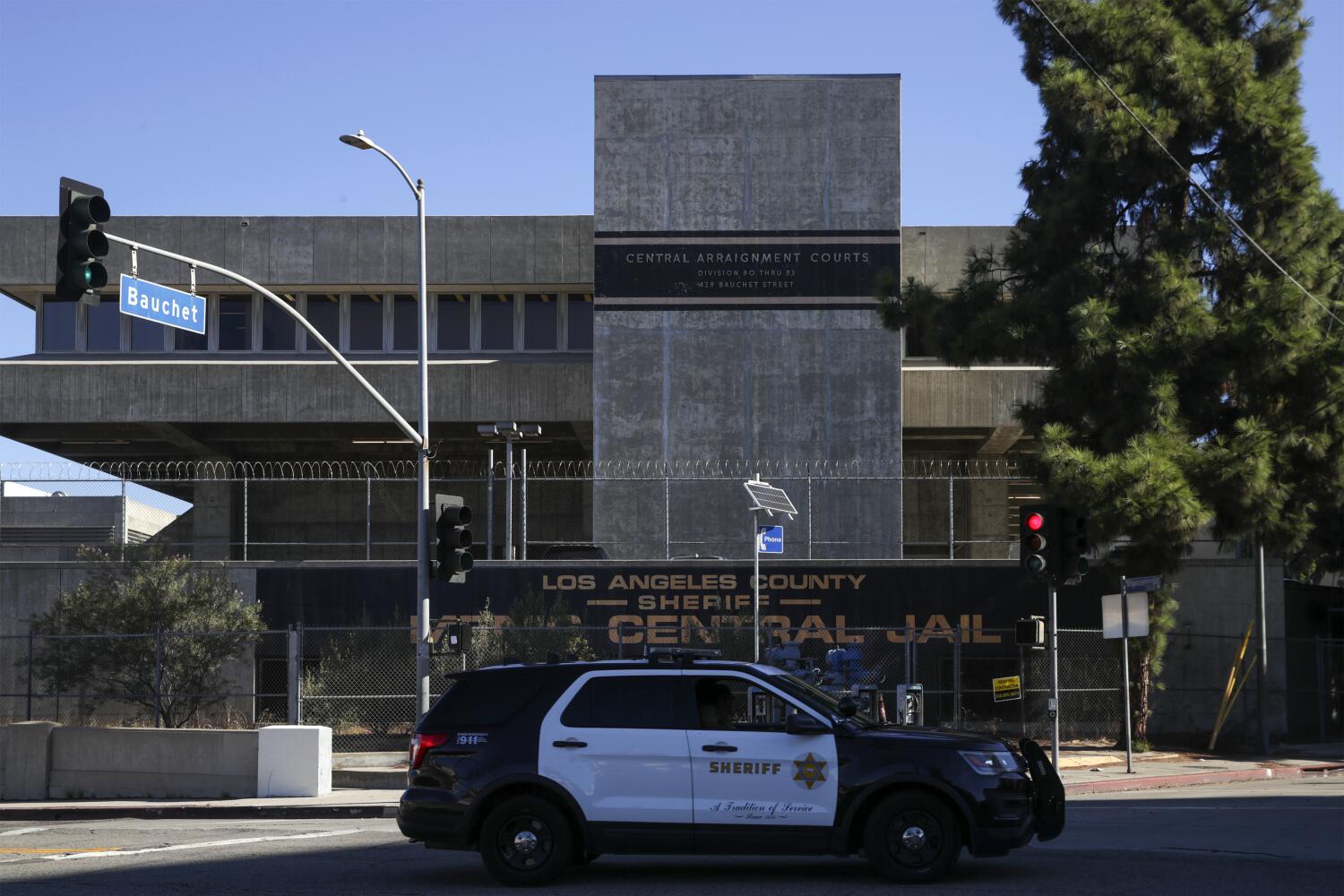

In the summer of 2019, justice reformers celebrated the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors’ repeal of a controversial $1.7 billion plan to replace the county’s oldest jail complex on Bauchet Street with a jail-like mental health facility. dungeon-like men’s central prison.

Fueled by a growing wave of jail reforms across the country, county leaders are determined to reduce jail populations by creating more alternatives to incarceration. The new goal is to close the Men’s Central Prison without building a replacement.

Five years later, the inmate population has dropped by about 5,000, but the Men’s Central Prison remains open. At the state level, the tide is turning, and voters will consider increasing penalties for: low-level theft and some drug crimesboth moves could lead to a surge in prison populations.

Against this backdrop, the board appears to be rethinking its strategy of not building new prisons.

“The pendulum has swung,” Supervisor Holly Mitchell said at Tuesday’s board meeting. “We’ve been saying: When are you closing the Men’s Central Jail? I think there needs to be a ‘what are we building or creating for this population that pretrial, diversion, community settings may not match.

Supervisors have been reluctant to consider the issue for the past five years, believing they could reduce the prison population to zero without building new facilities. But this week, the board publicly changed its tone after Sheriff Robert Luna and top jail officials told them that three-quarters of the county’s inmates faced charges that were too serious for a diversion program.

“I feel like we’re finally breaking through the conversation about why we need it and the rationale for why we need it, because the numbers don’t lie,” Superintendent Kathryn Barger said in an interview. “It has to be replaced.”

It’s unclear what the county might replace the jail with, or where the replacement jail will be located.

For some justice reformers, the recent change in tone is deeply disappointing.

