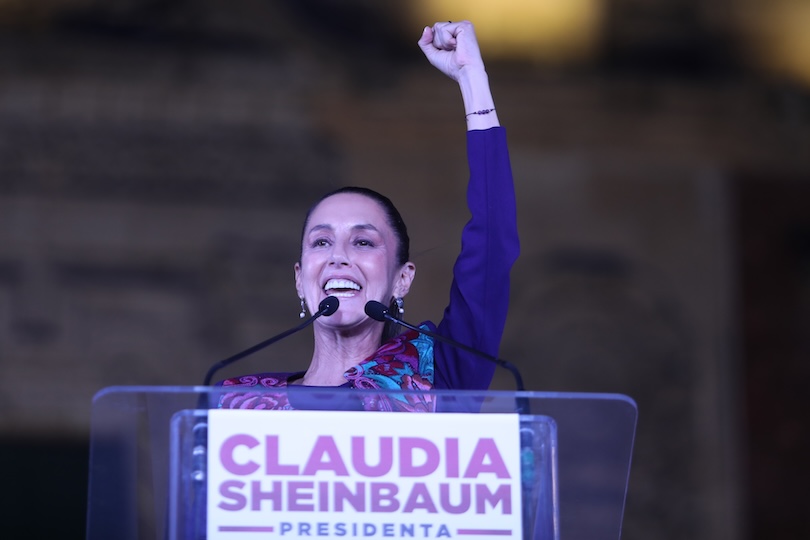

On June 2, Mexico elected its first female president, or as we say in Spanish, President. Mexico’s president-elect Claudia Sheinbaum has been praised globally for her sparkling credentials. She holds a Ph.D. She holds a PhD in environmental engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, co-authored the 2007 Nobel Prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, and was the first female elected mayor of Mexico City. She would also become the country’s first Jewish president. And, Sheinbaum didn’t just win. She won about 60% of the popular vote in a three-way election and led her party’s coalition to a historic victory, winning two-thirds of the seats in the lower house of Congress.

The election result fell just two Senate seats short of an absolute majority, allowing Sheinbaum and her party MORENA to pass constitutional reforms with little resistance from the opposition. So not only will Mexico have its first President Come next October, but it will also usher in the most powerful president in recent history. As president, Sheinbaum will have the opportunity to reshape the country and make a lasting impact. However, there is growing uncertainty about whether these changes are good or bad.

Scheinbaum’s mentor and former president Andres Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) is a controversial figure in Mexican politics, accused of promoting populism, embodying authoritarian tendencies and undermining the country’s democratic institutions. Despite these accusations, AMLO will leave office with a record high approval rating (66% as of April 2024). Sheinbaum has benefited politically from her long-standing loyalty to Obrador, and she has vowed to follow his vision for Mexico’s “fourth transformation.”

As part of Mexico’s so-called “fourth transition,” Obrador has pushed for harsh economic austerity measures, infrastructure development with irreversible consequences for the environment, and the economic and political empowerment of the military. Additionally, Obrador has repeatedly attempted to dismantle Mexico’s National Electoral Institute and National Transparency Institute — both considered cornerstones of Mexican democracy. Since the election, Morena lawmakers have said they will continue to seek constitutional changes to dismantle the two institutions and overhaul Mexico’s judiciary by subjecting Supreme Court justices to a popular vote.

Elect Mexico’s first president President This is not spontaneous or accidental, but intentional. Although Mexico has a poor record on gender-based violence, it is a notable example of promoting affirmative action for women, especially in politics. Mexican women were not allowed to vote until 1953. More than 60 years since Mexican women first voted, Mexico has adopted legal gender quotas of at least 50 percent in federal and state congresses, also known as gender parity. In 2019, Mexico furthered this goal by passing a constitutional reform known as “Equality for All,” which mandates equality “in the composition of all elected and appointed offices.”

As a result, in 2018, Mexico became the first and only country to achieve gender parity in both houses of Congress. Women also serve as presidents of both houses of Congress and the Supreme Court. They hold important positions of power, heading the Ministries of Citizen Security and Protection, Foreign Affairs and Interior. After the recent elections, women will hold 13 of the 32 governorships. Among them is incoming Mexico City Mayor Clara Brugada (also from MORENA). Nonetheless, it is important to note that increasing the representation and participation of women in positions of power is a necessary but not sufficient step towards achieving gender justice. Having a female president doesn’t necessarily translate into more feminist policies or automatic improvements in women’s lives. Furthermore, applying a critical feminist perspective means debunking essentialist explanations that are based on the assumption that women are inherently “good.”

Mexico’s worsening crisis of gender-based violence shows that gender equality does not automatically translate into gender justice. Despite women’s significant representation in Congress and government, 10 women are killed every day and 7 go missing. However, these statistics only show extreme violence against women and girls and obscure the everyday forms of gender-based violence they experience. A survey by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography found that 70% of Mexican women have experienced some type of gender-based violence in their lifetime, including psychological, economic, physical and sexual violence.

While serving as mayor of Mexico City, Sheinbaum repeatedly claimed that her policies helped reduce femicide by 30 percent. However, a closer look at the data reveals an increase in killings of women in “unidentified” cases, fueling speculation about whether the true number of female killings is being covered up. An article by financial aspects Found that femicide increased by 30%, not decreased. Likewise, the number of missing men and women has increased in Mexico City. However, Sheinbaum refused to acknowledge these facts and sought to minimize the number of missing persons during her term.

Another security-related challenge is militarization. Although Obradov campaigned in 2018 on a promise to remove the military from traditional civilian tasks such as public security, he has significantly expanded the military’s economic and political power. Still, there is evidence that militarization has failed to curb crime and insecurity since then-President Felipe Calderon declared a “war on drugs” in 2006 and deployed thousands of troops across the country. On the contrary, studies show that as militarization increases, homicides and human rights violations increase.

Scheinbaum, however, followed in the footsteps of Obrador and Calderon. In 2022, after the pandemic ended and residents complained of structural problems, Scheinbaum deployed 6,000 National Guard troops on the Mexico City subway. Sheinbaum also promoted and sanctioned police violence to suppress feminist protests. As a result, Sheinbaum’s relationship with feminist groups and collectives in the capital was particularly hostile and contentious.

As the first in Mexico President, Sheinbaum has made history. However, her legacy will be defined by five specific issues: climate change, immigration, economic policy, political reform and security. If she decides to side with Obrador, who favors environmentally damaging policies, austerity measures, democracy-weakening reforms and militarization, the consequences could be dire. There is hope, however, that Sheinbaum will decide to take matters into his own hands and instead implement a progressive policy agenda that prioritizes environmental, fiscal and gender justice.

Further reading on electronic international relations