A middle-aged man in Rhode Island took high-potency cocaine. In 2022, the state had the fourth-highest rate of cocaine overdose deaths in the nation.

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

hide title

Switch title

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

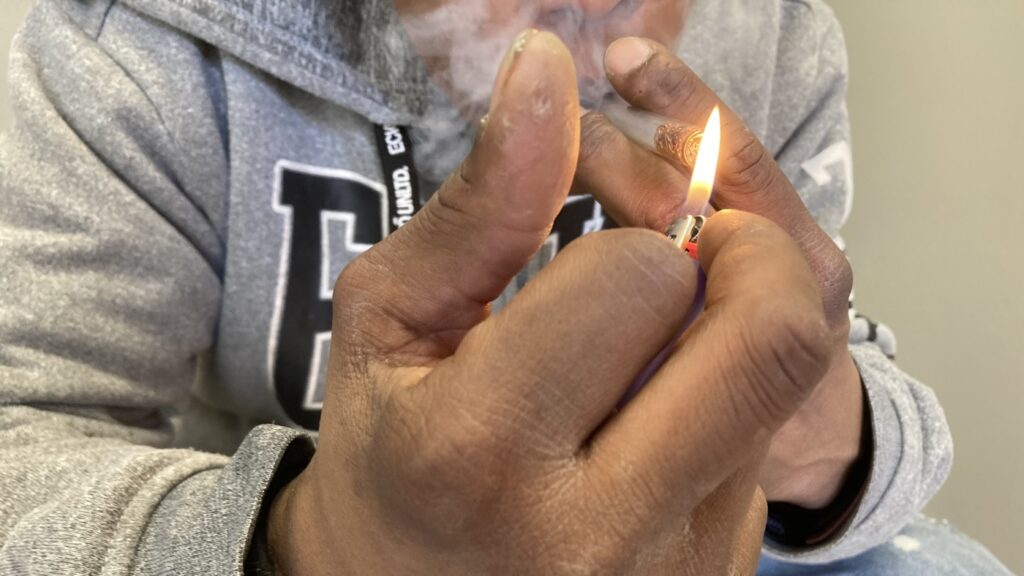

In Pawtucket, Rhode Island, near a storefront advertising “free” cell phones, JR sat in an empty back stairwell and showed reporters how he avoids an overdose while snorting crack cocaine.

(NPR is identifying him by his initials because he fears being arrested for using illegal drugs.)

It had been several hours since the last knock, and the talkative middle-aged man moved his hands quickly. In one hand he held a glass pipe. Another was lentil-sized crumbs of cocaine.

Or at least JR hopes it’s cocaine, pure cocaine – not tainted with any fentanyl, a powerful opioid that was linked to nearly 80% of overdose deaths in Rhode Island in 2022 .

He flicked the lighter to “test” his power source. He said if it had a “cigar-like sweetness,” it meant his cocaine contained “fentanyl,” or fentanyl. He put the pipe to his lips and took a tentative drag. “It’s not sweet,” he said reassuringly.

But the “method” he devised provides only false and dangerous assurances. It is virtually impossible to tell whether a drug contains fentanyl by taste or smell. One mistake can be fatal.

“Someone can believe they can smell it [fentanyl] “Either taste it, or see it…but it’s not a scientific test,” said Dr. Josiah “Jody” Rich, an addiction expert and researcher who teaches at Brown University. “People are dying today because they buy They had some cocaine, but they didn’t know it contained fentanyl.”

The mix of stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 times more powerful than heroin, is driving what experts call the “fourth wave” of the opioid epidemic. This mixture poses a significant challenge to overdose reduction efforts because many stimulant users are unaware that they are at risk for ingesting opioids and therefore do not take overdose prevention measures.

The only way to know if cocaine or other stimulants contain fentanyl is to use a drug-checking tool like a fentanyl test strip — a harm-reduction best practice currently being used by federal health officials to combat drug overdose deaths. Fentanyl test strips sell for as little as $2 a pack online, but many frontline organizations also provide them for free.

Test kit for detecting the potent opioid fentanyl in cocaine samples.

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

hide title

Switch title

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

The first wave of the long and devastating opioid epidemic in the United States began with the misuse of prescription painkillers (early 2000s); the second wave involved increased heroin use, starting around 2010.

The third wave began around 2015, when powerful synthetic opioids such as fentanyl began to appear in the supply.

Now experts are observing the fourth phase of this deadly epidemic. Nationwide, illegal stimulants mixed with fentanyl are the most common drugs in fentanyl-related overdoses, according to a 2023 study published in the journal Science addiction.

The stimulant in this deadly mix tends to be cocaine in the Northeast and methamphetamine in the West and much of the Midwest and South.

“The leading cause of drug overdose deaths in the United States is the combination of fentanyl and stimulants,” said Joseph Friedman, a researcher at UCLA and the study’s lead author.

