Around 2 p.m. on a Thursday in May, Mitch Carroll pulled up to a teal-trimmed apartment building in Madison County, Indiana.

He was wearing jeans, a T-shirt and plain white sneakers. But to the middle-aged woman who opened the door, it was obvious he was enforcing the law. He had a badge on his waist and a Glock 9mm pistol.

“Hi, are you Sharon?” Carol asked.

“Yes,” the woman replied.

“Sharon, my name is Mitch Carroll. I work for the Madison County Prosecutor’s Office,” he said. “Take a deep breath. You’re not in trouble.

Carroll is a retired police officer who investigates truancy incidents. He tries not to alarm the families he visits because he wants to build relationships with them — relationships he hopes will help ensure students in his county receive an education.

School absenteeism has surged during the pandemic and remains high. About a quarter of U.S. students will be chronically absent during the 2022-23 school year, according to data compiled by the American Enterprise Institute. This means that they were absent for 10% or more of the school year, with or without reason. These missed days can hamper learning: Younger students are less likely to read on grade, making them more likely to drop out of high school later in life.

When students miss a lot of class No An excuse, this is called truancy. Every state has truancy policies, many of which make it illegal to not attend school.

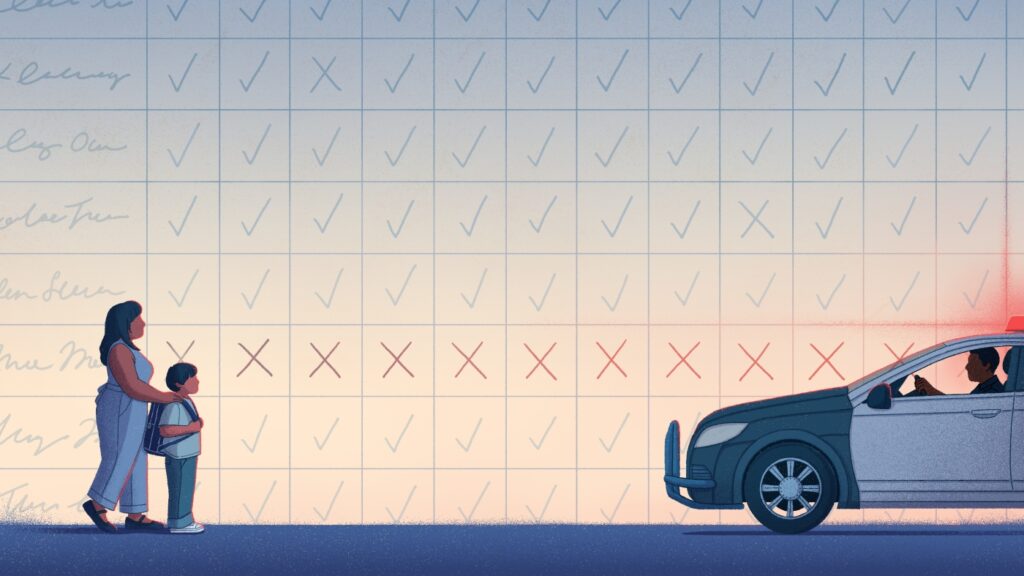

Consequences vary by state and jurisdiction. In some truancy cases, courts may jail parents or detain students. More commonly, families face court oversight of school attendance, required meetings, fees and home visits from officials like Carroll.

Make sure families have plans for schooling

NPR spoke with Carroll as he drove around Madison County to visit family. He stopped by Sharon’s house because her 14-year-old grandson had been absent about 30 times. We will only identify Sharon by her first name, not her grandson, because this story involves sensitive information about him.

When Sharon walked out to the porch, she called her grandson, who was in middle school. She said the reason he missed so many days was because he was anxious.

“It’s not that he doesn’t want to go to school,” Sharon told NPR during the visit. “He’ll be dressed and ready to go. But when he’s ready to go, he gets really excited.

Sharon said she had medical notes for his multiple absences and asked his doctor for help. But he still struggled. She recently withdrew her grandson from public school. She plans to homeschool him, hoping it will reduce his stress.

“Sharon, my job here is to make sure you know; I just don’t want him to go anywhere,” Carol said. “Because you know at some point, you’re probably going to get word of juvenile probation.”

Carroll left saying he was optimistic about his visit with Sharon. Sometimes caregivers say they homeschool without a plan to educate their children, Carroll said. But Sharon is working with her niece, who is homeschooling her own children. “This is a win.”

Carol was friendly and calm during her visit. Still, a knock on the door from law enforcement can make guardians nervous. It’s for Sharon.

“I recognized him as soon as he showed up,” she told NPR. “I thought, ‘Oh, shoot. I’m going to the police station. They’re booking me. He’s about to enter his teenage years.’

When NPR called Sharon in July, she said she planned to send her grandson back to school. His doctor put him on medication, and she believes he’ll be better this year.

Are these interventions effective?

