AFP

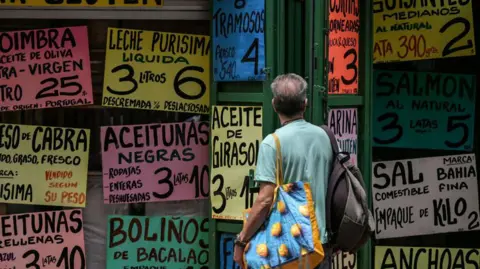

AFPVenezuela’s battered economy is one of the key battlegrounds in Sunday’s presidential election, with President Nicolás Maduro hoping to convince voters that the country has turned a corner after years of conflict.

The outlook is slightly more positive due to his recent efforts to lower the cost of living. In February this year, Venezuela finally said goodbye to rampant hyperinflation, with price increases in 2019 reaching a peak of more than 400,000 per year.

Annual inflation is now more manageable, but is still high around 50%.

Maduro has been keen to take credit for the defeat, saying it showed he had “the right policies”.

Unfortunately, however, these policies have done little to address the economy’s underlying structural problems, principally its historical dependence on oil, to the detriment of other sectors.

As the Council on Foreign Relations think tank puts it, “Oil has taken Venezuela through an exciting but dangerous journey of boom and bust since its discovery in the country in the 1920s.”

Opponents of President Maduro are now pinning their hopes for economic recovery on a change of leadership and a new beginning under his election rival Edmundo Gonzalez.

“An opposition victory will lead to a reopening of Venezuela’s trade and financial relations with the rest of the world,” said Jason Tuvey, deputy chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics.

It also means the end of U.S. economic sanctions imposed after Maduro’s victory in the 2018 presidential election, which was widely seen as neither free nor fair.

These factors make it difficult for state oil company PDVSA to sell its crude oil internationally, forcing it to trade on the black market at deep discounts.

But Tuvey warned that reversing the economic collapse of the past decade would be a difficult task, given the huge investment required to boost oil production and the impending peak of oil demand.

“Venezuela’s economy will never get back to where it was 15 to 20 years ago,” he told the BBC. “In general, this will start from the beginning.”

AFP

AFPVenezuela’s 25-year-old Bolivarian Revolution (the name the late President Hugo Chavez gave his political movement) promised many things but failed to deliver what the country arguably needed most: a broad-based economy .

Rather than diversifying away from the oil industry, the Chávez and Maduro governments have doubled down on investments in Venezuela’s mineral wealth.

They are indifferent to the future and view PDVSA as a cash cow, leeching its funds to fund social spending on housing, health care and transportation.

But at the same time, they have neglected investments to maintain oil production levels, which have fallen sharply in recent years — partly but not entirely due to U.S. sanctions.

These problems are already obvious When President Chávez died in 2013but things got worse under the watch of his successors.

“Under Chávez, Venezuela was able to ride the coattails of the oil boom until the global financial crisis hit,” Mr Tuve said.

“Fifteen to twenty years ago, Venezuela was a major oil producer. It used to produce three and a half million barrels a day, along with some of the smaller Gulf states.

“The oil industry is now completely hollowed out, producing less than 1 million barrels a day.”

GDP has fallen rapidly, down 70% since 2013.

Economic hardship has hit the Venezuelan people hard, with more than 7.7 million people, about a quarter of the population, fleeing their homes in search of a better life.

But for those left behind, there are already signs of improvement. While the bolivar remains the official currency, informal dollarization has occurred, with the U.S. dollar increasingly becoming the payment method of choice in retail transactions—at least for those with access to U.S. dollars.

This stabilizes the economy but comes with social costs.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesResidents of the capital, Caracas, now find themselves affected by a two-tiered economy. While dollars fuel a spending boom in high-end stores and restaurants, those who pay in bolivars feel increasingly left out.

A symbolic event that highlights these changes was the recent appearance of Colombian reggaeton superstar Karol G in Caracas as part of her current world tour.

Few major artists perform in Venezuela these days, but she had no problem getting tickets for two nights at the 50,000-capacity Monument Stadium in March, although tickets range from $30 to $500 (£23 to £390).

Meanwhile, about 65% of Venezuelans earn less than $100 a month, according to Caracas consulting firm Ecoanalítica, and only eight to nine million of the country’s 28 million people can be considered consumers with actual purchasing power.

“Those close to the regime or PDVSA have been virtually unaffected by all this,” Mr Tuve said.

AFP

AFPIn addition to the need to improve living standards and reduce inequality, another major economic challenge facing Venezuela is how to deal with its massive debt.

The country’s debt to creditors and other foreign creditors is estimated at $150 billion. has been in partial default since 2017 despite Mr Maduro’s repeated promises Negotiate restructuringhas not happened yet.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that some of the bonds were issued by PDVSA using the company’s U.S. refinery Citgo as collateral. Therefore, bondholders were able to resolve the issue through New York courts.

Bruno Gennari, emerging markets strategist at investment bank KNG Securities, told the BBC that Venezuela was in a “crisis of legitimacy” because the United States did not recognize Maduro as president after the 2018 election.

That means whoever wins Sunday’s election must be accepted by Washington if a U.S.-sanctioned debt restructuring is to take place.

Mr Gennery did not rule out that the United States “could turn a blind eye” if Mr Maduro won the election under questionable circumstances, but he considered that unlikely.

“This election will have considerable consequences for Venezuela’s future. If the restructuring can go ahead, we may see the beginning of a very complex recovery process,” Mr Gennary said.

Venezuela, once the richest country in South America, may now be able to regain stability — but whatever happens, its economic glory days are behind it.