About a decade ago, Andrew Thorpe received a text message from the crew of a small plane flying overhead: They had discovered a new methane hotspot.

Thorpe drove a hulking rental SUV along winding dirt and mountain roads near the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. Sure enough, methane was seeping out of the ground, most likely from a leaking pipeline.

He found a sign in the desert with the phone number of a gas company, so he called them. “The person on the other end of the phone is the person I’m most confused about,” Thorpe said. “I tried to explain to them why I was calling, but this was many years ago and there wasn’t any technology to do that.”

Over the years, Thorpe’s work has attracted some unwanted attention. “I did some driving investigations in California … and a for-hire police officer was very suspicious of me and tried to scare me off,” Thorpe said. “If you put a thermal camera on a public road and point it at a tank outside the fence, people will get nervous. I’ve been heckled by some oil and gas workers, but that’s normal.

Today, Thorpe is a member of the greenhouse gas monitoring frontline team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Flintridge, La Canada. For more than 40 years, JPL’s Microdevices Laboratory has developed specialized instruments to measure methane and carbon dioxide with extremely high precision.

These instruments, called spectrometers, detect gases based on the color of sunlight they absorb. Earlier this year, a team of researchers from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, and the research nonprofit Carnegie Science Selected as a finalist Received NASA award to launch technology into orbit.

Technicians at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory are working on the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS), which will be installed on aircraft to search for methane and other greenhouse gases.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

If a satellite mission is chosen, the team’s carbon survey, dubbed “Carbon-I,” would launch in the early 2030s. Over the course of three years, Carbon-I will continue to map global greenhouse gas emissions and take daily snapshots of areas of interest, allowing scientists to identify sources of climate pollution such as power plants, pipeline leaks, farms and landfills.

While there are already several satellites monitoring these gases, Carbon-I’s resolution is unprecedented and will eliminate any guesswork in determining where the gases are being emitted. “What’s undeniable is that once we see the plume, there are no other potential sources,” said Christian Frankenberg, Carbon-I co-principal investigator and professor of environmental science and engineering at Caltech. .

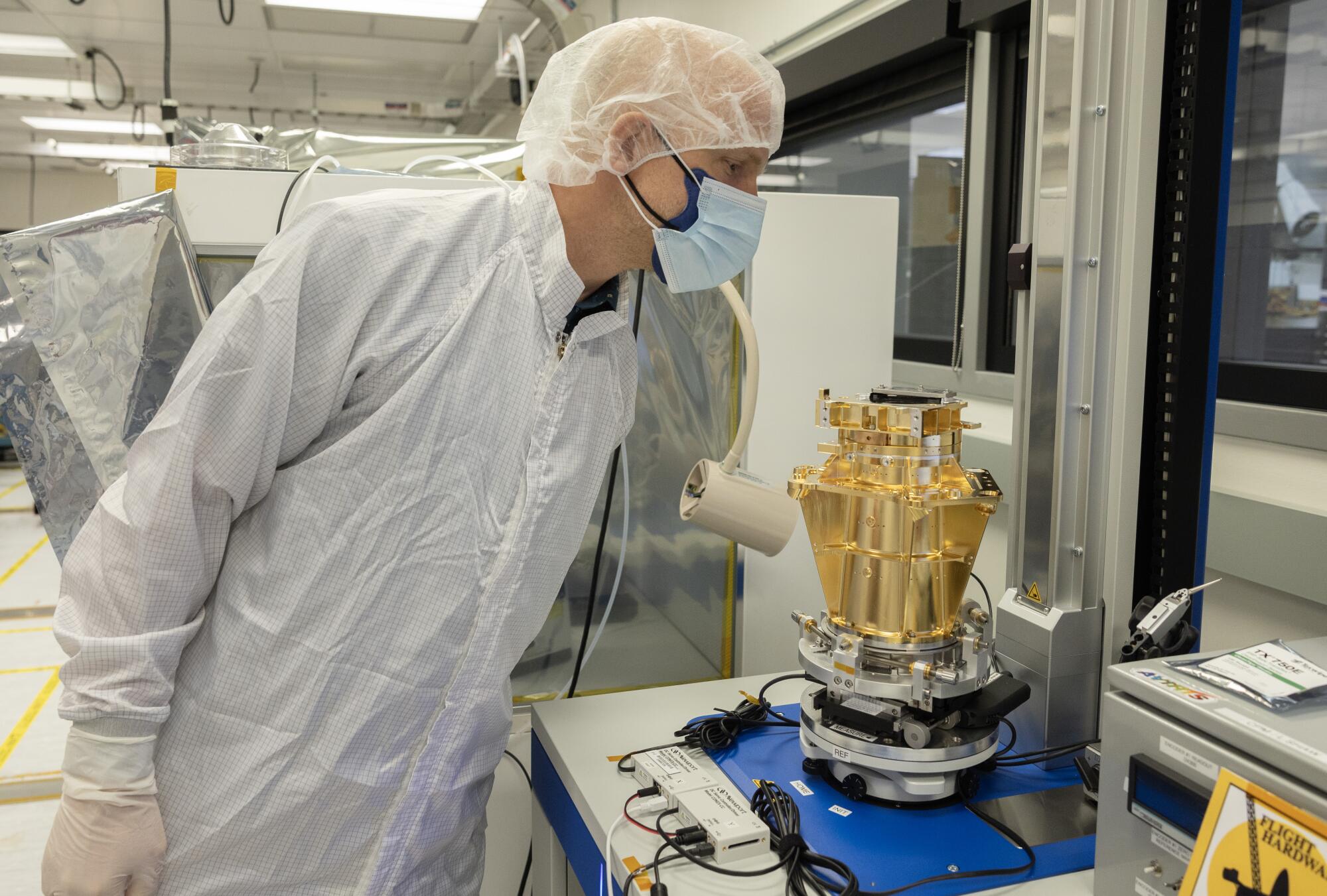

Caltech professor Christian Frankenberg, co-principal investigator of the proposed space-based carbon-emissions monitoring system, looks at the AVIRIS monitor being built at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory laboratory.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

