go through Samir Hashmi, BBC Middle East Business Correspondent News

Shutterstock

Shutterstock“They can keep saying it and we can keep proving them wrong.”

This was the response of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in a TV documentary aired in July 2023, when he spoke of doubts about Saudi Arabia’s flagship construction project.

Nearly a year later, some of the doubts have been proven correct.

In recent months, Saudi Arabia has appeared to scale back plans for its massive desert development, Neom, which is a centerpiece of Vision 2030.

It is an economic diversification plan spearheaded by Prince Mohammed, the de facto ruler of the Gulf state, to wean the country’s economy away from dependence on oil.

In addition to Neom, Saudi Arabia is developing 13 other large-scale construction schemes, or “megaprojects,” worth trillions of dollars. These include an entertainment city on the outskirts of the capital Riyadh, multiple luxury island resorts on the Red Sea and a range of other tourist and cultural destinations.

But low oil prices have hit government revenues, forcing Riyadh to reassess those projects and explore new financing strategies.

An adviser with links to the government, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told the BBC the projects were under review and a decision was expected soon.

“The decision will be based on a variety of factors,” he said. “But there will undoubtedly be a recalibration. Some projects will go ahead as planned, but some may be delayed or scaled down.

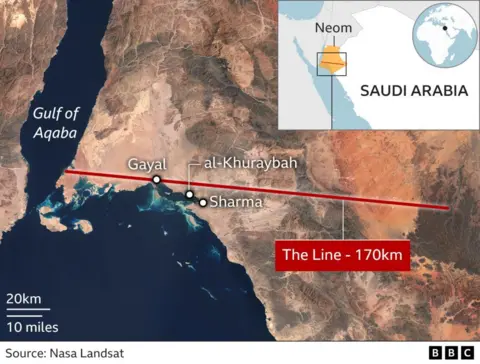

Announced in 2017, Neom is a $500bn (£394bn) plan to build 10 future cities in the desert region of the country’s northwest.

The most ambitious of them all and grabbing all the headlines is The Line. It will be a linear city consisting of two adjacent, parallel skyscraper walls, 500m high, taller than the Empire State Building. However, including the gaps between them, their total width is only 200m.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe original plan was to extend 170 kilometers (105 miles) and become home to 9 million residents.

But according to people familiar with the details (as already revealed to the media), project developers will now focus on completing the 2.4 kilometers of work by 2030 as part of the first module.

When The Line was first announced, it was billed as a “carbon-free linear city” that would redefine urban living, offering residents amenities such as parks, waterfalls, flying taxis and robot maids.

The city will have no roads or cars and will be made up of interconnected pedestrian communities. It also includes ultra-fast trains with a maximum journey duration of 20 minutes anywhere within the city limits.

How many of these features will be part of the first phase is unclear.

In addition to The Line, Neom plans to include an octagonal floating industrial city and a mountain ski resort that will host the 2029 Asian Winter Games.

Ali Shihabi, a former banker who now sits on Neom’s advisory board, said the goals set for the project under Vision 2030 were deliberately “overly ambitious by design.”

“It was inherently overambitious and it became clear to us that only part of it would be delivered on time. But even that part was important,” Mr Shehabi said.

Neom’s downsizing has put the financing challenges facing the Saudi Arabian government into focus.

Neom is funded by the Saudi Arabian government through its sovereign wealth entity, the Public Investment Fund (PIF).

The official cost of construction of Neom is $500 billion, 50% higher than the country’s entire federal budget for this year. But analysts estimate that executing the entire project will ultimately cost more than $2 trillion.

Saudi Arabia’s government budget has been in deficit since late 2022, when the world’s largest oil exporter began slashing production to accelerate rising global oil prices. The government projects a deficit of $21 billion this year.

The PIF is feeling the pressure. It controls about $900 billion in assets but had only $15 billion in cash reserves as of September.

Raising funds for Neom and other large programs is a key challenge ahead, said Karen, the former International Monetary Fund managing director in Saudi Arabia and now a visiting fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute.

“It will become increasingly challenging to fund the PIF to the levels required for these projects,” Mr Cullen said.

The Gulf state is using other avenues to shore up capital.

Earlier this month, the company sold about $11.2 billion worth of stock in its national oil company, Saudi Aramco. Much of the proceeds are expected to flow into PIF, which was also the biggest beneficiary when the company went public in 2019.

The sale comes amid volatile oil prices. In July last year, the Saudi-led OPEC+ group of oil producers restricted output in an effort to boost prices.

Riyadh voluntarily reduced supply by 1 million barrels per day. However, this month OPEC+ reversed this decision and will gradually begin to increase production starting in October.

According to the International Monetary Fund, Saudi Arabia needs a barrel of oil worth $96.20 to balance its budget. Brent crude oil prices, one of the main benchmarks for crude oil, have been hovering around $80 a barrel.

The country also relies on selling government bonds to keep the PIF’s funds flowing. Another challenge is that foreign direct investment remains well below targets, underscoring Riyadh’s difficulty in attracting funding from private businesses and international investors.

“It will be very difficult to convince investors to take part in what they consider to be an overly ambitious plan,” Mr Cullen said. “It’s unclear where your returns ultimately come from.”

The Gulf state has also poured money into sectors such as tourism, mining, entertainment and sports as part of its economic diversification strategy.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has won the right to host many major international events such as the 2027 Asian Football Cup, the 2029 Asian Winter Games, and the 2030 World Expo, and has become the only country to bid for FIFA in 2034. All of these projects will require significant investment in the coming years.

Mr Shehabi expects the government will prioritize these international events as they approach. “Our projects that have specific deadlines will be prioritized based on the nature of the matter,” he said.

In April, at a special meeting of the World Economic Forum in Riyadh, the country’s Finance Minister Mohammed al-Jadaan said that the government had no “ego” and would adjust its Vision 2030 plan as needed to transform the economy.

“We’re going to change direction, we’re going to extend some projects, we’re going to scale down some projects, we’re going to accelerate some projects,” he said.