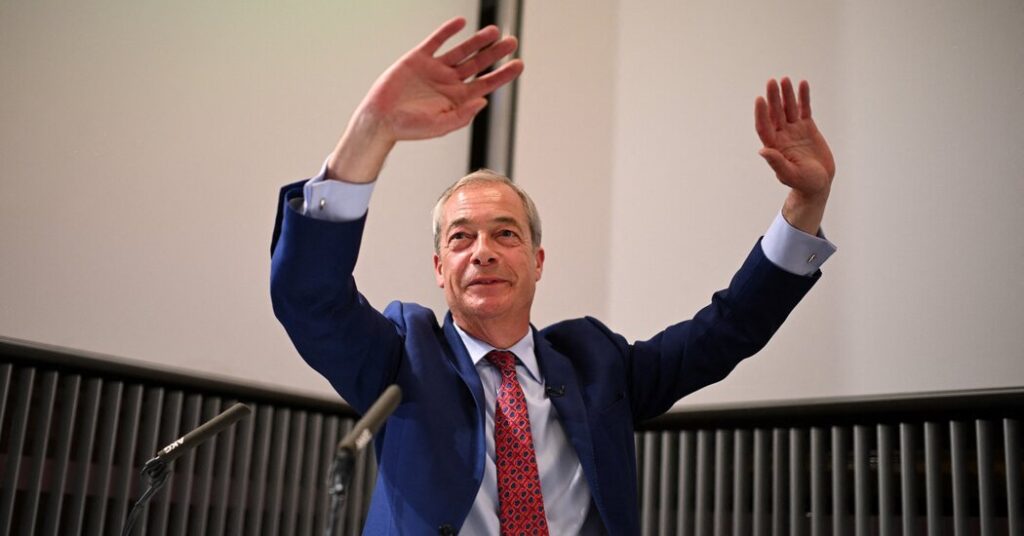

At first, Nigel Farage remained calm. When protesters disrupted Mr Farage’s election victory speech, Mr Farage, a veteran British political subversive, anti-immigrant and ally of former President Donald J. Trump, ignored them.

But as the chaos continued at a media conference on Friday, Mr Farage struck back, shouting “boring!” over his critics. into the microphone no less than nine times.

However, with Farage at his side, things are less boring, as Britain’s centre-right Conservative Party has just discovered to its cost.

The Conservatives lost power after Labour’s landslide victory and collapsed 14 years later, suffering their worst defeat in modern history, a stunning defeat that left the party’s remnants in disarray. By contrast, Farage’s small rebel party, Reform Britain, is well on its way and has elevated him to a central role in determining the future of the British political right – and perhaps the country’s overall direction.

His emergence on the political stage, along with his harsh anti-immigration rhetoric, could have a crucial impact on the trajectory of the Conservative Party, Conservative leader and former prime minister Rishi Sunak said on Friday , he will step down once he is succeeded.

Not only did reformist candidates win five parliamentary seats – including Mr Farage’s for the first time in eight attempts – but the party also received around 14% of the national vote. By this measure, the Reform Party is the third most successful party in the UK and can be compared with France’s emerging right-wing National Rally party.

Matthew Goodwin, professor of political science at the University of Kent, said of Britain’s new Labor prime minister: “There are foundations for reform that can pose a serious challenge not only to the Conservative Party but also to Keir Starmer and the Labor Party.” “The problem It’s: Can Nigel Farage build an organization, a party structure and a professional operation that achieves what he historically struggled to achieve with his predecessors.”

Farage, 60, is a bombastic, combative and charismatic figure who has long infuriated the Conservative Party, which he quit in 1992. and ridicule – including once when former leader David Cameron said supporters of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), which Farage was leading at the time, were “fruitcakes, lunatics and secretly racist”.

But it was pressure from UKIP that forced Cameron to commit to a referendum on Brexit, which he failed in 2016, ending his tenure in Downing Street.

Mr Farage recently retired from politics and did not decide to run in the general election until 11 o’clock. But his influence has been huge, and his campaign against immigration has struck a nerve with the Conservative Party, whose government has seen legal immigration triple since Britain left the EU.

