The 4.9-magnitude earthquake that struck Southern California on Monday raised some classic questions: Why did some people feel the earthquake lasted for a long time, while others felt it lasted only a short time, and some didn’t feel it at all?

Not surprisingly, the strongest and longest shaking was felt by people at the epicenter near Barstow.

But in the Los Angeles Basin, some residents felt nothing at all, while others reported shaking for up to 15 seconds.

In Pasadena, about 95 miles southwest of the epicenter, U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Morgan Page felt nothing as she walked on the first floor, but her colleague sitting in a second-floor chair felt shaking for several seconds.

Reporters on the sixth and seventh floors of The Times’ El Segundo headquarters next to Los Angeles International Airport, about 115 miles southwest of the epicenter, felt relatively mild shaking for 15 to 20 seconds.

The ground you walk on is important

Page said that for people at the epicenter of an earthquake, the shaking seems to last longer because the ground motion you feel is weaker, while the motion generated by the earthquake is stronger. In contrast, people farther away may feel only some major ground movements.

The type of rock and soil under your feet is also important.

If you’re in a basin — whether it’s the Mojave Basin or the Los Angeles Basin — you have “basically more wobbly sediments” beneath you, Page said, which creates “longer shaking, but also Intensify the shaking.”

The Los Angeles Basin is a 6-mile-deep, bathtub-shaped hole in the underlying bedrock filled with soft sand and gravel that eroded from the mountains, creating the flat land where millions of people in Southern California live. When seismic energy is transmitted into these sedimentary basins, it amplifies the intensity of the shaking—perhaps ten times greater than it would be in bedrock—and also causes the shaking to resonate like a bowl of jelly, extending its duration.

“The waves get trapped in the basin, which just makes the shaking last longer. But you also amplify it, so you feel the wave’s amplitude higher, and therefore the shaking more strongly, which you wouldn’t feel if there wasn’t amplification. . So both contributed to that duration,” Page said.

People who sit are more likely to experience tremors than those who are walking or moving. “It makes a big difference if you’re doing something versus if you’re just sitting still,” she said.

The higher the floor, the greater the vibration.

Your height in the building is also important.

People at the top felt the shock more strongly than those at the bottom, Page said.

Imagine if you had a table with a spring on top and a weight on top – like an inverted pendulum. “If you shake the table, the top of the spring will shake more than the bottom,” Page said, explaining how people on the top floors of the same building would feel more motion than people on the bottom.

“On the ground floor, you’re connected to the ground. On the top floor, you rock on this semi-flexible, semi-rigid structure,” Page said.

Lessons from Ridgecrest

The difference in shaking was evident in the 2019 Ridgecrest 7.1 earthquake, whose epicenter was 125 miles northeast of downtown Los Angeles

During that quake, people sitting in the lobby of a downtown skyscraper might have felt a sway of light for a few seconds. But on the 50th floor, the experience was terrifying, with the floor’s sensors swaying back and forth a foot in each direction for two to three minutes.

On the 48th floor of another downtown building, a woman became dizzy and her husband became motion sick after swaying for several minutes.

Monica Kohler, a research professor of civil engineering at the California Institute of Technology, said in 2019 that during some earthquakes, “when you’re in a tall building, you get seasick.”

Even during Monday’s 1 pm quake, people throughout central Los Angeles reported varying experiences of shaking. In Silver Lake, Lucas, a 6-year-old tuxedo cat, was rocking to sleep when his owner on the third floor of an apartment building felt rolling motion that lasted four to six seconds.

In the Los Feliz-East Hollywood area, a person sitting at a table felt two waves of shaking – the first lasting about three to four seconds before the shaking subsided, and then a second wave that shook the walls for five to six seconds. Second. But the other people next to me didn’t feel anything.

