go through Katia Adler, European Editor

Getty Images

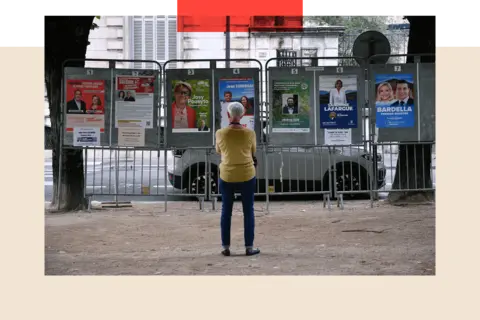

Getty ImagesWhat are the chances that France will wake up to a new far-right dawn on Monday morning?

The garish and hotly debated scene dominated media headlines, the EU in Brussels and the seats of European governments after the first round of voting in the French parliament last week.

Despite the performance of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (RN) party, the simple answer is: an RN majority is possible. Not too possible.

France’s centrist and left-wing parties strategically withdraw candidates to back each other’s rivals ahead of election Sunday’s decisive second-round match.

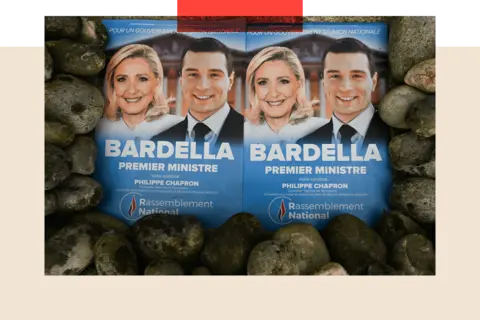

But regardless of whether RN wins an absolute majority, and whether the young president Jordan Bardella, who is savvy with social media, becomes France’s new prime minister, the impact of this election will be huge.

Polls predict Republicans are almost certain to win more seats than other political groups.

This means that a decades-old taboo in France, the core country of the European Union, will be broken.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe European Union was born out of the ashes of the Second World War. It was originally designed as a peace project with wartime enemies France and Germany at its core.

Far-right parties have been driven to the margins of European politics.

Last month, world leaders gathered in northern France to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the D-Day invasion of Normandy, where the Allied forces launched an amphibious assault that helped defeat Nazi Germany.

But now, “extreme right”, “extreme right” or “populist nationalist” parties have become part of coalition governments in a number of EU countries, including the Netherlands, Italy and Finland.

There are challenges in labeling these parties. Their policies change frequently. They also vary from country to country.

Their normalization is not an entirely new phenomenon. Former Italian Prime Minister and centre-right politician Silvio Berlusconi is the first EU leader to take such action. As early as 1994, he formed a government with the post-fascist political group “Italian Social Movement”.

Six years later, Austria’s conservatives formed an alliance with the far-right Freedom Party. At the time, the EU was so outraged that it blocked official bilateral contacts with Austria for months.

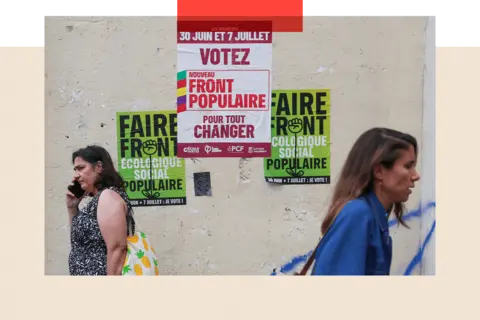

Postwar political etiquette dictates that the political mainstream must form a health warning linea “health barrier” to keep far-right elements out of European governments during elections.

The generally recognized term for this practice is “french”, which gives you a sense of how passionate many French people are about it.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring the 2002 presidential election, some French voters held clothespins to their noses on the way to the polls to show that they would vote for a candidate they didn’t really like, just to keep the far right out.

It is a far-right wing led for years by Marine Le Pen’s father and which includes former members of France’s Nazi-led Waffen SS.

Fast forward to 2024, and Marine Le Pen’s decade-long ambition to change the name of her father’s party and work to clean up its image appears to be a resounding success.

this health warning line A deep rift is now emerging after the leaders of France’s centre-right Republicans and the National Party agreed not to compete against each other in specific constituencies on Sunday. This is an earthquake in French politics.

