’ve had a lot of fights; sometimes you come out the winner, but you never really win.

So he contacted Healthy Housing’s outreach workers. They quickly found him a temporary home. He then applied for supportive housing and waited several months. A week ago, he was told an apartment was available for him.

Mike Juma, who served in the Marine Corps, has a new home in Skid Row.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

He said he had been sleeping for three days since moving into his new apartment. Behind him on the bed was a brown pillow with the words: “God has not forgotten me.”

Juma said the apartment comes with a new refrigerator, stove, TV and, happily, a bathroom. He said the kitchen cupboards were filled with plates, pots and cooking utensils.

But the windows are the most symbolic feature of his new home. As he contemplates future possibilities, he can glimpse into his past life. He said that from high up in his room he could see the street where he lived in the tent.

Sometimes, he said, he looks down and thinks: “It finally worked out.”