“Black and African Americans have been disproportionately affected by this crisis, especially in the Northeast.”

Factors Contributing to Multiple Drug Overdose

It’s unclear how much of the latest trend in polydrug use is accidental or intentional. A recent study from Millenium Health found that most people who use fentanyl sometimes do so intentionally and sometimes unintentionally.

Friedman said people often use stimulants to quickly withdraw from fentanyl. The high-risk practice of using cocaine or methamphetamine with heroin, known as “speedballing,” has been around for decades.

Other factors include manufacturers adding cheap synthetic opioids to stimulants to extend supply, or dealers mixing up bags.

But researchers say many people in Rhode Island still believe they are using pure cocaine or crack — a misconception that can be deadly.

Stimulant users unprepared for fentanyl’s ubiquity

“People who use stimulants without intentionally using opioids are unprepared to deal with an opioid overdose… because They don’t think they’re in danger.

Researchers surveyed more than 260 drug users in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, including some who manufacture and distribute stimulants such as cocaine.

More than 60 percent of the people they interviewed in Rhode Island had purchased or used stimulants that they later discovered contained fentanyl.

In 2022, Rhode Island ranked fourth in cocaine overdose death rates, behind only Washington, D.C., Delaware and Vermont. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

People who use opioids infrequently have lower tolerance, which puts them at higher risk for overdose.

Many of the people interviewed in the study also used the drug alone, so if they overdosed, it might not be discovered until it was too late.

Jennifer Dubois was a single mother whose 19-year-old son, Clifton, died of a drug overdose in 2020. The counterfeit Adderall pills he took contained the powerful opioid fentanyl.

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

hide title

Switch title

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

Du Bois was a single mother raising two black sons. Her eldest son, Clifton, had been battling drug addiction since he was 14, she said. Clifton has also been diagnosed with ADHD and mood disorders.

DuBois said that back in March 2020, as the pandemic intensified, Clifton had just entered a rehabilitation program.

Clifton was upset about not being able to visit her mother because of the lockdown at the rehab center. “He said, ‘If I can’t see my mom, I can’t get treatment,'” DuBois recalled. “I begged him” to continue treatment.

But soon after, Clifton dropped out of the rehab program. He showed up at her door. “I just cried,” she said.

Du Bois’s younger son lived at home. DuBois did not want Clifton to take drugs around his brother. So she gave Clifton an ultimatum: “If you want to stay home, you have to stay away from drugs.”

Clifton went first to stay with family and friends in Atlanta and later in Woonsocket, an old factory city with the highest overdose death rate in Rhode Island.

In August 2020, Clifton overdosed but regained consciousness. DuBois said Clifton later revealed that he and a friend were smoking cocaine in the car.

Hospital records show he tested positive for fentanyl.

“He was really scared,” DuBois said. After the overdose, she said, he tried to “stop using cocaine and hard drugs.” “But he’s taking his meds.”

Eight months later, on April 17, 2021, Clifton was found unresponsive in a bedroom at a family member’s home.

The night before, Clifton bought fake Adderall, according to the police report. What he didn’t know was that Adderall pills contained fentanyl.

“He thought he would be better off staying away from street drugs … and just taking pills,” DuBois said. “I do believe Cliff thought he was taking something safe.”

In 2023, friends of Jennifer Dubois posted a memorial advertising billboard in downtown Woonsocket, Rhode Island. The ad features her 19-year-old son, Clifton, who died of a drug overdose in 2020.

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

hide title

Switch title

Lynn Aditi/Public Radio

The opioid epidemic is driving up mortality among older black Americans (ages 55-64) and, more recently, among Latinos, according to a recent study published in the American Journal of Medicine. American Journal of Psychiatry.

But focusing solely on the presence of fentanyl is an oversimplification, said study author Joseph Friedman, a researcher at the University of California, San Diego.

For years, hospitals have safely used medical-grade fentanyl to treat surgical pain because its potency is tightly regulated.

“It’s not the strength of fentanyl that’s dangerous,” he said. “In fact, the potency of drugs on the illicit market fluctuates greatly.”

He said studies of street drugs show that the potency of fentanyl in illegal drugs ranges from 1 to 70 percent.

“Imagine ordering a mixed drink at a bar and there’s anywhere from one to 70 in it,” Friedman said. “The only way you know is to start drinking it…There’s going to be a lot of alcohol overdose deaths.”

Drug-checking technology can give a rough estimate of fentanyl concentrations, but getting a precise measurement requires sending the drug to a lab, he said.

Fentanyl test strips provide a low-cost method to prevent overdose by detecting the presence of fentanyl, regardless of potency, in cocaine and other illicit drugs.

In Rhode Island, harm reduction organizations like Weber/Renew provide free testing kits.

But test strips only work if people use them — don’t take the drugs if they test positive for fentanyl. And not enough people dope.

This story comes from NPR’s health reporting partnership public broadcaster and KFF Health News.