“He’s very approachable,” said Tim Bell, a political science professor at Queen Mary University of London. “He is a consummate political communicator with a charisma that many mainstream politicians cannot match because they have to deal with real issues, not made-up ones.”

Some right-wing Conservatives want to invite Mr Farage back to their party. Others worry he will alienate moderate voters.

He suggested that the Reform Party could replace the Conservatives and that he could even take over the party.

But if he doesn’t do anything, he’ll have proven the threat he poses.

In 2019, Farage’s then-led Brexit Party chose not to run candidates against many Conservative MPs, avoiding the risk of splitting the right-wing vote and helping former Prime Minister Boris Johnson secure a landslide victory.

Mr Farage’s new party campaigned across the country last week, with the Conservatives losing dozens of seats. Professor Goodwin calculated that in about 180 constituencies the Reform vote was higher than the Conservative defeat rate.

“They have problems on multiple fronts,” Professor Goodwin said, noting that the Conservatives lost votes to Labor and the centrist Lib Dems, “but Farage is by far the biggest problem facing the Conservatives.”

The party now faces a key decision about who will lead them and what type of politics will be adopted.

One faction hopes to move to the right to counter the reformists, who in general elections have eaten into the Conservative vote in pro-Brexit areas of northern and central England, often paving the way for Labour’s victory. Professor Goodwin believes that after Brexit, support for the Conservative Party is now more concentrated among voters who are more socially conservative and hostile to Europe.

But the Conservatives also lost to Labor and the smaller pro-European centrist Liberal Democrats, which won 72 seats by campaigning in the Conservative heartland of the more socially liberal south of England.

“The Conservatives lost this election on two fronts, but they seem to care more about one of them,” Professor Bell said. He said the conservatives seemed to blame reformists for their defeat, ignoring the fact that their right-wing policies, promising to counter the Farage threat, had cost them votes in the political centre.

The ultimate choice of who becomes leader of the Conservative Party is made by party members, who tend to be older and more right-wing than the average Briton. Professor Bell said: “It is difficult to imagine that a party whose members are ideologically and demographically unrepresentative of the average electorate could elect a more moderate Conservative Party.”

Compounding matters for moderates, senior cabinet minister Penny Mordaunt lost her seat at the election, dropping out of the race and reducing the pool of credible candidates.

That bolsters the prospects of right-wing contenders including former home secretary Priti Patel. Kemi Badenoch, the former business and trade minister; and Suella Braverman, another former home secretary. Some of her comments echoed those of Mr Farage, who described the arrival of asylum seekers by boat on Britain’s south coast as an “invasion”.

Some Conservatives hope that the scandal-plagued but charismatic Johnson – who did not contest the election – will finally return to confront the threat posed by the reforms.

The top contender to invite Mr Farage to join the Conservative ranks is Ms Braverman, but analysts see her as unlikely to become leader. Most of her rivals are wary of Mr Farage, believing he might be able to eclipse them.

“I don’t think you’re going to see Farage involved in the Conservative Party for a long time; he just doesn’t believe in the Conservative Party,” Professor Goodwin said.

Speaking before the election, Farage told the New York Times that he “really doesn’t see the Conservative Party as we know it being fit for purpose in any way: Brexit highlights the divide between two very clear factions” Asked if he could rejoin, Mr Farage said: “That won’t happen. “

Assuming this is correct, much will depend on his ability to transform upstart Reform Britain with only skeletal infrastructure into a force capable of mounting a challenge at the next general election, which must be held before 2029.

Whether he can do that is far from certain. The Reform Party performed significantly worse than UKIP in the municipal elections, suggesting an incomplete activist base and demonstrating that it is what Professor Bell calls “an AstroTurf party, not a grassroots party”.

Racist and homophobic comments by some Reform activists and candidates have sparked outrage and highlighted the difficulties the Reform faction faces in vetting key supporters.

And Mr Farage, a reformist leader, has struggled to delegate or share the spotlight. He was also known for arguing with colleagues.

Professor Bell said Mr Farage “clearly does have difficulty tolerating any form of opposition or alternative direction for the party from others”.

“He’s the ultimate one-man band.”