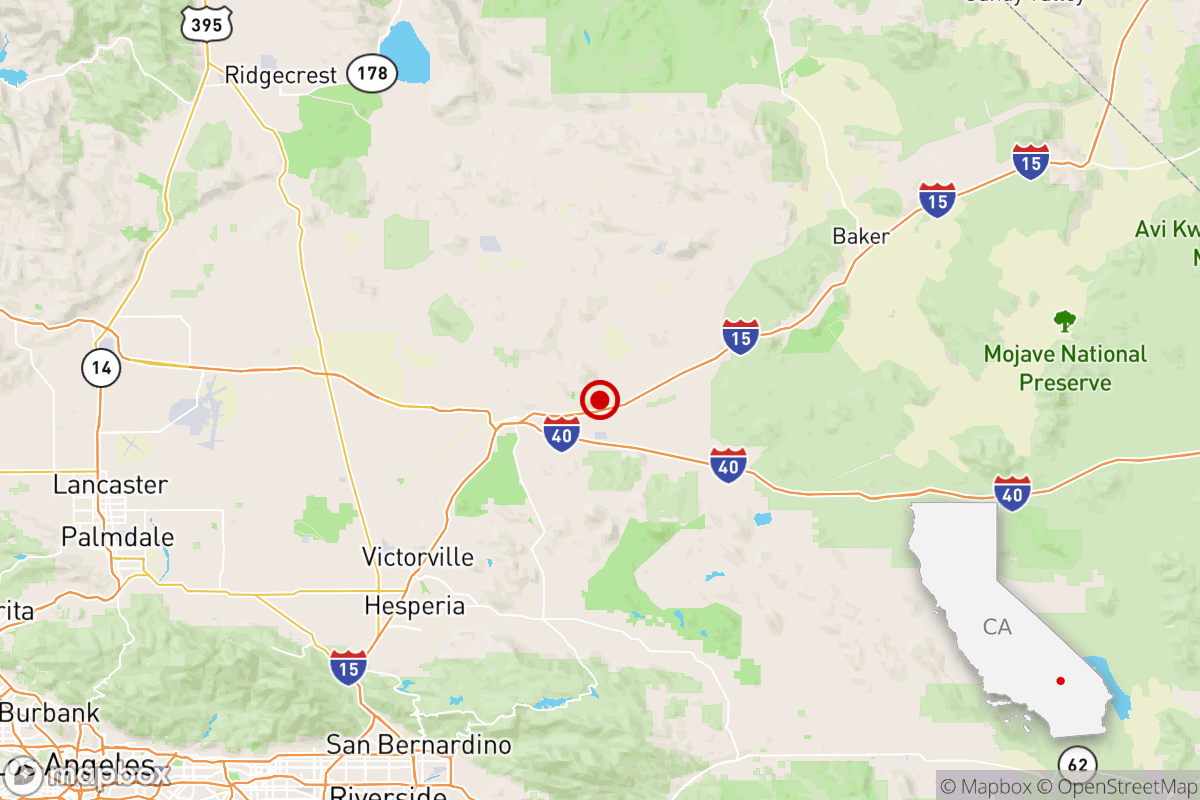

The epicenter of Monday’s 4.9-magnitude earthquake was in California’s Mojave Desert, about halfway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

P wave and S wave

Los Angeles may have been too far away from Monday’s epicenter for anyone to feel the quake’s “P” waves — the first type of shockwave produced by an earthquake, in which rocks vibrate in the direction of the moving waves. But Page said people in Los Angeles may have felt “S” waves, in which bedrock vibrates perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation.

Page said the last bits of tremors felt here were likely due to longer-period surface waves that emerged later. Surface waves are the longest lasting waves that enter and travel along the Earth’s surface, arriving even after S waves.

Surface waves “often feel like you’re on a boat. They’re almost a wave that makes you motion sick, rather than the nerve-wracking P and S waves you got before,” Page said.

Times staff writers Jim Buzinski, Brittny Mejia, Joel Rubin, Nathan Solis and Terry Tang contributed to this report.