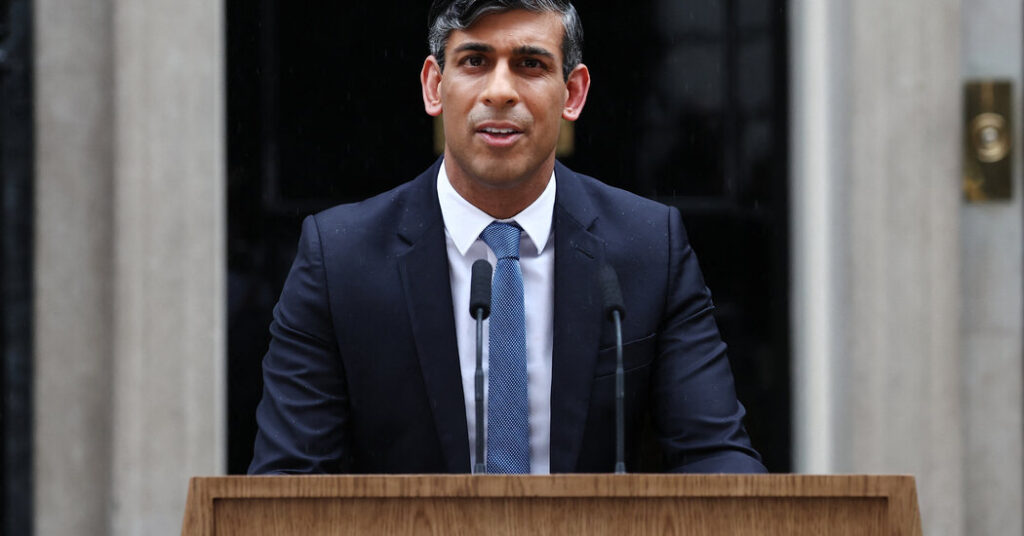

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called a snap general election for July 4 on Wednesday, leaving the fate of the embattled Conservative Party in the hands of a restless British public that appears hungry for change after 14 years of Conservative government.

Sunak’s unexpected statement from a rain-soaked podium in front of No. 10 Downing Street became the starting gun for a tense six weeks of campaigning that will challenge President Barack Obama. The ruling comes from the party that has led Britain since becoming US president. But the Conservatives have ditched four prime ministers in eight years and are reeling from the chaos of Brexit, the coronavirus pandemic and a cost-of-living crisis.

The opposition Labor Party has led by double digits in most opinion polls over the past 18 months, making the Conservatives’ defeat inevitable. Still, Mr Sunak believes Britain has received enough good news in recent days – including the dawn of new economic growth and the lowest inflation in three years – that his party may be able to hang on to power.

“Now is the time for Britain to choose its future,” Mr Sunak said as steady rain soaked his suit. “You have to choose in this election who has this plan.”

Political analysts, opposition leaders and members of Sunak’s own party agree that the electoral mountain he must climb is the Himalayas. Burdened by a recession, soaring prices, disastrous trickle-down tax cuts, and a series of scandals and malfeasance, the Conservative Party has appeared tired and adrift in recent years, divided by bitter internal fighting and a fatalism about the future.

“The Conservative Party is facing an extinction-level event,” said Matthew Goodwin, a professor of political science at the University of Kent who has advised Boris Johnson and other party leaders. “It looks like they are going to suffer a bigger defeat than Tony Blair did in 1997.”

Other political analysts are more cautious: some note that in 1992, Prime Minister John Major’s Conservative government overcame a severe polling deficit to win by a narrow margin and remain in power.

But since the party’s landslide victory in the 2019 election on the slogan “Get Brexit Done”, the Conservatives have lost support among young people, traditional Conservative voters in the south and southwest of England, and working-class voters in industry. Midlands and northern England, their support in 2019 was key to then Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s landmark victory.

Many are disappointed with Mr Johnson, who was forced to step down after a scandal that included a Downing Street party breaking coronavirus lockdown rules, and even more so with his successor, Liz Truss. After the shock, she was overthrown after just 44 days.

Although Sunak, 44, quickly stabilized markets and ran a more stable government than his predecessor, critics say he never developed a convincing strategy to boost the country’s economy. He also failed to deliver on two other promises: to reduce NHS waiting times and to stop small boats carrying asylum seekers from crossing the English Channel.

Many voters in “red wall” constituencies – named after Labour’s campaign colours – appear ready to return to their political roots in the party. Under the able (if uncharismatic) leadership of Keir Starmer, Labor has emerged from the shadow of its left-wing predecessor, Jeremy Corbyn. Former government prosecutor Starmer methodically overhauled the Labor Party, purging Corbyn’s allies, rooting out vestiges of anti-Semitism within the party and moving its economic policies closer to the centre.

Under British law, Sunak must hold an election by January 2025. But after announcing on Wednesday that annual inflation had fallen to 2.3%, just above the Bank of England’s 2% target rate, he may have gambled that the economic news would be as good as expected.

Sunak may also be calculating that the government could launch the first flights carrying asylum seekers to Rwanda next month. It would allow him to claim progress on another key priority – stopping small boats carrying asylum seekers from crossing the English Channel.

Rwanda’s policy of deporting asylum seekers to African countries without first hearing their cases has been condemned by human rights activists, courts and opposition leaders. It has also prompted a series of legal challenges. But Sunak has made it central to the government’s agenda because it is popular with the Conservative political base.

For Sunak, whose parents are of Indian origin and immigrated from British colonial East Africa sixty years ago, the decision to go to the electorate earlier than expected is not entirely out of character. In July 2022, Sunak resigned as chancellor and broke with Johnson, triggering a loss of cabinet support and ultimately forcing Johnson to step down.

Subsequently, Sunak actively ran for the party leadership, but lost to Truss in a vote of the party’s approximately 170,000 members. After Ms Truss’s economic policies backfired and she was forced to resign, Mr Sunak re-emerged and won a contest held only among Conservative MPs.

Sunak inherits a daunting set of problems: unemployment, economic stagnation and rising interest rates, which are affecting people in the form of higher mortgage rates. After years of austerity, NHS waiting times have stretched to weeks and even months.

Sunak had some early successes, including a deal with the EU that largely defused the trade impasse in Northern Ireland. He exceeded his goal of halving the inflation rate, which was 11.1% when he took office in October 2022.

At the beginning of the year, Britain emerged from a shallow recession surprisingly strong, with the economy growing by 0.6%. The International Monetary Fund raised its growth forecast for the country this year while praising the government and central bank for their actions.

But this may only be a brief moment of good news. Inflation is expected to rebound again in the second half of this year, and April’s data was not as low as economists expected. That has led investors to reconsider how soon the Bank of England might cut interest rates, all but ruling out a rate cut next month. Even expectations for a rate cut in August have waned.

Meanwhile, the scope for further tax cuts ahead of the election has deteriorated. Data released on Wednesday showed an increase in public borrowing. The International Monetary Fund this week warned the government against cutting taxes, arguing that Britain urgently needs to increase public spending and investment to improve public services such as health care, while also stabilizing public debt.

Ultimately, analysts say, it is these trends that have prompted Sunak to decide to go to voters now on issues that will determine his and his party’s political fate.

“You can talk about partygate and Truss,” said Tim Bell, a political science professor at Queen Mary University of London, referring to Johnson’s lockdown-breaking social gatherings. “But ultimately, what will decide this election is lack of growth and a country that is collapsing before our eyes.”

Ashley Nelson Contributed reporting.