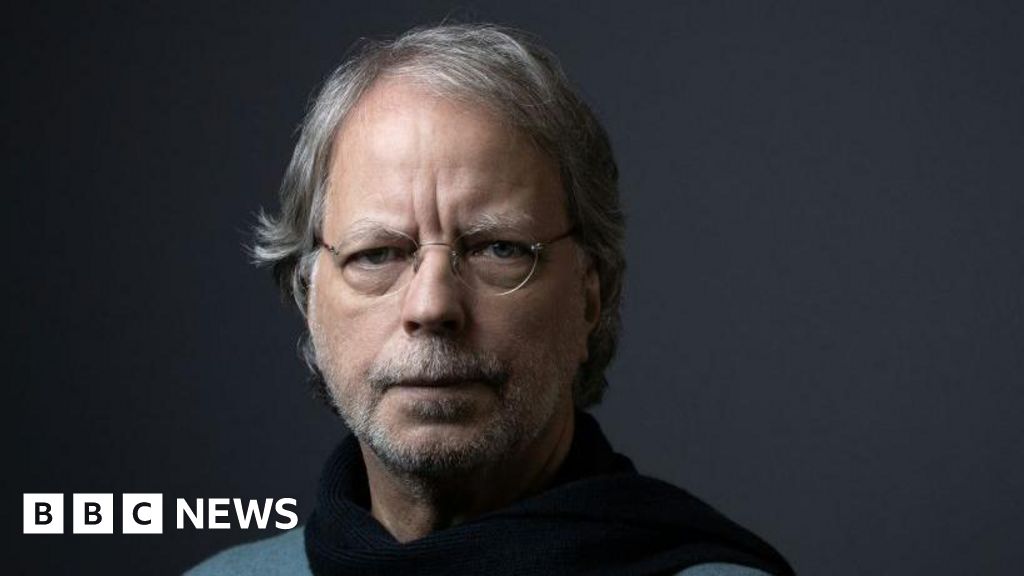

Getty Images

Getty ImagesInternationally renowned author and poet Mia Couto describes herself as African, but his roots are in Europe.

His Portuguese parents settled in Mozambique in 1953 after escaping the dictatorship of Antonio Salazar.

Cotto was born two years later in the port city of Beira.

“I had a very happy childhood,” he told the BBC.

He noted that he was aware that he lived in a “colonial society” – no one explained this to him because “the lines between white and black, between poor and rich were so clear”.

As a child, Cotto was extremely shy and unable to speak for himself in public or even at home.

Instead, like his father, who was also a poet and journalist, he found solace in words.

“I invent something, develop a relationship with the paper, and then behind the paper there is always someone I love, someone listening to me,” he told the BBC from his home in the Mozambican capital Maputo. Say: ‘You exist’.

Being of European descent, Couto was most easily identified with Mozambique’s black elite under Portuguese colonial rule – the “assimilators” – in the racist language of the time, those deemed “civilized” enough to become Portuguese citizens Connected.

The author considers himself lucky to have been able to play with the children of assimilationists and learn some of their language.

He said it helped him assimilate into the black majority.

“When I’m outside Mozambique, I remember that I’m white. Inside Mozambique, that really doesn’t happen,” he said.

As a child, however, he realized that his whiteness made him different.

“No one taught me about the injustice…the unfair society I lived in. I thought: ‘I can’t be me. I can’t be a happy person without fighting this. ,” he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Cotto was 10 years old, Mozambique’s struggle against Portuguese rule began.

The author remembers the night when, as a 17-year-old student who was writing poetry for an anti-colonial publication and keen to take part in the liberation struggle, he was summoned to meet Frelimo, the leader of the revolutionary movement.

Upon arriving at their residence, he found that he was the only white boy among 30 people.

The leader asked everyone in the room to describe what they had suffered and why they wanted to join Frelimo.

Cotto was the last to speak. As he listened to stories of poverty and deprivation, he realized he was the only privileged person in the room.

So, he made up a story about himself – otherwise he knew he had no chance of being drafted.

“But when it was my turn, I was speechless and overwhelmed with emotion,” he said.

What saved him was that Frelimo leaders had discovered his poetry and decided he could help their cause.

“The person presiding over the meeting asked me: ‘Are you the young man who wrote the poem in the newspaper?’ I said, ‘Yes, I am the author’. He said, “Well, you can come, you can be a part of us, because we need poetry,” Couto recalled.

After Mozambique gained independence from Portugal in 1975, Couto continued to work as a reporter for local media until the death of Mozambique’s first president Samora Machel in 1986.

“There is a rupture; I no longer believe what the liberators say,” he said.

After giving up his Frelimo membership, Couto studied biological sciences. Today, he remains an ecologist specializing in coastal areas.

He also started writing again.

“I started with poetry, then books, short stories and novels,” he said.

His first novel, “Sleepland”, was published in 1992.

This is a magical, realistic fantasy novel inspired by Mozambique’s post-independence civil war, taking readers through the brutal conflict that raged from 1977 to 1992, when the Resistance Movement (then a rebel movement backed by South Africa’s white minority regime ) had a fierce conflict with Western countries.

The book was an immediate success. In 2001, the book was judged as one of the 12 best African books of the 20th century at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair and has been translated into more than 33 languages.

Couto earned recognition for more novels and short stories about war and colonialism, the pain and suffering experienced by Mozambicans, and their resilience in hard times.

Other subjects he focused on included occult descriptions derived from witchcraft, religion, and folklore.

“I wanted a language that could translate the relationships and conversations between the different dimensions within Africa, the living and the dead, the visible and the invisible,” he told the BBC.

Couto is famous throughout the Portuguese-speaking world – in Angola, Cape Verde and São Tomé in Africa, as well as in Brazil and Portugal.

In 2013, he won the €100,000 ($109,000; £85,500) Camões Prize, the highest award for a Portuguese writer.

In 2014, he won the Neustadt Prize, which carries a prize of $50,000 (£39,000) and is considered the most prestigious literary award after the Nobel Prize.

When asked whether his work reflected the reality of modern Africa, Couto replied that this was impossible because the continent was divided and there were many different Africas.

“Due to the borders of colonial languages such as French, English and Portuguese, we did not know each other and did not publish our own writers on our continent,” he said.

“We have inherited some colonial buildings and have now ‘naturalized’ them, which are the so-called Anglophone countries, the so-called Francophone countries and the so-called Portuguese-speaking African countries,” he added.

Couto was due to attend a literary festival in Kenya last month, but unfortunately was forced to cancel the trip after mass protests broke out against President William Ruto. take action to raise taxes.

He hopes there will be other opportunities to strengthen ties with writers from other parts of Africa.

“We need to get rid of these barriers. We need to pay more attention to what we encounter as Africans and among Africans,” Couto said.

He lamented that African writers constantly looked to Europe and the United States as references, but were shy about celebrating their own diversity and relationships with gods and ancestors.

“In fact, we don’t even know what is being done in the arts and culture sector outside Mozambique. Our neighbors – South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania – we know nothing about them They don’t know anything about Mozambique,” Cotto said.

When asked what advice he would give to young writers starting out, he stressed the need to listen to others.

“Listening is not just about hearing sounds or looking at an iPhone or a gadget or a tablet. It’s more about being able to become someone else. It’s a migration, an invisible migration of becoming someone else,” Couto said.

“If you are moved by a character in a book, it’s because that character already lives inside you and you don’t even know it.”

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC