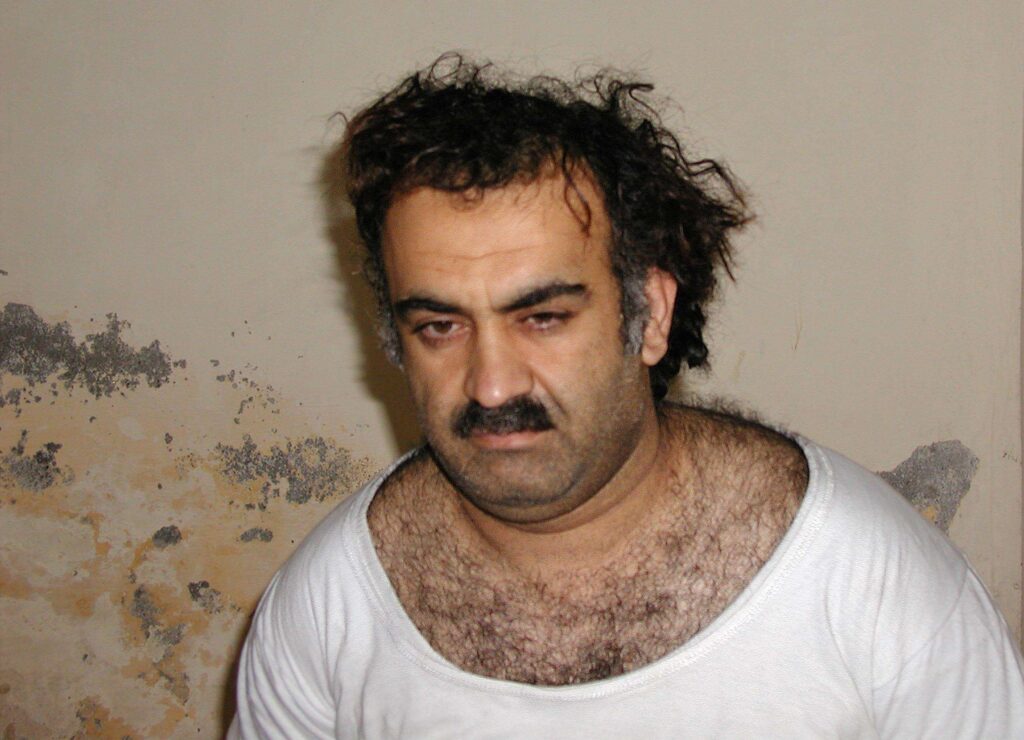

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and two other al-Qaeda members behind the 9/11 attacks pleaded guilty to 2,976 counts of murder, US military prosecutors revealed in a letter to the families of 9/11 victims on Wednesday. In exchange, the 9/11 planners would escape execution. The letter called the plea agreement “the best path to ultimate outcome and justice in this case.”

Mohammed and his associates were first detained by the United States in 2003. Mohammed admitted to television reporters a year before his arrest that he planned the attacks. So why, more than two decades later, is a plea deal reached in a secret military court the best the U.S. government could do?

This is a self-inflicted problem. Instead of letting law enforcement deal with the massacre on U.S. soil, President George W. Bush locked suspects in secret torture prisons, forever tainting the evidence. Confessions and any statements made under torture will not be admitted in any court. back Lawyers can also challenge torture. After all, some known innocent people also confessed under torture.

When the Obama administration sought to put Muhammad on trial in New York, the scene of his crimes, politicians from both parties helped stoke public outrage. Congress passed a bipartisan law preventing al-Qaeda suspects from being transferred to U.S. soil. Instead, Mohammed and the other defendants were tried by a military tribunal in Guantanamo Bay that was neither fair, transparent nor swift in delivering justice. This is the worst situation in the world.

Many of the victims’ relatives were blindsided by the plea deal.

“9/11 family members feel betrayed right now,” Brett Eagleson, president of the nonprofit 9/11 Justice, told reporters. spy talk, a substack focused on national security. “We were not consulted in any way about what was going to happen at Guantánamo.”

The guilty plea of the 9/11 planners was one of many missed opportunities to end the war on terror. After killing al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, the Obama administration could have declared victory and begun the process of moving on. Instead, he promised endless war.

“His death does not mark the end of our efforts,” U.S. President Barack Obama said when announcing bin Laden’s death. “There is no question that al Qaeda will continue to launch attacks against us. We must and will remain vigilant at home and abroad.”

This “overseas vigilance” means a war against an ever-changing alphabet soup of Islamist rebels, most of whom have nothing to do with 9/11 and some of whom did not exist when the war on terror began. The American public is confused about what they are fighting for or against. As Rep. Sara Jacobs, D-Calif., pointed out at a hearing last year, even the list of groups the U.S. government considers “al Qaeda affiliates” is classified.

At the same time, an ongoing sense of siege corroded U.S. domestic politics. Counter-terrorism has become an excuse for police militarization. Obama-era defenses of drone strikes are being reincorporated into anti-immigration conspiracy theories. Concerns about “radicalization” and “extremism” are used to drive online censorship.

“Tools that destabilize foreign countries must also destabilize the United States,” journalist Spencer Ackerman wrote in his 2020 book. Reign of Terror. “To experience neither peace nor victory for such a sustained period is a precarious situation for millions of people.”

All the while, it’s easy to forget that the people who sparked all the fear in the first place—the perpetrators of 9/11—are either dead or in prison.

Perhaps Bush and Obama’s decisions are understandable, if not excusable, because the trauma of 9/11 remains so deep. But these decisions prevented the wound from healing. Twenty years on, the closest thing to “finality and justice” is a sad, quiet compromise.