Claire Simonich, deputy director of the nonprofit Vera California, questioned the department’s assertion that 75 percent of people in the jail cannot be transferred and that the new facility will solve problems currently plaguing the county’s jails.

“The Men’s Central Jail is dilapidated,” she said. “Building another prison will not address many of the issues and concerns we see at Men’s Central Prison, such as overdose deaths, inhumane treatment and inadequate mental health care.”

****

When the Men’s Central Jail opened five years ago, county leaders hoped the new capacity would end overcrowding and, in the process, improve deteriorating conditions at local jails. Instead, the facility drew a federal lawsuit that aggressively gang deputya scandal that swept the world Putting a former Sheriff in jail and an ongoing series of complaints from inmates, supervising officers and community members.

But county leaders’ response was hesitant. Three years after agreeing The county needs to build a new jail, Board of Directors 2018 Approved $2.2–billion plan This is accomplished by demolishing the existing facility and replacing it with a comprehensive correctional facility with a focus on rehabilitation.

The next year, the board changed course and approved a $1.7 billion project called mental health treatment center. The planned facility, approved in a 3-2 vote, will be overseen primarily by the Department of Health Services rather than the Sheriff’s Department, although a limited number of deputies will provide security.

‘It’s still a prison’ Soupadministrator Hilda Solis expressed her opposition to the plan at the time. “It’s still a wall. It’s still blocking people’s possibility of freedom, even recovery.

After a few months, the board abandoned the idea and started over, ultimately embracing a “care first, prison last” philosophy, with the goal of tearing down rotting prisons rather than building replacements. In 2021, the board approved an ambitious plan to reduce the inmate population by thousands so that the county could gradually close the facility before shutting it down entirely.

But the planned closing date – early 2023 – has passed, but the prison remains open. last year, The board of directors proposes a proposal Several recommendations to reduce the population were outlined, but no specific timeline for closures was provided.

Meanwhile, the situation is not improving. The county is still grappling with several long-running class-action lawsuits alleging abuse, poor conditions and inadequate mental health care at the jail. Prison death rates have risen sharply in recent years.

This year the county’s Sybil Brands Committee carried out inspections Already revealed Mold, rats, fires, broken toilets, sink drains filled with “little black bugs” and cells filled with feces. In May, two inspectors found a large group of prison guards watching “pornographic” videos instead of caring for an inmate who appeared to be suicidal. A crude cloth noose hung in his cell.

****

The tone of last week’s board meeting marked another change in direction for the county’s response.

Although the agenda called for a discussion of deteriorating conditions at the Men’s Central Jail, the conversation quickly turned to future plans for the facility.

Luna told supervisors he’s not sure the county can reduce the incarcerated population enough to close the Men’s Central Jail without replacing it, in part because officials estimate too many inmates face conditions too high for a diversion program. Violent or serious charges. Instead, he recommended setting up what he called a “care-first treatment campus,” which he said wouldn’t necessarily be run by sheriff’s deputies.

Barger, the only Republican on the board, seized on the suggestion as a way forward that could win over her more progressive peers.

“No matter what, the Men’s Central Jail needs to be demolished,” Barger told the meeting. “The fact that it doesn’t have to be a sheriff-run facility … maybe you just open a new door to finally doing something.”

Solis, who has historically been one of the board’s strongest opponents of new prisons, insisted that if another prison was built, it shouldn’t be in her district, which she said is already overrun with prison facilities, including the Men’s Central Jail and the Twin prisons.

“Obviously, I don’t want to see another prison built,” she said. “But if the board does this, it better not be in my district.”

Lindsey Horvath, the newest superintendent and one of the most progressive people on the board, is skeptical of the concept and told The Times she was “not familiar enough” with Luna’s vision to support the idea.

“I don’t know of any Sheriff’s Department that operates a facility that is not considered a jail,” she said in an interview.

****

The shift sparked a swift pushback from justice reform advocates, community activists and some prison oversight officials.

“I was completely blindsided by this,” said Anthony Arenas, an organizer with the Los Angeles Department of Justice, which has long opposed the construction of any new prisons. “This is just a new name for Men’s Central Prison – the ‘Care First Treatment Campus’ – which is even more surprising considering that this ‘nursing first, prison last’ thinking comes from community members advocating for the closure of Men’s Central Jail. disturbed.

At a meeting Thursday morning, members of the Sybil Brand Council, the county watchdog agency that inspects local jails, sharply criticized the idea of a “Care First” facility, saying Care First was in a historically troubled culture. “It’s not the same thing.”

“This is not just a facility issue,” Commissioner Haley Broad told The Times afterward, highlighting some examples of neglect and revengen by the jailer. “This is a cultural issue.”

and Peter EliasbergThe lead attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California rejected the central claim that sparked the discussion — that three-quarters of the prison population cannot be transferred or released before trial.

“No one should believe that this number is warranted,” he said. The county’s Office of Diversion and Reentry has successfully moved thousands of people, including some facing serious charges, out of jails, but never received enough fundingHe said.

And the most recent one UCLA study finds Los Angeles courts Bail amounts are set well above the state average. Eliasberg said reducing bail alone could help reduce the jail population.

He went on to say that the suggestion that most prisons cannot be transferred is “ridiculous,” adding: “If the board were to consider making policy based on this statement, one thing my father would say is – ‘You tend to move on a fragile spring’. on-chip’ – I think that’s totally appropriate here.