There is no simple explanation for why school absenteeism continues to surge as the pandemic recedes. Educators told NPR that students often stay home with relatively mild illnesses. Unstable housing, unreliable transportation, and mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety may also play a role. Some students skip school because they don’t want to go.

In many communities, the issue seems intractable.

“Schools are overwhelmed,” said Nina Solomon of the Council of State Governments Justice Center. Solomon explained that communities don’t always have the resources, such as behavioral health supports, to help families with underlying issues. “So we’re seeing a lot of states trying to use the court system more because they feel like that’s the only tool they have at their disposal.”

Clea McNeely, a professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, said there isn’t much high-quality research on court-based truancy interventions. McNeely is one of a handful of researchers have Saw these programs.

She studied intervention models operating at the county attorney’s office and local school district in Ramsey County, Minnesota, more than a decade ago. If a student continues to miss school, families must sign a contract that includes a plan to improve attendance. For example, parents may try to change their work schedules. Eventually, if attendance still doesn’t improve, the case may go to court.

McNeely’s findings: There was no change in attendance among elementary school students, while middle school and high school students were actually absent at slightly more rates than students in neighboring counties without similar programs.

“It saddens me to deliver this news. I love this project,” McNeely said. good.

McNeely said her findings targeted practices in Ramsey County in the 2000s. She warned that projections of court intervention can vary widely and cautioned against drawing broad conclusions based on her research.

“You can’t say it works or it doesn’t work,” McNeely explained. “You have to pay attention to its structure.”

For McNeely, one of the main problems with court interventions is that they cost money that could be spent on other, more effective strategies. She cited a home visiting model in Connecticut that early evidence shows improves attendance.

But in Connecticut, law enforcement isn’t visiting homes; rather, educators and community members are visiting.

Indiana prosecutors say they’re making a difference

Last school year in Madison County, Indiana, where Mitch Carroll works, schools referred more than 600 students and guardians to the prosecutor’s office for violating state truancy laws. Many of those cases ended with warning letters, the prosecutor’s office said. But the office filed truancy charges against about 40 students and charged more than 120 parents and guardians with violating the state’s compulsory education law.

Chief Deputy Prosecutor Andrew Hanna said adults “will actually not face criminal penalties as long as we keep their children in school.” That’s the goal. This is not about getting people criminally charged. It’s not about making their lives more difficult than they already are.

Researchers may be skeptical that the justice system can help, but Hanna and his boss — Attorney Rodney Cummings — believe their office should enforce the state’s school attendance laws and use the courts to try to ensure children and youth education.

“We allege a case in which parents grossly failed to fulfill their most basic responsibilities to their children and ensure they received an education,” Hanna said.

The Madison County Prosecutor’s Office doesn’t yet have data on whether its enforcement efforts are helping improve attendance because its focus on truancy is relatively new. Staff there describe their efforts as a work in progress, saying they are working to improve as they learn more.

Investigator Mitch Carroll maintains an affable and positive attitude while visiting family members. But sometimes a visit does feel like a failure.

“Usually if that’s the case – it’s because the parents are apathetic or just uninvolved,” he said. “I’ve encountered a lot of situations where parents weren’t interested in being parents.”

‘This is not a perfect scenario’

On the day NPR visited with Carroll, he knocked on nearly a dozen doors. Most families answered.

Carroll learned that a high school student who was attending virtual school for only about 20 minutes a day had recently given birth.

He spoke with the mother of a middle school student who skipped school to go to a friend’s house because he was being bullied.

He also met a 16-year-old student who had been working shifts at Walmart without online classes.

Around four in the afternoon, Carol parked her car in front of a nondescript house on a quiet suburban street.

There are many elementary school students in the family, and each of them has been absent without excuse more than 20 times. A woman opened the door and invited Carol inside.

“Are you familiar – I don’t want to be condescending to you, you sound like a smart girl,” Carol said, “but do you understand the difference between an excused absence and an unexcused absence?”

“Yeah, it was definitely because I forgot to turn in their paper,” J explained. She said her children were absent a lot because they were sick. Two of her children suffer from asthma, and the family has contracted the flu twice in recent months.

“If these three kids got the flu, I wouldn’t send the other kids,” she said, “because I feel like it would make everyone else sick.”

If J could get a doctor’s note, the days her child was sick would not be counted as truant under Indiana law.

But no matter why students miss school, missing school is bad for children in the long run. It lowers their reading and math scores and lowers their chances of graduating from high school.

After Carroll left J’s home, he told NPR that he planned to contact the school. The children have been absent for many days and “it’s not a perfect situation,” he said. But “the house looks clean. The kids are clean. They’re well behaved.”

One more stop, and then Carol returned to the prosecutor’s office.

His mission for the day was complete. But he will continue to visit into the summer. He hopes it will make a difference and maybe be enough to get students back in school.

Edited by Nicole Cohen

Sound Story produced by Janet Woojeong Lee