Crucially for Marine Le Pen, those who support her are no longer ashamed to admit it. RNs are no longer seen as an extremist protest movement. For many, it offers a credible political platform, no matter what its critics claim.

French voters trust Republicans more than other parties to manage the economy and (currently poor) public finances, according to an Ipsos poll for the Financial Times. This is despite the party’s lack of experience in governing and its tax cuts and spending plans being largely unfunded.

Which begs the question when you observe the anxiety and despair in European liberal circles about the growing success of the so-called “New Right”: if traditional legislators served their constituents better, perhaps there would be less chance of European populism How do activists get in?

By populists, I mean politicians like Ms Le Pen who claim to listen and speak on behalf of “ordinary people” and defend them against the “establishment”.

This “them and us” argument works well when voters are anxious and ignored by the governing powers. Just look at Donald Trump in the US, the sudden breakthrough of British reformists in Thursday’s UK election and the runaway success of Germany’s controversial anti-immigration party Alternative for Germany.

In France, many see President Macron – a former commercial banker – as arrogant, privileged and distant from the day-to-day affairs of ordinary people outside the Paris bubble. They say this man has made an already difficult life even harder by raising the national pension age and trying to raise fuel prices, citing environmental concerns.

Frustratingly for the French president, his success in lowering unemployment and the billions of euros he has spent to mitigate the economic impact of the coronavirus and energy crisis appear to have been largely forgotten.

Meanwhile, the Republican campaign has focused largely on the cost-of-living crisis.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe party promised to cut gas and electricity taxes and raise the minimum wage for low-income earners.

Its supporters insist that priorities such as these mean registered nurses should no longer be labeled a far-right movement. They point to the party’s growing support base and say the party should not forever be tainted by its racist roots under the elder Le Pen.

A similar statement was made in Rome. Italian Prime Minister Giorgio Meloni once praised fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. Her Italian Brothers party has post-fascist roots, but she now leads one of the EU’s most stable governments.

She recently denounced a meeting of the party’s youth wing. Members were filmed giving fascist salutes. She said there was no room in her party for nostalgia for the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century.

While domestic critics warned of attempts by Italian media to influence the country’s media landscape and warned of Ms Meloni’s attacks on LGBTQ+ rights, her concrete proposals to tackle irregular migration have won praise from mainstream Europe, including European Commission President Ursula Ursula. Ursula von der Leyen and recent British proposals to address irregular migration.

Frankly, on hot-button issues such as immigration, it is increasingly difficult to distinguish the political rhetoric of Europe’s far right from the deliberately strident rhetoric of traditional mainstream politicians trying to retain voters.

Former Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte is a prime example, as is Emmanuel Macron, who grew increasingly aware of Marine Le Pen’s popularity.

One of the unintentional effects of mainstream politicians further emulating political parties on immigration is that it makes the original anti-immigration parties look more respectable, more acceptable, and more electable.

Witness the stellar performance in the recent Dutch election by anti-immigration politician Geert Wilders, who is often accused of hate speech.

The label “far right” is one that requires debate. Much depends on the composition of the parties.

But the recognition that Ms Meloni now enjoys in wider international circles remains a distant dream for Ms Le Pen.

The registered nurse insists she is still on track to gain a parliamentary majority this Sunday. Polls suggest a paralyzed hung parliament or an unruly coalition government with non-Le Pen parties is more likely.

All of this would make Macron a rather lame president.

Domestic political instability means that large EU countries such as France and Germany are turning inward at a time of great global uncertainty.

The war in Gaza and Ukraine is raging. Donald Trump, who is skeptical of the EU and NATO, may return to the White House.

These are precarious times for a leadershipless Europe. Voters feel exposed.

Even if it’s not this Sunday, Marine Le Pen’s followers are convinced that their time is coming. soon.

BBC in-depth report is the new home of websites and apps delivering the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a unique new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and in-depth coverage of the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. We’ll also be showcasing thought-provoking content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer. We start small but think big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking the button below.