With an optimal resolution of 100 feet, Carbon-I “is very high resolution from space. It’s an incredible solution,” said Debra Wunch, a professor at the University of Toronto who studies Earth’s carbon cycle and Not involved in the Carbon-I proposal. “It will give us a deeper understanding of the source of emissions… It will be groundbreaking. You can even see individual stacks, individual parts of the landfill.”

Historically, monitoring greenhouse gas emissions from a single emitter has been a challenge – both carbon dioxide and methane are colorless and odorless. As a result, scientists often must rely on adding together a company’s self-reported value and the study’s estimates. For example, to estimate the amount of methane produced by dairy cows, scientists must determine the amount of methane released by one cow and multiply it by the total number of cows on Earth.

“If you look at international policies … right now they are all based on these bottom-up checklists,” said Anna Michalak, founding director of Carnegie Science’s Carnegie Center for Climate and Resilience and co-principal investigator of Carbon-I. “We need to get to the point where … we actually have an independent way of tracking emissions.”

Carbon-I’s resolution will also provide scientists with new insights into the tropical atmosphere, where clouds currently obscure most forms of satellite surveillance. “That’s their Achilles’ heel,” Frankenberg said.

Because tropical and subtropical forests absorb About a quarter of the carbon dioxide human generation Accurate data from this part of the world is urgently needed due to the burning of fossil fuels.

The lower-resolution satellites currently orbiting Earth cannot see through small gaps in cloud cover. They can only see a blurry average of the dark and clear spots for each pixel in the sky. With each pixel area nearly 50 times smaller than most other satellites, Carbon-I can see into open spaces and measure through them. in a April 2024 PaperFrankenberg, Michalak and their collaborators estimate that Carbon-I will see through clouds in the tropics 10 to 100 times more often than its predecessor.

Carbon-I “will see things where people don’t know what’s going on,” Thorpe said. “This will open up a whole new field of science.”

JPL’s airborne greenhouse gas monitoring program dates back decades, but the space-based monitoring field is still fairly new. In early 2016, NASA headquarters contacted the JPL team. There is a large-scale Blowout at Aliso Canyon natural gas storage facility Near Porter Ranch, NASA wanted the team to check it out.

The team flew over the site on a variant of a 1960s spy plane for three consecutive days over the course of a month while Southern California natural gas companies struggled to contain the blowout. Meanwhile, NASA’s Goddard Flight Center in Maryland pointed the Hyperion spectrometer on NASA’s Earth Observation spacecraft to the leak.

Hyperion is designed to observe the Earth’s surface and filter out atmospheric noise. Now, they’re trying to look at the atmosphere and filter out the surface, and for this firstscientists observed man-made methane point sources from orbit.

“The Hyperion results are very noisy, but you can still see the plume,” Thorpe said. “This really proves that we can do this from space.”

Even if Carbon-I launches, that doesn’t mean the team will stop placing instruments on the aircraft. The team was able to monitor areas of interest from the aircraft at a much clearer resolution for several days. Now, leaner, more streamlined versions of the spectrometers that observed the Four Corners leak and the Aliso Canyon blowout are flying on a series of missions to monitor emissions from offshore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico.

A twin-engine King Air aircraft used by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory conducts greenhouse gas monitoring flights in a hangar at Hollywood Burbank Airport.

(Noah Haggerty/Los Angeles Times)

The aircraft mission also gave the team a chance to try out new and improved spectrometers. “You can repair them, you can upgrade them,” said Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineer Michael Eastwood, who has worked with spectrometers for more than three decades and flies with them frequently. “You can take more risks than you would need to have a really mature, really well-known, high-reliability spacecraft — we’re not constrained by that.”

Air units are also agile. Typically, two crew members sit in the second row of a King Air twin-prop plane, looking at a stack of laptops and instruments with buttons that rival an airplane cockpit. They can view real-time GPS data and spectrometer results on the screen and coordinate flight plans with the pilot. The spectrometer, called AVIRIS, short for Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer, is located in the third row and looks down through a window in the floor.

Carbon-I was selected as a finalist for a NASA program to fund space and earth science that benefits society. The team received $5 million in funding to refine its project proposal ahead of final NASA review in 2025.

This two-step process for selecting missions is new to NASA’s Earth science program and requires JPL to compete with other members of the scientific community, independent of their relationship with the space agency.

“If we’re talking about grocery money, [$5 million] It may seem like a lot of money, but it’s actually a great deal. “If you think about you investing $300 million in a mission, it’s very smart to spend 1.5 percent of that to really make sure it’s going to be great and successful.”

At the same time, the Carbon-I team is committed to demonstrating to NASA that it has the technical know-how to execute the project on time and within budget.

“I think all four missions in this current phase are absolutely valuable science missions,” Michalak said. “For satellite missions, a 50 percent chance is not that bad.”

communication

Towards a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter on climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation and solutions.

From time to time you may receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.